Anax

Anax (Greek: Ἄναξ; from earlier ϝάναξ, wánax) is an ancient Greek word for "tribal chief, lord, (military) leader".[1] It is one of the two Greek titles traditionally translated as "king", the other being basileus, and is inherited from Mycenaean Greece, and is notably used in Homeric Greek, e.g. for Agamemnon. The feminine form is anassa, "queen" (ἄνασσα, from wánassa, itself from *wánakt-ja).[2]

Etymology

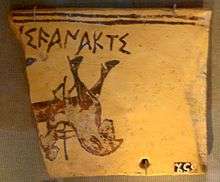

The word anax derives from the stem wanakt- (nominative *ϝάνακτς, genitive ϝάνακτος), and appears in Mycenaean Greek written in Linear B script as 𐀷𐀙𐀏, wa-na-ka,[3] and in the feminine form as 𐀷𐀙𐀭, wa-na-sa[4] (later ἄνασσα, ánassa). The digamma ϝ was pronounced /w/ and was dropped very early on, even before the adoption of the Phoenician alphabet, by eastern Greek dialects (e.g. Ionic Greek); other dialects retained the digamma until well after the classical era.

The word Anax in the Iliad refers to Agamemnon (ἄναξ ἀνδρῶν, i.e. "leader of men") and to Priam, high kings who exercise overlordship over other, presumably lesser, kings. This possible hierarchy of one "anax" exercising power over several local "basileis" probably hints to a proto-feudal political organization of Aegean civilizations. The Linear B adjective 𐀷𐀙𐀏𐀳𐀫, wa-na-ka-te-ro (wanákteros), "of the [household of] the king, royal",[5] and the Greek word ἀνάκτορον, anáktoron, "royal [dwelling], palace"[6] are derived from anax. Anax is also a ceremonial epithet of the god Zeus ("Zeus Anax") in his capacity as overlord of the Universe, including the rest of the gods. The meaning of basileus as "king" in Classical Greece is due to a shift in terminology during the Greek Dark Ages. In Mycenaean times, a *gʷasileus appears to be a lower-ranking official (in one instance a chief of a professional guild), while in Homer, Anax is already an archaic title, most suited to legendary heroes and gods rather than for contemporary kings.

The Greek title has been compared to Sanskrit vanij, a word for "merchant", but in the Rigveda once used as a title of Indra. The word could then be from Proto-Indo-European *wen-aǵ-, roughly "bringer of spoils" (compare the etymology of lord, "giver of bread"). However, Robert Beekes argues there is no convincing IE etymology and the term is probably from the pre-Greek substrate.

The word is found as an element in such names as Hipponax ("king of horses"), Anaxagoras ("king of the agora"), Pleistoanax ("king of the multitude"), Anaximander ("king of the estate"), Anaximenes ("enduring king"), Astyanax ("high king", "overlord of the city") Anaktoria ("royal [woman]"), Iphiánassa ("mighty queen"), and many others. The archaic plural Ánakes (Ἄνακες, "Kings") was a common reference to the Dioskouroi, whose temple was usually called the Anakeion (Ἀνάκειον) and their yearly religious festival the Anákeia (Ἀνάκεια).

The words ánax and ánassa are occasionally used in Modern Greek as a deferential to royalty, whereas the word anáktoro[n] and its derivatives are commonly used with regard to palaces.

See also

References

- ἄναξ. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- Beekes, Robert (2010) [2009]. "S.v. ἄναξ". Etymological Dictionary of Greek. 1. With the assistance of Lucien van Beek. Leiden, Boston: Brill. pp. 98–99. ISBN 9789004174184.

- "The Linear B word wa-na-ka". Palaeolexicon. Word study tool of ancient languages.

- "The Linear B word wa-na-sa". Palaeolexicon. Word study tool of ancient languages.

- "The Linear B word wa-na-ka-te-ro". Palaeolexicon. Word study tool of ancient languages.

- ἀνάκτορον in Liddell and Scott.

Further reading

- Haskell, Halford W. "Wanax to Wanax: Regional Trade Patterns in Mycenaean Crete." Hesperia Supplements 33 (2004): 151-60. www.jstor.org/stable/1354067.

- Hooker, James T. (1979). "The Wanax in Linear B Texts". Kadmos. 18 (2): 100–111. doi:10.1515/kadm.1979.18.2.100. ISSN 0022-7498.

- Kilian, Klaus (1988). "The Emergence of Wanax Ideology in the Mycenaean Palaces". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 7 (3): 291–302. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0092.1988.tb00182.x.

- Ndoye, Malick. Grandeur et décadence des anaktes dans les poèmes homériques. In: Troïka. Parcours antiques. Mélanges offerts à Michel Woronoff, volume 1. Besançon : Institut des Sciences et Techniques de l'Antiquité, 2007. pp. 73-84. (Collection « ISTA », 1079) [www.persee.fr/doc/ista_0000-0000_2007_ant_1079_1_2657]

- Poldrugo, Floriana. "LA PERSISTENZA DELLA FIGURA DEL "WANAX" MICENEO A CIPRO IN ETÀ STORICA." Studi Classici E Orientali 47, no. 1 (2001): pp. 21-51. www.jstor.org/stable/24186872.

- Perpillou, Jean-Louis. Le wanax entre actif et moyen. In: Autour de Michel Lejeune. Actes des journées d'études organisées à l'Université Lumière Lyon 2 – Maison de l'Orient et de la Méditerranée, 2-3 février 2006. Lyon : Maison de l'Orient et de la Méditerranée Jean Pouilloux, 2009. pp. 153-167. (Collection de la Maison de l'Orient méditerranéen ancien. Série philologique, 43) [www.persee.fr/doc/mom_0184-1785_2009_act_43_1_2658]

- Palaima, Thomas G. (1995). "The Nature of the Mycenaean Wanax: Non-Indo-European Origins and Priestly Functions". In Rehak, Paul (ed.). The Role of the Ruler in the Prehistoric Aegean. Aegaeum. 11. Liège: Univ., Histoire de l'Art et Archéologie de la Grèce Antique. pp. 119–139. ISBN 90-429-2411-X.

- Schon, Robert. "Redistribution in Aegean Palatial Societies. By Appointment to His Majesty the Wanax: Value-Added Goods and Redistribution in Mycenaean Palatial Economies." American Journal of Archaeology 115, no. 2 (2011): 219-27. Accessed May 11, 2020. doi:10.3764/aja.115.2.0219.

- Willms, Lothar (2010). "On the IE Etymology of Greek (w)anax". Glotta. 86: 232–271. JSTOR 41219890.

- Yamagata, Naoko (1997). "ἄναξ and βασιλεύς in Homer". Classical Quarterly. 47 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1093/cq/47.1.1. ISSN 0009-8388.