Wells Gray Park Cave discovery

The Wells Gray Park Cave discovery of 2018 was of a karst cave in Wells Gray Provincial Park, in the Cariboo Mountains in British Columbia, Canada. The cave has informally been named Sarlacc's Pit pending an official name.[1]

| Cave in Wells Gray Provincial Park | |

|---|---|

An aerial view of the cave entrance. | |

| Location | Wells Gray Provincial Park |

| Coordinates | 52°31′00″N 120°02′35″W |

| Depth | 500 m (1,600 ft) (est.) |

| Length | 2,100 m (6,900 ft) (est.) |

| Discovery | April 2018 |

| Geology | stripe karst |

| Entrances | 1 |

| Hazards | meltwater flow |

Discovery and exploration

In the spring of 2018, a Canadian government team was surveying caribou populations by helicopter when the pilot, Ken Lancour, spotted a deep, snow-filled depression at the cave entrance.[2][3] The team named the cave Sarlacc's Pit, in reference to the iconic Sarlacc creature from the film Return of the Jedi.[2][3] The name, however, remains unofficial until a naming consultation can be held with First Nations in the area.[1][3][4]

In September 2018, a team led by geologist Catherine Hickson and archaeological surveyor John Pollack returned to the site and made a partial descent into the cave once it was snow-free, estimating it to be at least two kilometres (1.2 mi) long.[1][2][3][4] The ground reconnaissance expedition estimated the physical dimensions of the cave. The team plans to return for more extensive explorations in 2020.[1][3][4]

The discoverers wished to keep the location secret to prevent environmental damage to the cave from visitors.[1][4] In addition, the Government of British Columbia closed the area around the cave in the interests of preservation and public safety.[5][6]

Geography and geology

Media reports have claimed that Sarlacc's Pit is the largest known stripe karst cave.[1][2] A potentially deeper stripe karst cave is the Cascade Tupper System at 483 m, and a potentially longer one is the White Rabbit at 1 km.[7][8] Preliminary estimates suggest that Sarlacc's Pit may also have the largest cave entrance in Canada.[1] Its entrance is 100 metres (330 ft) long by 60 metres (200 ft) wide[1][2][3][4] and is at least 135 metres (443 ft) deep.[1] A river flows into the entrance, becoming a waterfall and sending up mist that has prevented measuring the exact depth of the cave.[1][2]

The cave is normally snow-covered for much of the year and sits at the bottom of a massive avalanche slope.[3][4] Early fall may be the only practical season to explore the cave because this is when the waterfall that fills the entrance experiences its lowest flow; in spring, meltwater flow of between 5 to 15 cubic metres per second (177 to 530 cu ft/s) prevents entrance.[3] The cave may have been snow-covered year-round until the 20th century. This would suggest that it has not been explored by First Nations people, and the technical gear required, combined with the depth of the entrance shaft, means passing mountaineers in the last few decades are also unlikely to have explored it.[3][4]

See also

- List of caves in Canada

- List of deepest caves

- Karst cave

Gallery

Descent of 90 m into cave

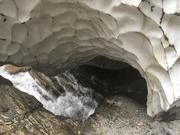

Descent of 90 m into cave Cave entrance in winter

Cave entrance in winter

References

- The Canadian Press (3 December 2018). "Newly discovered cave in B.C. might be largest ever found in Canada". CBC News. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- "'Awe-inspiring' cave discovered in Canada's wilderness". BBC News. 3 December 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- Wilson, Harry (30 November 2018). "Canadian team confirms presence of huge unexplored cave in British Columbia". Canadian Geographic. Canadian Geographic Enterprises. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- Little, Simon (2 December 2018). "Massive, unexplored 'cave of national significance' discovered in B.C. park". Global News. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- Schmunk, Rhianna (Dec 19, 2018). "Visiting B.C.'s huge, newly discovered cave could land you a $1M fine". CBC News. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- "Wells Gray Park Closure Notice December 17, 2018". Wells Gray Park. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- Yonge, C.J., Viera, N. and Walker, N. (2013). "The Tupper – Raspberry Rising Cave System: A Remarkable Example in Stripe Karst" (PDF). 16th International Congress of Speleology. ICS Proceedings, BRNO Czech Republic: 158–163.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Yonge, C.J. (2018). "White Rabbit, Monashee - Geology, Speleogenesis and Cave Depth Potential". Canadian Caver. 84: 5–9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wells Gray Park Cave discovery. |