W. D. Workman Jr.

William Douglas Workman Jr., known as W. D. Workman Jr. (August 10, 1914 – November 23, 1990), was a journalist, author, and a pioneer in the development of the 20th century South Carolina Republican Party. He carried his party's banner as a candidate for the United States Senate in 1962 and for the governorship in 1982. He lost to the Democrats, Olin D. Johnston and Richard Riley, respectively.

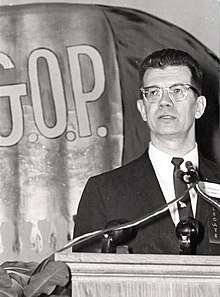

W. D. Workman Jr. | |

|---|---|

Workman in 1962 | |

| Born | August 10, 1914 |

| Died | November 23, 1990 (aged 76) Greenville, South Carolina, US |

| Resting place | Greenlawn Memorial Park in Columbia |

| Alma mater | The Citadel |

| Occupation | Journalist |

| Employer |

|

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Heber Rhea Thomas Workman (married 1939–1988, her death) |

| Children | 2, including William Douglas "Bill" Workman, III |

Background

Workman was born in Greenwood in Greenwood County in western South Carolina to W. D. Workman Sr. (1889-1957), a veteran of the United States Army during World War I, known as "Major" Workman and thereafter an educator, lawyer and a real estate agent in Greenville in Greenville County. The senior Workman served on the staff of Democratic Governor Robert Archer Cooper. Workman's mother, the former Vivian Virginia Watkins (1889–1981), was the daughter of J. Newt Watkins and a niece of a U.S. District Court judge, H. H. Watkins. Workman had a sister, Vivian Virginia Workman.[1]

Though sources say that Workman Jr. was born in Greenwood, fifty-four miles south of Greenville, it appears that Workman Sr., though born in Charleston lived after 1914 in Greenville. Therefore, it may be that Workman Jr. was also born in Greenville, rather than Greenwood, or he may have been born in Greenwood and was moved to Greenville before he was a year old.[1]

In 1931, Workman graduated from Greenville High School in Greenville. Like his father and his son as well, the junior Workman graduated in 1935 from The Citadel in Charleston. He majored in English and History. He became not a lawyer, though he did briefly study at George Washington Law School in Washington, D.C., but a newspaper journalist and also managed local radio station WTMA AM in Charleston. In 1940, the U.S. Army called Workman to active duty. He became an intelligence officer, with domestic and then foreign duty in Great Britain, the North Africa, and the Pacific Theater of Operations. After his demobilization in 1945, Workman remained in the United States Army Reserves, from which he retired twenty years later with the rank of colonel.[2]

After his World War II service, Workman returned to South Carolina to work for the Charleston News and Courier at $50 per week. He later moved to The State in the capital city of Columbia. Workman wrote columns and articles for Newsweek magazine, the Hall syndicate, and South Carolina Magazine. He appeared regularly on radio and WIS, the NBC television outlet in Columbia, to deliver political commentary.[2] He engaged in public speaking, charging $25 plus expenses for his appearances during the 1950s.[3]

Political life

Workman entered politics as a Republican challenger to Senator Olin Johnston in the general election held on November 6, 1962. He announced his campaign in December 1961, the year the South Carolina GOP elected its first member to the state House of Representatives. The Workman campaign was managed by business entrepreneur Drake Edens, sometimes considered the "father" of the modern Republican Party in South Carolina. The election occurred eleven months later, not long after the Cuban missile crisis bolstered Democratic prospects nationwide. In that same year, national attention was focused upon Richard M. Nixon, who lost his bid for governor of California to the incumbent Democrat Edmund G. Brown Sr. Workman claimed that his opponent, Senator Johnston, was too closely tied to the national party, headed by U.S. President John F. Kennedy, who had narrowly won the electoral vote of South Carolina in the 1960 race against Nixon. Workman said that he, unlike Johnston, represented the "conservative traditions" of the state. Workman's campaign was the first significant Republican effort in South Carolina since Reconstruction. Two years later in 1964, U.S. Senator Strom Thurmond endorsed Barry Goldwater for President and at the same time defected from the Democratic Party to become the first Republican state officeholder in South Carolina. Thurmond would serve for more than thirty-six years as a GOP senator plus his twelve earlier years as a Democrat.

In the campaign, Workman said:

It is the Republican Party which offers the best hope, and perhaps the last hope, of stemming the liberal tide which has been sweeping the United States toward the murky depths of socialism. ... We must stop floating along the stream of least resistance and get our feet back down on the firm ground of sound, conservative, responsible government.[2]

Workman finished with 133,390 votes (42.8 percent); Johnston, 178,712 (57.2 percent).[4] In the same 1962 election, James D. Martin of Alabama made an even stronger showing than did Workman in Martin's bid to unseat another entrenched Democratic senator, Lister Hill.

Johnston did not complete the final term to which he was elected. He died in office in 1965 and was succeeded by Governor Donald S. Russell, who resigned as governor and was appointed to the Senate by his gubernatorial successor, Robert Evander McNair. Russell was then unseated in the 1966 Democratic primary by former Governor Ernest Hollings. Workman did not run in the special election to finish Johnston's term held on November 8, 1966; instead the Republican State Senator Marshall Parker waged a strong but losing campaign against Hollings, who in effect became Johnston's long-term Senate successor.

