William Bell (photographer)

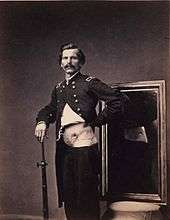

William H. Bell (1830 – January 28, 1910) was an English-born American photographer, active primarily in the latter half of the 19th century. He is best remembered for his photographs documenting war-time diseases and combat injuries, many of which were published in the medical book, Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, as well as for his photographs of western landscapes taken as part of the Wheeler expedition in 1872. In his later years, he wrote articles on the dry plate process and other techniques for various photography journals.

- Not to be confused with William Abraham Bell, a contemporary who also worked as a photographer.

William H. Bell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1830 |

| Died | January 28, 1910 (aged 79–80) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Relatives | William H. Rau (son-in-law) |

Life

Bell was born in Liverpool, England, in 1830, but immigrated to the United States with his parents as a young child. After his parents were killed in a cholera epidemic, he was raised by a Quaker family in Abington, Pennsylvania, outside of Philadelphia.[2] In 1846, at the outbreak of the Mexican–American War, Bell traveled to Louisiana and joined the 6th Infantry.[3]

After the end of the war in 1848, Bell returned to Philadelphia, and joined the daguerreotype studio of his brother-in-law, John Keenan.[4] In 1852, he opened his own studio on Chestnut Street, and would operate or co-manage a photographic studio in downtown Philadelphia for much of the remainder of his life. In 1862, following the outbreak of the Civil War, Bell enlisted in the First Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers,[2] and saw action the battles of Antietam and Gettysburg.[3]

After the war, Bell joined the Army Medical Museum (now the National Museum of Health and Medicine) in Washington, D.C., as its chief photographer. He spent much of 1865 making photographs of soldiers with various diseases, wounds, and amputations, many of which were published in the book, Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. He also took portraits of dignitaries visiting the museum, and photographed Civil War battlefields. In 1867, he returned to Philadelphia, where he purchased the studio of James McClees.[4]

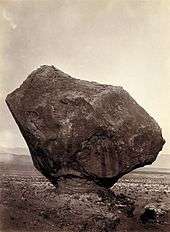

In 1872, Bell joined George Wheeler's survey expedition, which was tasked with surveying American lands west of the 100th meridian, as a replacement for photographer Timothy H. O'Sullivan. As part of the expedition, he captured numerous large format and stereographic landscapes of relatively unexplored areas of the Colorado River basin in Utah and Arizona. While on the expedition, he experimented with the dry plate process, for which he would eventually become an expert.[3]

After the expedition, Bell returned to his studio in Philadelphia, and exhibited his work at the city's 1876 Centennial Exposition. Following the exposition, he sold his Chestnut Street studio to his son-in-law, William H. Rau. In 1882, Bell was hired by the U.S. Navy as a photographer for its Transit of Venus expedition. En route to Patagonia, where the Transit was observed, Bell captured a series of photographs of the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden in Brazil.

Bell spent most of his later years doing studio work and writing technical articles for journals such as Photographic Mosaics and the Philadelphia Photographer, though he traveled to Europe in 1892 to photograph paintings for the Columbia World's Fair. He died at his home on Boston Avenue in Philadelphia on January 28, 1910, after a long illness.[3]

Along with his son-in-law, William Rau, Bell's son, Sargent, and daughter, Louisa, were avid photographers.[4][3] His son, Henry, was an engraver.[3]

Works

His career spanning six decades, Bell worked in nearly every major early photographic process, including daguerreotype, collodion processes, albumen prints, stereo cards, and early film. He was considered a pioneer of the dry plate and lantern slide processes, and experimented with night photography, using magnesium wire for lighting.[2] He wrote technical articles on topics such as gelatine emulsions,[5] the use of pyrogallic acid to recover gold from waste solutions,[6] and the development of isochromatic plates.[7]

For his Wheeler Survey photographs, Bell used two cameras – an 11-inch (280 mm) × 8-inch (200 mm) for large prints, and an 8-inch (200 mm) × 5-inch (130 mm) for stereo cards. He used both wet and dry collodion processes on this expedition, and his photographs are characterized by dark foregrounds with elements becoming increasingly lighter in tone as distance increases. Landmarks photographed by Bell include the Grand Canyon, the Marble Canyon, the Paria River, Mount Nebo, and the early Mormon settlement of Mona, Utah.[8]

Bell's work was exhibited at the Vienna Universal Exposition and the Louisville Industrial Exposition in 1873, and at the Centennial Exposition in 1876. His photographs are now included in the collections of the Smithsonian American Art Museum,[9] the National Museum of Health and Medicine,[10] the Library of Congress' Prints and Photographs Division, and the George Eastman House.[11]

Gallery

.jpg) Chocolate Butte near mouth of the Paria River, Arizona

Chocolate Butte near mouth of the Paria River, Arizona Kanab Canyon in Arizona

Kanab Canyon in Arizona.jpg) Taylor's Creek Canyon, Utah

Taylor's Creek Canyon, Utah.jpg) Salt Creek Canyon, Utah

Salt Creek Canyon, Utah

References

- William Bell obituary, Philadelphia Inquirer, 30 January 1910. Retrieved from the National Museum of Health and Medicine online database, 4 April 2012.

- William Bell obituary, Philadelphia Public Ledger, 30 January 1910. Retrieved from the National Museum of Health and Medicine online database, 4 April 2012.

- Barbara Mayo Wells, "William W. Bell, 1830 – 1910," Luminous-Lint.com. Retrieved: 5 April 2012.

- "The Photographic Society of Philadelphia," American Journal of Photography, Vol. 12 (1891), p. 233.

- William Bell, "Use of Pyrogallic Acid in Recovering Waste Gold Solutions," The Photographer's Friend, Vol. 1, No. 1 (January 1871), p. 17.

- William Bell, "Improved Developer and Isochromatic Plates," Photographic Mosaics (1896), p. 125.

- U.S. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division – online search results for William Bell (1830–1910). Accessed: 5 April 2012.

- "William Bell". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- D'Souza, Rudolf J.; Kathleen Stocker (2008). "Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine: Finding Aid for the William Bell Collection". National Museum of Health and Medicine. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- "George Eastman House Still Photograph Archive Full Catalog Record: William Bell". George Eastman House. 2001. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William Bell (photographer). |

- Photographic Archive for William Bell at George Eastman House

- William H. Bell at the Getty Museum