Walaric

Saint Walaric,[lower-alpha 1] modern French Valery (died 620), was a Frankish monk turned hermit who founded the abbey of Saint-Valery-sur-Somme. His cult was recognized in Normandy and England.

Life

Walaric was born in the Auvergne to a peasant family. Taught to read at a young age, he abandoned the occupation of tending sheep to join the abbey of Autumo. He later moved on to the abbey of Saint-Germain d'Auxerre and finally the abbey of Luxeuil under the famous abbot Columbanus. At Luxeuil he was renowned for his horticultural skills. His ability to protect his vegetables from insects was regarded as miraculous.[1]

When Theuderic II, king of Burgundy (r. 595–613), expelled Columbanus from his domains, Walaric and a fellow monk named Waldolanus left the kingdom to preach the gospel in Neustria and, according to tradition, the Pas-de-Calais. He eventually settled down as a hermit at a place called Leuconay near the mouth of the Somme River. A community of disciples grew up around him. After his death, his successor Blitmund (Blimont) built a monastery for the community, which came to bear Walaric's name. The village that developed around the monastery still does: Saint-Valery-sur-Somme.[1]

Memory

A biography (saint's life) of Walaric was composed in the 11th century. It was wrongly attributed to a certain Raginbertus.[1]

The so-called "Valerian prophecy" was a legend originating in Walaric's abbey and the abbey of Saint-Riquier intended to refute the claims of the early 11th-century Historia Francorum Senonensis that the Capetian dynasty were illegitimate usurpers. According to the legend, Walaric appeared in a vision to Hugh Capet (r. 987–996), the first Capetian, and thanked him for rescuing his body from the Carolingians. He prophesied that the kingdom of France would belong to Hugh's heirs "until the seventh generation". Interpreted figuratively, the number seven signified perfection and thus eternity; interpreted literally, it meant that the Philip Augustus (r. 1180–1223) would be the last Capetian.[2]

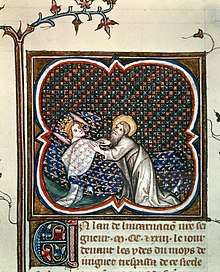

Cures were claimed from an early date at Walaric's tomb. Duke William II of Normandy had Walaric's relics put on public display and invoked his name in a prayer for a favourable wind for his invasion of England. The invasion fleet sailed from Saint-Valery-sur-Somme in 1066.[1]

Walaric's cult thus spread to England, where a chapel in Alnmouth was dedicated to him in the 12th century. His feast day was celebrated on 1 April in Chester Abbey and Croyland Abbey. King Richard I of England (r. 1189–1199) transferred his relics from Saint-Valery-sur-Somme to Saint-Valery-en-Caux. His translation (transfer of relics) was celebrated in Chester and Croyland on 12 December. His abbey in Saint-Valery-sur-Somme, however, later recovered his relics.[1]

The English village of Hinton Waldrist is named after its 12th-century lord, Thomas de Saint-Valery.[1]

Notes

- Also spelled Walric, Waleric, Walericus, Walarich, Gualaric, etc.

References

- David Hugh Farmer, "Walaric (Waleric, Valery) (d. 620)", The Oxford Dictionary of Saints, 5th rev. ed. (Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 441.

- John W. Baldwin, The Government of Philip Augustus: Foundations of French Royal Power in the Middle Ages (University of California Press, 1986), p. 370.