Wedge-tailed sabrewing

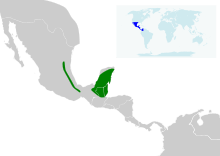

The wedge-tailed sabrewing (Pampa pampa) is a species of hummingbird in the family Trochilidae. It is found in Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico. Its natural habitats are subtropical or tropical moist lowland forest and heavily degraded former forest.

| Wedge-tailed sabrewing | |

|---|---|

| |

| In Belize | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Apodiformes |

| Family: | Trochilidae |

| Genus: | Pampa |

| Species: | P. pampa |

| Binomial name | |

| Pampa pampa Lesson, 1832 | |

| |

Taxonomy

There were once three recognized subspecies of wedge-tailed sabrewing (under the scientific name P. curvipennis), but all are now considered separate species, which have completely separate ranges.[1][2] Curve-winged sabrewing (P. curvipennis) occurs closest to the U.S. border and has a slightly longer bill than P. pampa, which occurs from Honduras[3] to the Yucatán Peninsula. Long-tailed sabrewing (P. excellens) is the other taxon.[4]

Other authors suggest P. curvipennis is a species complex composed of three allopatrically distributed lineages corresponding to the previous named groups. Also they are all divergent in morphology and acoustics.

Description

The wedge-tailed sabrewing is a large hummingbird with a long wedge-shaped tail. Upperparts are green with blue to violet-blue crown that blends into the green nape. It has a white spot behind its eyes and a dark gray cheek. Underparts are pale gray to whitish, often slightly darker laterally. The bill is long and ranges from straight to slightly decurved, and the lower mandible is pinkish at base.[1] The adult male is slightly larger than the female, but other than that sexes are similar, is a sexually monochromatic, size dimorphic hummingbird.[1][5] Juveniles are similar to adults but duller in coloring.[1]

P.c. pampa are 5½ inches long.[3] Males weigh 6½ grams and females weigh 5 grams.[3] Its eyes are very dark brown, appearing black, and legs are dark brown.[3]

Distribution and habitat

The wedge-tailed sabrewing resides in humid tropical forests, woodlands, and dense second growth, ranging from near sea level to 4500 feet above sea level.[1] It is not known to migrate.[1]

Behavior

The wedge-tailed sabrewing often forages along walls of vegetation at forest edges and on steep slopes.[1] Its flight style varies from the rapid wingbeats of typical hummingbirds to slower wingbeats like those of swifts. It is bold and curious, and often approaches humans.[1] It breeds from March to July, and its nest is a well-camouflaged cup attached to a horizontal branch.[1] Males are polygynous and during the breeding season they congregate in leks, broadcasting elaborate vocalizations into the environment.[5]

Vocalization

Calls include steady, persistent chipping and a shrill, nasal peek. The wedge-tailed sabrewing usually sings from dense vegetation, and its songs are complex and variable, usually including insect-like chips, squeaks, and squeals, followed by a series of excited warbled or gurgling notes.[1] Males sing year-round, sometimes in small groups. Some tail or wing movements are associated with perched singing displays.[1] The wedge.tailed sabrewings display songs with many levels of geographic variation, mos notably the introductory syllable and the repertoire syllabels.

Song Evolution

There is independence between acoustic and neutral genetic divergence in this hummingbirds species. Along the continous distribution of this species theres no genetic divergence suggesting the homogenizing force of gene flow. [5] Geographical structure of vocal variation corresponds with the restricted south to north gene flow between geographic areas of the Sierra Madre Oriental. Evolution of song elaboration in wedge-tailed sabrewing resulted from a combination of processes probably linked to postdispersal learning, isolation by distance, and social factors associated with male-male interactions.[5] With negligible geographic barriers and no behavioral checks on dispersal, little genetic differentiation has developed in wedge-tailed sabrewings along the Sierra Madre Oriental despite the apparent intense social (and sexual) selection acting on the elaborate acoustic traits. Although learning and cultural drift are real possibilities, there may be cultural selection reinforced by selection for imitation driving which songs can be learned, and coupled patterns of genetic and acoustic divergence could emerge when barriers become strong enough to gene flow.[5]

References

- Williamson, Sheri L. (2001). Hummingbird of North America. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-618-02496-4.

- "Campylopterus curvipennis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- Smithe, Frank B. (1966), The Birds of Tikal, Illustrated by H. Wayne Trimm (1st ed.), Garden City, NY: Published for the American Museum of Natural History [by] the Natural History Press, OCLC 555759

- IUCN. "Campylopterus excellens". Retrieved 5 January 2007.

- González, Clementina; Ornelas, Juan Francisco (1 October 2014). Bolhuis, Johan J. (ed.). "Acoustic Divergence with Gene Flow in a Lekking Hummingbird with Complex Songs". PLOS ONE. 9 (10): e109241. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j9241G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0109241. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4182805. PMID 25271429.