Walhonding Canal

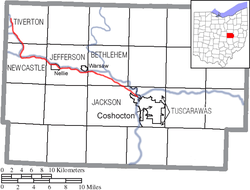

The Walhonding Canal was a canal in Coshocton County, Ohio that was used as a feeder canal for the Ohio and Erie Canal. A small canal, at only 25 miles (40.2 km) long, it was wholly contained within Coshocton County, following the Mohican River from Cavallo south to the confluence with the Kokosing River, which together with the Mohican forms the Walhonding River. The canal followed the Walhonding River southeast toward Coshocton where it met the Ohio and Erie Canal in Roscoe Village.

| Walhonding Canal | |

|---|---|

View of the bottom of the "Triple Locks", a series of three locks where the Walhonding Canal emptied into Roscoe Basin and met the Ohio and Erie Canal in Roscoe Village, Ohio. | |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 25 km (16 miles) |

| Minimum boat draft | 4 ft (1.2 m) |

| Locks | 13 |

| History | |

| Date of act | 1836 |

| Date closed | 1896 (abandoned) |

Establishment and construction

Building of the Walhonding Canal commenced in 1836 and finished in 1842. William H. Price, Charles J. Ward, John Waddle, Jacob Blickensderfer, Henry Fields and Sylvester Medbery were among the members of the engineering corps responsible for the Walhonding Canal. Several of these men also served as contractors on the Ohio and Erie Canal. In addition to these were John Frew, S. Moffit, Isaac Means, John Crowley, W. K. Johnson and others. It cost $607,268.99, or an average of $24,290.76 per mile.[1]

The Superintendents of the Walhonding canal were Langdon Hogle, John Perry, William E. Mead and Charles H. Johnson. The first canal boat launched in the county was called the "Renfrew" in honor of James Renfrew, a merchant of Coshocton. It was built by Thomas Butler Lewis, an old Ohio keel-boatman.[1]

Extensions

It was intended to have the Walhonding canal extended to the northwestern part of Ohio, but there was already much talk of speedier mode of conveyance in 1842. The work being very expensive, and the members of the legislature from districts where canals were no longer regarded as practicable were unwilling to support the necessary appropriations. Two years after initial approval of the canal, the Board of Public Works lobbied for authorization of extensions for the canal. One proposal was a 23 miles (37.0 km) extension north along the Mohican River and the other proposal was a 21 miles (33.8 km) extension west along the Kokosing River toward Mount Vernon in Knox County. By 1844 the lobbyists for extensions realized neither would gain approval and they soon stopped requesting appropriations.[1]

The extensions up the Kokosing River to Mount Vernon and north along the Mohican River to Loudonville was first authorized by the Ohio General Assembly on March 10, 1838. The extension to Mount Vernon was contingent on the Mount Vernon Lateral Canal Company surrendering to the state their charter, rights, and privileges that would have interfered with the state of Ohio's interest in construction of the canal. The extensions would have to be surveyed and approved by the Ohio Board of Public Works before construction could begin and they would have to operate at cost seven years after completion.[2]

Railroad controversy

Traffic began to slow as other modes of transportation began to improve and need for the canal dwindled. In 1889, the Pennsylvania Company organized the Walhonding Valley Railroad that would follow the route of the canal from Coshocton to Loudonville. The Walhonding Valley Railroad was soon consolidated with the Northwestern Ohio Railroad, which formed the Toledo, Walhonding Valley and Ohio Railroad. The railroad was completed four years after the organization of the Walhonding Valley Railroad and it used some canal property on its right-of-way as it built the railroad, an action which led to a legal dispute.

Allegedly, the Pennsylvania Company had not obtained a warrant from the state in the early 1890s to use the abandoned canal property, though the railroad's attorneys stated that the Ohio Board of Public Works had given them a permit. No record of such a permit existed in the board's transactions, however. The Ohio Canal Commission and a legislative committee both investigated the proceedings in late 1892 and early 1893 and concluded that the railroad was occupying the state's canal property without permission. In the spring of 1893, the Ohio Legislature finally passed a resolution that directed the Ohio Attorney General, Republican John K. Richards, to bring proceedings in ouster against the Walhonding Railroad Company. The state's Canal Commission adopted a similar resolution in March 1893, asking Richards to bring suit in this case. An article in The New York Times reported that as of September 3, 1893, the railroad had been occupying the state's canal property for more than a year and it had been six months without an action on the part of Attorney General Richards or the Republican-controlled Board of Public Works. The New York Times article used this example as a means to illustrate how the author believed Republican control of the state government of Ohio was leading to corruption and destruction of public works.[3]

A suit was finally brought against the railroad company (by now the Toledo, Walhonding Valley and Ohio Railroad) by Attorney General Richards and was taken to the Supreme Court of Ohio. In order to settle the dispute, the legislature stepped in and passed an act (House Bill number 560) on May 14, 1894 that affirmed an agreement between the railroad and the canal commission. In the agreement, the railroad received the perpetual right to maintain its existing right-of-way on the berme bank of the canal and existing bridges over the canal for the sum of $5,000 in rents and tolls to the state. In return for this agreement, the state was allowed to at any time request the railroad move its right-of-way or raise the height of its bridges over the canals to the standard height of 10 feet (3.0 m) to allow for proper canal traffic.[4]

Abandonment

The state officially abandoned the Walhonding Canal in 1896 and the railroad that took its place continued to operate until 1936 when the Mohawk Dam was built for flood control, effectively cutting off the right-of-way.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Walhonding Canal. |

- Hill Jr., N.N. (1881). History of Coshocton County, Ohio: Its past and present, 1740-1881. Newark, Ohio: A. A. Graham & Co., Publishers. pp. 286-287.

- Ohio General Assembly. (1838). Acts of a local nature, passed at the first session of the Thirty-Sixth General Assembly of the State of Ohio, begun and held in the City of Columbus, December 4, 1837. Volume XXXVI. Columbus: Samuel Medary, Printer to the State. pp. 221-222.

- The New York Times. September 3, 1893. Only the public suffers: Illustrations of Republican misrule in the State of Ohio. Accessed online: 31 December 2007.

- Ohio General Assembly. (1894). General and... local acts passed and joint resolutions adopted by the Seventy-First General Assembly, at its regular session, begun and held in the City of Columbus, January 1st, 1894. Volume XCI. Norwalk, Ohio: Published by State Authority. The Laning PTG. Co., State Printers. pp. 232-234.

External links

- Ohio General Assembly. (1842). Documents, including messages and other communications made to the Fortieth General Assembly of the State of Ohio. Part I.-Vol. VI. Columbus: Samuel Medary, State Printer. pp. 6-8.