William Adam (minister)

William Adam (1 November 1796 – 19 February 1881) was a British Baptist minister, missionary, abolitionist and Harvard professor.

Prof. William Adam | |

|---|---|

... at the back with the ladies | |

| Born | 1 November 1796 |

| Died | 19 February 1881 |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Baptist College in Bristol, University of Glasgow |

| Occupation | missionary and minister |

| Title | Professor of Harvard |

Scotland and India

Adam was born in Dunfermline in Scotland, and it was after being inspired by the churchman Thomas Chalmers that he decided to go to India. He arranged to be educated at the Baptist College in Bristol and to the University of Glasgow. Adam volunteered to become a missionary and by 1818 he was working hard north of Calcutta trying to master Sanskrit and Bengali. Having learned these he was engaged in creating a translation of the new testament in Bengali. He worked with Ram Mohan Roy and he supported Roy's insight into the translation.[1]

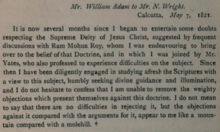

Later after many discussions on Christianity and Indian thoughts on God, he found himself unable to resolve the doubts on Jesus Doctrines and logically felt defeated. (The life and letters of Raja Rammohun Roy by Collet, Sophia Dobson, 1822-1894, Page-68)

Adam lost interest in the Baptist Mission, but not India, and with Roy and a mix of locals and Europeans formed the Calcutta Unitarian Society. The society ended in an unusual way when the Hindu membership became interested in the emerging ideas of Brahmo Somaj. In 1830,Adams was appointed by the colonial government of Bengal to carry out a census and analysis of native education in Bengal.[2]

America and Britain

With the help of American friends, Adam sent his family and left himself years later in 1838. There he met abolitionists and his background qualified him to be sent by the Americans as their representative to the anti-slavery meeting in London of the British India Society.[1]

Boston East Indian merchants were so impressed by his linguistic skills that they arranged for his to be made a Professor of Oriental Linguistics at Harvard University,[3] but by 1840 he was publishing public letters to Thomas Fowell Buxton warning of British complacency of assuming that because the West Indies no longer had slavery it did not mean that the British Empire had renounced slavery whilst India was unchanged.[4]

- ^ The Anti-Slavery Society Convention, 1840, Benjamin Robert Haydon, 1841, National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG599, Given by British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society in 1880

In 1840, Adam was sent with a large number of other Americans to the World's Anti-Slavery Convention in London, where he presented a paper about India. After the convention was completed the more notable people were recorded in a large painting for the Anti-Slavery Society (that painting is now in the National Portrait Gallery). Adam managed to squeeze into the very top right of the painting, but this was his position. Adam had arrived late due to a shipping delay with William Lloyd Garrison, Charles Lenox Remond and Nathaniel Peabody Rogers to hear that the female delegates had been excluded from the main proceedings. Reputedly they had been voted from the floor by clergyman who were generally not from the Church of England. In protest the four men took up seats with the sidelined women delegates.[5] Adam said at the convention "If women had no right there, he had none, his credentials were from the same persons and the same society."[3]

He resigned his professorship at Harvard so he could stay in London for over a year whilst he edited the British Indian Advocate for the British India society[3] before he decided to join, and invest in, an experimental society named the Northampton Association of Education and Industry in Massachusetts.[1]

In 1843 he was reporting on the British Anti-Slavery movement to Americans according to William Lloyd Garrison as well as serving as the secretary of the British India Society.[6] He lost control of his investment in the Northampton Utopian Society and in the winter of 1844 he was teaching to Boston's women.[1]

Canada and America

Adam returned to his ministry where Samuel Joseph May and the American Unitarian Association's advice led to him being appointed the first Unitarian minister in Toronto in 1845. He had some brief success but by the following year he was a minister at the First Unitarian Church of Chicago. This did not turn out to be a long term appointment either and his next recorded Unitarian sermon was in Essex in 1855. He has been described as "first international Unitarian of modern times", even though that by 1861 he had renounced Unitarianism.[1]

England

Adam died in Beaconsfield in 1881 and at his own request he was buried in an unmarked grave. His wealth was left to create scholarships for the students at the local grammar school. These scholarships were to be awarded specifically without regard to any prejudice.[3]

References

- Hill, Andrew. "William Adam". Dictionary of Unitarian & Universalist Biography. Unitarian Universalist History and Heritage Society. Archived from the original on 23 September 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- https://archive.org/details/TheBeautifulTree-Dharampal/page/n9/mode/2up/search/william

- Hill, Andrew. "William Adam:A noble Specimen" (PDF). Canadian UU History Society. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- Major, Andrea (2012). Slavery, Abolitionism and Empire in India, 1772–1843 p.235. Liverpool University Press. p. 361.

- Annual Report of the Mass. Anti Slavery Society. Boston: Dow & Jackson. 1843.

- Garrison, William Lloyd (1974). The letters of William Lloyd Garrison: No union with slaveholders, 1841–1849 p. 192. Harvard University Press. p. 750.