Why–because analysis

Why–because analysis (WBA) is a method for accident analysis.[1] It is independent of application domain and has been used to analyse, among others, aviation-, railway-, marine-, and computer-related accidents and incidents. It is mainly used as an after the fact (or a posteriori) analysis method. WBA strives to ensure objectivity, falsifiability and reproducibility of results.

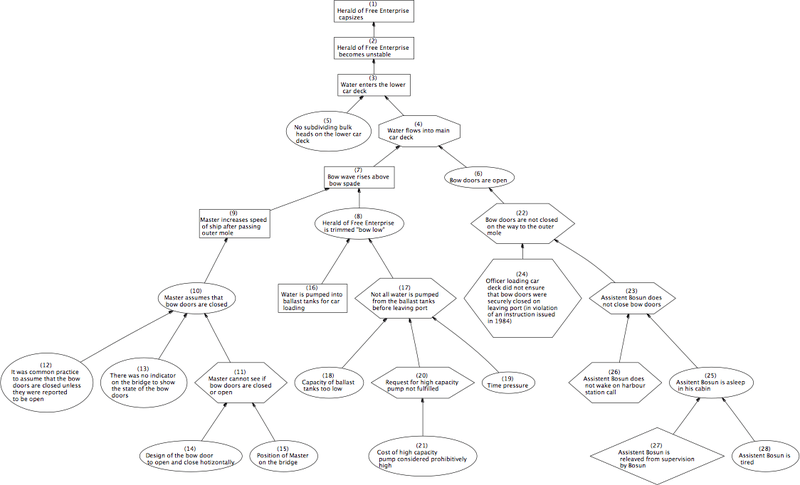

The result of a WBA is a why–because graph (WBG). The WBG depicts causal relations between factors of an accident. It is a directed acyclic graph where the nodes of the graph are factors. Directed edges denote cause–effect relations between the factors.

WBA in detail

WBA starts with the question "What is the accident or accidents in question?". In most cases this is easy to define. Next comes an iterative process to determine causes. When causes for the accident have been identified, formal tests are applied to all potential cause-effect relations. This process can be iterated for the newfound causes, and so on, until a satisfactory result has been achieved.

At each node (factor), each contributing cause (related factor) must have been necessary to cause the accident, and the totality of causes must have been sufficient to do so.

The formal tests

The counterfactual test (CT) – The CT leads back to David Lewis' formal notion of causality and counterfactuals. The CT asks the following question: "If the cause had not been, could the effect have happened?". The CT proves or disproves that a cause is a necessary causal factor for an effect. Only if it is necessary for the cause in question then it is clearly contributing to the effect.

The causal sufficiency test – The CST asks the question: "Will an effect always happen if all attributed causes happen?". The CST aims at deciding whether a set of causes are sufficient for an effect to happen. The missing of causes can thus be identified.

Only if for all causal relations the CT is positive and for all sets of causes to their effects the CST is positive the WBG is correct: each cause must be necessary (CT), and the totality of causes must be sufficient (CST): nothing is omitted (CST: the listed causes are sufficient), and nothing is superfluous (CT: each cause is necessary).

Example

See also

References

- Ladkin, Peter; Loer, Karsten (April 1998). Analysing Aviation Accidents Using WB-Analysis - an Application of Multimodal Reasoning (PDF). Spring Symposion. Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence.

External links

- Why-Because Analysis (WBA)