After the 1962 campaign, Workman returned to The State, where he was assistant editor and then editor, in which capacity he became restless with the administrative duties of that position.[2] In 1970, The State endorsed the Democrat John C. West for governor, rather than the Thurmond-backed Republican, U.S. Representative Albert Watson of South Carolina's 2nd congressional district. Workman wrote that West, at the time the lieutenant governor, "had articulated a far more specific platform than any of his rivals - at least with respect to state issues" but questioned West's "ill-defined" position regarding revenues for promised teacher pay increases. Workman also advocated the election of more Republicans to the legislature during a West administration.[5]

After six years as editor, Workman in 1972 relinquished those duties to spend more time in research and writing. He remained with The State as an editorial analyst until his retirement in 1979, when he returned to Greenville.[2]

Workman ran for governor in 1982. He first scored an easy primary victory for the Republican nomination over Roddy T. Martin. Drake Edens, who drowned later in the year, urged the 68-year-old Workman not to make the gubernatorial race.[2] Workman was badly beaten the general election held on November 2, 1982, by the incumbent Democrat Richard Riley, the first South Carolina governor allowed to succeed himself without first sitting out a four-year term. Riley received 468,819 votes (69.8 percent) to Workman's 202,806 (30.2 percent).[6]

In a speech after the election, Workman said, "I'm glad I made the fight. I've opened South Carolina to a lot of truisms. One is the need for a two-party system. It would have been a fluke if I had won. All the cards were stacked against me, financial and name recognition."[2][7]

Books

In addition to his extensive career in newspaper and radio journalism, Workman wrote five non-fiction books, all of which advocated segregation.

- The Case for the South (1960) argues for segregation in the American South.

- The Bishop from Barnwell (1963) is a biography of the South Carolina State Senator Edgar Allan Brown, who unexpectedly lost the 1954 U.S. Senate race to write-in candidate Strom Thurmond.

- This Is the South (1959), edited by Robert West Howard, contains Workman's essay, "The Trailmakers."

- With All Deliberate Speed (1957), a title taken from the United States Supreme Court decision on school desegregation attempts to refute the decision.

- Southern Schools: Progress and Problems (1959), argues against school integration[2]

Personal life

In the middle 1950s, Workman, a Southern Baptist at the time, and his wife, the former Heber Rhea Thomas (1918-1988), whom he called "Tommie" and an ardent Methodist, were founding members of the Trenholm Road Methodist Church in Columbia. Workman grew disillusioned with his new denomination in areas of political and social matters,[3] particularly after it was renamed "United Methodist". In a 1972 letter to The Methodist Advocate, Workman explained his resignation as a delegate to the Southeastern Jurisdictional Conference of the United Methodist Church: "The actions and pronouncements at the 1972 General Conference make it impossible for me to profess adherence to the prevailing course of present-day Methodism. ... The church so blatantly repudiated United States policy in national and international affairs as to grievously offend my sense of loyalty to country. ..."[2] In a related letter, Workman expressed disenchantment with the church: "I fear that the magnitude and the momentum of liberal extremism in the United Methodist Church have reached the point of no return."[2]

From 1972 to 1985, Workman was the president of the James F. Byrnes Foundation. Established in 1948 by the late James F. Byrnes and his wife, Maude, the foundation provides college scholarship funds and guidance counseling for qualified orphans in South Carolina orphans.[2]

Prior to his gubernatorial race, Workman had already contracted Parkinson's disease. As the disease progressed, he died in 1990, two years after the passing of his wife, a graduate of Winthrop College and the University of South Carolina and an English professor from 1957 to 1977 at Columbia College. The couple had a son, William D. "Bill" Workman, III, a former newspaper editor, the mayor of Greenville from 1983 to 1995, and an economic development specialist, and a daughter, Dorrill Dee Workman, and four grandchildren.[2]

W. D. and his wife, Dr. H. Rhea Workman are interred at Greenlawn Memorial Park in Columbia, South Carolina. William Sr. and Vivian Workman are interred at Springwood Cemetery in Greenville.

References

- "William Douglas Workman, 1889-1957; A Register of His Papers, 1926–1956" (PDF). media.clemson.edu. Retrieved May 13, 2014.

- "W. D. Workman Papers". library.sc.edu. Retrieved May 13, 2014.

- "J. Russell Hawkins, Religion, Race, and Resistance: White Evangelicals and the Dilemma of Integration in South Carolina, 1950-1975" (PDF). Rice University dissertation, Houston, Texas. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

- Congressional Quarterly's Guide to U.S. Elections, U.S. Senate, 1962

- Billy Hathorn, "The Changing Politics of Race: Congressman Albert William Watson and the South Carolina Republican Party, 1965-1970", South Carolina Historical Magazine Vol. 89 (October 1988), p. 235

- Congressional Quarterly's Guide to U.S. Elections, Governors, 1982

- Richard Riley was later the secretary of education under President William Jefferson "Bill" Clinton, who was defeated in South Carolina in both 1992 and 1996.

External links

| Party political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Leon P. Crawford (1956) |

Republican nominee for U.S. Senator from South Carolina

William Douglas Workman Jr. |

Succeeded by Marshall Parker (1966 special election) |

| Preceded by Edward Lunn Young (1978) |

Republican nominee for governor of South Carolina

William Douglas Workman Jr. |

Succeeded by Carroll A. Campbell (1986) |