Whitefriars Theatre

The Whitefriars Theatre was a theatre in Jacobean London, in existence from 1608 to the 1620s — about which only limited and sometimes contradictory information survives.

Location

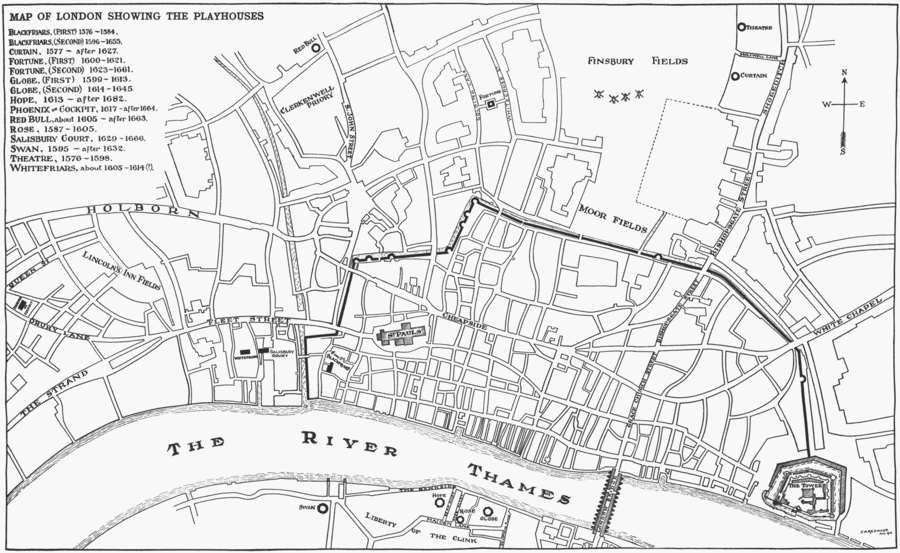

The Whitefriars district was outside the medieval city walls of London to the west; it took its name from the priory of Carmelite monks ("white friars" due to their characteristic robes) that had existed there before Henry VIII's Dissolution of the Monasteries. Until 1608 the Whitefriars district was a liberty of the City, beyond the direct control of the Lord Mayor and the aldermen; as such, it tended to attract the elements of society that had an interest in resisting authority. Like actors: there is a single reference to a theatre in Whitefriars that was suppressed sometime in the reign of Queen Elizabeth.

Theatre

In 1608, Michael Drayton and Thomas Woodford, nephew of the playwright, Thomas Lodge, leased the mansion house of the old priory from Lord Buckhurst, for a term of seven years. They constructed what was then called a "private" theatre (as opposed to the large open-air "public" theatres like the Globe) in the refectory or hall of the building. The new theatre was occupied at first by the King's Revels Children during that company's brief life. In 1609 their place was taken by the Children of the Queen's Revels; that company acted Nathan Field's play A Woman is a Weathercock there, as well as Ben Jonson's Epicene, George Chapman's The Revenge of Bussy D'Ambois, Beaumont and Fletcher's The Scornful Lady, John Marston's The Insatiate Countess, and Robert Daborne's A Christian Turn'd Turk.[1]

The Queen's Revels Children were joined in 1613 by the Lady Elizabeth's Men. The intention may have been for the combined company to use the Whitefriars as its winter playhouse and the Swan Theatre as a summer venue, as the King's Men did with the Blackfriars Theatre and the Globe.[2] But Philip Rosseter, the manager of the Queen's Revels company, lost his lease on the Whitefriars in 1614 and was unable to renew it. The combined company split again, and by October 1614 the Lady Elizabeth's Men were at the newly opened Hope Theatre south of the Thames.

In 1615 the Queen's Revels players moved to Rosseter's short-lived Porter's Hall Theatre and then passed out of existence. After that point, the story of the Whitefriars Theatre grows obscure; Prince Charles's Men may have used the theatre, though they were also acting at the Hope. A 1616 reference pictures the place as poorly furnished and suffering from rain damage. In 1621 the building's then-current landlord, Sir Anthony Ashley, "turned out the players."[3]

Replacement

In 1629 the Whitefriars was replaced by the Salisbury Court Theatre, which was located across Water Lane (now the southern end of Whitefriars St) from the Whitefriars, where the KPMG headquarters now stands. Salisbury Court was named after the medieval house and garden of the Bishops of Salisbury, which stood on the east side of Water Lane.[4] To add an element of posthumous confusion, the Salisbury Court Theatre was sometimes referred to as the Whitefriars in later years, as in the 1660s diary of Samuel Pepys.

The site of the Whitefriars priory is now occupied by the offices of Freshfields; a fragment of the priory cellars has been excavated and moved to a basement that can be viewed from Magpie Alley.

Notes

- Munro, p. 25.

- R. A. Foakes, "Playhouses and players," in Braunmuller and Hattaway, p. 30.

- Chambers, Vol. 2, pp. 515-17.

- Clapham, p. 17 and fig. facing.

References

- Braunmuller, A. R., and Michael Hattaway, eds. The Cambridge Companion the English Renaissance Drama. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Clapham, A. W., "The topography of the Carmelite Priory of London," Journal of the British Archaeological Association New Series 16 part 1 (March 1910), pp. 15–32.

- Chambers, E. K. The Elizabethan Stage. 4 Volumes, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1923.

- Halliday, F. E. A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964. Baltimore, Penguin, 1964.

- Munro, Lucy. The Children of the Queen's Revels: A Jacobean Theatre Repertory. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2005.

External links

- Shakespearean Playhouses, by Joseph Quincy Adams, Jr. from Project Gutenberg