White-necked thrush

The white-necked thrush (Turdus albicollis) is a songbird found in forest and woodland in South America. The taxonomy is potentially confusing, and it sometimes includes the members of the T. assimilis group as subspecies, in which case the "combined species" is referred to as the white-throated thrush (a name limited to T. assimilis when the two are split). On the contrary, it may be split into two species, the rufous-flanked thrush (T. albicollis) and the grey-flanked thrush (T. phaeopygos).

| White-necked thrush | |

|---|---|

| |

| Turdus a. albicollis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Turdidae |

| Genus: | Turdus |

| Species: | T. albicollis |

| Binomial name | |

| Turdus albicollis Vieillot, 1816 | |

| |

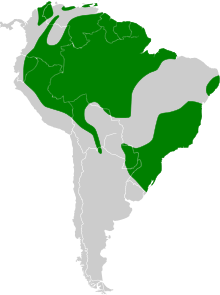

| Range of white-necked thrush (green) in South America | |

Description

_(4089539829).jpg)

This thrush is 20 1⁄2–26 cm (8.1–10.2 in) long and weighs 40–77 g (1.4–2.7 oz).[2] The upperparts are dark brown, turning duskier or greyer towards the ocular region. The throat is white with dense dark streaks, except on the lowermost part, resulting in the appearance of a white crescent below the dark-streaked white throat. This has given rise to both its English and scientific name. The crissum (the undertail coverts surrounding the cloaca) and central belly are whitish, and the chest is grey often tinged brown. The members of the nominate group have conspicuous rufous flanks, and the bill is yellow with a dusky culmen. The flanks are paler and more tawny in the subspecies crotopezus, which also has the entire upper mandible dusky. The members of the phaeopygos group lack contrasting rufous or tawny flanks, and have bills that are almost entirely dusky. All subspecies have pinkish-brown legs and a reddish or yellow eye-ring.[2] Sexes are similar, but juveniles are duller, with dull orange spotting above, and brownish spotting below.[3]

The song is a relatively musical, often rather monotonous[4] two-e-o, two-e. The calls is a distinctive wuk, while the alarm is a rough jjig-wig-wig.[2]

Distribution and habitat

The nominate group (including subspecies paraguayensis and crotopezus) occurs in eastern Brazil, far northern Uruguay, eastern Paraguay and far north-eastern Argentina. The phaeopygos group (including subspecies phaopygoides, spodiolaemus and contemptus) is mainly found in the Amazon Basin, but with populations extending along the eastern slope of the Andes as far south as north-eastern Argentina, and as far north as western Venezuela, with extensions along the Coastal Range, the region centered around Serranía del Perijá and Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, and the islands of Trinidad and Tobago.[2][4]

Both groups are mainly associated with humid forest and woodland. In the case of the nominate group, mainly the Atlantic Forest, and in the case of the phaeopygos group, mainly the Amazon Rainforest or humid forests and woodlands near mountains. It rarely ventures far from cover.[2]

Behavior

The white-necked thrush mainly feeds on or near the ground on invertebrates. It also takes some fruit and berries.[2] It regularly follows army ant swarms, but does not attend mixed species flocks.[4] Throughout most of its range, especially in the Amazon, it is a shy species, heard far more than seen, but in Trinidad and parts of south-eastern Brazil it may be less retiring.

The nest is a lined cup of twigs placed low (at a height of 1–9 m [3.3–29.5 ft][2]) in a tree or bush. Two to three reddish-blotched green-blue eggs are laid and incubated by the female alone for 12–13 days. Social mongamous, but extra-pair mate are common.[5]

Taxonomy

T. albicollis sometimes includes the members of the T. assimilis group as subspecies, in which case the "combined species" is referred to as the white-throated thrush (a name limited to T. assimilis when the two are split). Published evidence supporting either treatment is weak, but most recent authorities have followed the split.[6]

On the contrary, it has been suggested that the nominate group and the phaeopygos group of T. albicollis should be considered separate species, but the voices of the two are similar, and the subspecies crotopezus from the nominate group approach members of the phaeopygos group in both plumage and colour of bill.[7] If the two groups are split, the common name rufous-flanked thrush has been suggested for T. albicollis, with T. phaeopygos retaining the common name white-necked thrush or being renamed grey-flanked thrush.[2][7]

Footnotes

- BirdLife International (2012). "Turdus albicollis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collar (2005)

- Restall et al. (2006)

- Hilty (2003)

- Biagolini-Jr, Carlos; Costa, Mariellen C.; Perrella, Daniel F.; Zima, Paulo V. Q.; Ribeiro-Silva, Lais; Francisco, Mercival R.; Biagolini-Jr, Carlos; Costa, Mariellen C.; Perrella, Daniel F. (2016). "Extra-pair paternity in a Neotropical rainforest songbird, the White-necked Thrush Turdus albicollis (Aves: Turdidae)". Zoologia (Curitiba). 33 (4). doi:10.1590/S1984-4689zool-20160068. ISSN 1984-4670.

- Remsen et al. (2008)

- Ridgely & Greenfield (1989)

References

- Clement, Peter & Hathaway, Ren (2000): Thrushes. Christopher Helm, London. ISBN 0-7136-3940-7

- Collar, N. J. (2005). White-throated Thrush (Turdus albicollis). Pp. 663 in: del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; & Christie, D. A. eds. (2005). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 10. Cuckoo-shrikes to Thrushes. Lynx Edicion, Barcelona. ISBN 84-87334-72-5

- ffrench, Richard; O'Neill, John Patton & Eckelberry, Don R. (1991): A guide to the birds of Trinidad and Tobago (2nd edition). Comstock Publishing, Ithaca, N.Y. ISBN 0-8014-9792-2

- Greeney, Harold F.; Gelis, Rudolphe A. & White, Richard (2004): Notes on breeding birds from an Ecuadorian lowland forest. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club 124 (1): 28–37. PDF fulltext

- Hilty, Steven L. (2003): Birds of Venezuela. Christopher Helm, London. ISBN 0-7136-6418-5

- Remsen, J. V., Jr.; Cadena, C. D.; Jaramillo, A.; Nores, M.; Pacheco, J. F.; Robbins, M. B.; Schulenberg, T. S.; Stiles, F. G.; Stotz, D. F.; & Zimmer, K. J. (2008). A classification of the bird species of South America. American Ornithologists' Union. Accessed 2008-08-07

- Restall, Robin L.; Rodner, C. & Lentino, M. (2006): Birds of Northern South America. Christopher Helm, London. ISBN 0-7136-7243-9 (vol. 1). ISBN 0-7136-7242-0 (vol. 2).

- Ridgely, R. S.; & Tudor, G. (1989): The Birds of South America - The Oscine Passerines (vol. 1). Oxford University Press, Oxford. ISBN 0-19-857217-4

External links

- Turdus albicollis, "White-necked Robin" videos on the Internet Bird Collection

- White-necked Thrush photo gallery VIREO Photo-High Res

- Photo-High Res; Article oiseaux