Weisskunig

Der Weisskunig or The White King is a chivalric novel[1] and thinly disguised biography of the Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian I, (1486–1519) written in German by Maximilian and his secretary between 1505 and 1516. Although not explicitly identified as such in the book, Maximilian appears as the "young" White King, with his father Frederick III represented as the "old" White King.

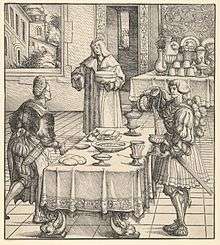

The book is now mainly remembered for the 251 woodcut illustrations, made in Augsburg between 1514 and 1516, the principal artists for which were Hans Burgkmair and Leonhard Beck.[2] The work was never completed, and the full published edition did not appear until 1775.

Background

Maximilian I, and his father Frederick III, were part of what was to become a long line of Holy Roman Emperors from the House of Habsburg. Maximilian was elected King of the Romans in 1486 and succeeded his father on his death in 1493.

During his reign Maximilian commissioned a number of humanist scholars and artists to assist him complete a series of projects, in different art forms, intended to glorify for posterity his life and deeds and those of his Habsburg ancestors.[3][4] He referred to these projects as Gedechtnus ("memorial"),[4][5] and included a series of stylised autobiographical works, of which Der Weisskunig was one, the others being the poems Freydal and Theuerdank.[3]

Composition and publication

Der Weisskunig, which was never completed, is a prose work written in German[3] by Maximilian’s secretary, Marx Treitzsauerwein, although sections were dictated to him by Maximilian himself.[2] Treitzsauerwein has been described as Maximilian's "ghostwriter".[1] It was composed between 1505 and 1516.[6] After Maximilian’s death in 1519, his grandson, Ferdinand, commissioned Treitzsauerwein to complete the book, but it remained unfinished because of Treitzsauerwein’s death in 1527.[2]

Maximilian did not intend the work to be published commercially; copies were presented to specially selected recipients.[3] Although a print was made in 1526,[3] the full work was not published until 1775.[7]

Content

According to H.G. Koenigsberger, the book combines “the style and manner of Arthurian legend with romanticised autobiography”.[1] The story is based on the lives of Maximilian, fictionalised as the “young” White King, and his father, the “old” White King, Frederick III, and recounts their dealings with contemporary characters whose identities are disguised but easily decipherable.[8][9] These include the Blue King (the King of France), the Green King (the King of Hungary) and the King of Fish (representing Venice).[9] Maximilian is depicted as a virtuous ruler favoured by God.[10]

The book is divided into three parts: the first covers the life of Maximilian’s father; the second part begins with Maximilian’s birth in 1459 and ends with his marriage to Mary of Burgundy in 1477; and the third part is an account of Maximilian’s life to 1513.[2]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Weißkunig. |

- Koenigsberger, H. G. (22 November 2001). Monarchies, States Generals and Parliaments: The Netherlands in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. Cambridge University Press. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-0-521-80330-4.

- Smith, Jeffrey Chipps (15 December 2014). Nuremberg, a Renaissance City, 1500–1618. University of Texas Press. p. 419. ISBN 978-1-4773-0638-3.

- Watanabe-O'Kelly, Helen (12 June 2000). The Cambridge History of German Literature. Cambridge University Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-521-78573-0.

- Westphal, Sarah (20 July 2012). "Kunigunde of Bavaria and the 'Conquest of Regensburg': Politics, Gender and the Public Sphere in 1485". In Emden, Christian J.; Midgley, David (eds.). Changing Perceptions of the Public Sphere. Berghahn Books. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-85745-500-0.

- Kleinschmidt, Harald (January 2008). Ruling the Waves: Emperor Maximilian I, the Search for Islands and the Transformation of the European World Picture C. 1500. Antiquariaat Forum. p. 162. ISBN 978-90-6194-020-3.

- Heer, Friedrich (1995). The Holy Roman Empire. Phoenix Giant. p. 144. ISBN 1-85799-367-5.

- Sutter Fichtner, Paula (15 May 2014). The Habsburgs: Dynasty, Culture and Politics. Reaktion Books. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-78023-314-7.

- Biddle, Martin; Badham, Sally (2000). King Arthur's Round Table: An Archaeological Investigation. Boydell & Brewer. p. 470. ISBN 978-0-85115-626-2.

- Silver, Larry (2000). "Caesar Ludens: Emperor Maximilian I and the waning of the middle ages". In Schine Gold, Penny; Sax, Benjamin C. (eds.). Cultural Visions: Essays in the History of Culture. Rodopi. pp. 192–193. ISBN 90-420-0490-8.

- Frieder, Braden K. (1 January 2008). Chivalry & the Perfect Prince: Tournaments, Art, and Armor at the Spanish Habsburg Court. Truman State Univ Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-935503-32-3.