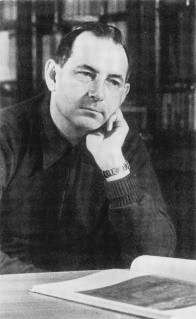

Vsevolod Kochetov

Vsevolod Anissimovich Kochetov (Russian: Все́волод Ани́симович Ко́четов) (4 February [O.S. 22 January] 1912, Novgorod, Russian Empire - 4 November 1973, Moscow) was a Soviet Russian writer and cultural functionary. He has been described as a party dogmatist[1] and as a classic of socialist realism. Some of his writings were not well received by the official press, as Kochetov was considered too "reactionary" even by Soviet standards of the 1960s.

Vsevolod Anissimovich Kochetov | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Всеволод Анисимович Кочетов 4 February 1912 Novgorod, Russian Empire |

| Died | 4 November 1973 (aged 61) Moscow, Russian SFSR, USSR |

| Occupation | Agronomist, Journalist, Novelist, Editor |

| Language | Russian |

| Nationality | Soviet |

| Education | Technical school |

| Notable works | The Zhurbin Family Brothers Yershov What Do You Want Then? |

| Notable awards | Order of Lenin |

Biography

Kochetov was born into a peasant family, the youngest of eight children, all but three of whom died of hunger or illness during the First World War.[2] His impoverished parents were unable to care for him, and he left home in 1927, moving from Novgorod to Leningrad, where he graduated in 1931 from a technical school and worked thereafter as an agronomist, then as director of a Machine Tractor Station and of a state farm.[3] In 1938 he became a reporter for the newspaper Leningradskaya Pravda. During the Second World War, Kochetov worked as a reporter for various newspapers at the Leningrad Front.

From 1946, he devoted himself to literary activities. (On the Plains of the Neva («На невских равнинах»), described recollections of the war. His writings were characterized from the start with rigorous following of the political line. In 1952 he published the novel The Zhurbin Family («Журбины»), which portrays the life of a worker dynasty. It was adapted as the film A Big Family. The book was re-published numerous times and translated into a number of languages.

His next novel, The Brothers Yershov, was composed as a sort of counterpoint to Vladimir Dudintsev’s Not by Bread Alone, but was criticized even in Pravda for exaggerations.[4] His last important work was the novel What Do You Want Then? («Чего же ты хочешь?»).

As a pro-Soviet figure, Kochetov worked for numerous years as a cultural functionary and maintained a militant communist attitude, always wary of liberal or pro-Western influences. For example, when Ilya Ehrenburg's memoirs were published, Kochetov complained of certain writers "burrowing in the rubbish heaps of their crackpot memories."[5]

As a bureaucrat, on the other hand, he managed to help his colleagues in need, including those he strongly disagreed with [6] . Kochetov was awarded a number of awards (Order of Lenin etc.). From 1955 to 1959 he was the editor in chief of Literaturnaya Gazeta, from 1961 editor in chief of the Oktyabr magazine,[7] which was in effect the conservative counterpart to Tvardovsky's Novyy Mir, a more liberal journal that published texts of dissident authors like Solzhenitsyn.

In the novel What Do You Want Then?, Kochetov treats mercilessly phenomena that he had always opposed and criticized. The novel has been compared with a pamphlet. The author rejects the values of the Western world, criticizes ‘bourgeois propaganda‘, the alleged lack of vigilance among the Soviet people, that enables the class enemies and Western "imperialists" to further their goal of undermining socialism. The plot includes a number of disguised Western agents, including а former SS man, who have been sent to the USSR to pursue subversive activities and "corrupt" the Soviet youth. The novel was not well received by Pravda and was never again published in Russia. Twenty Soviet intellectuals signed a letter of protest against the publication of such an "obscurantist" work.[8] Kochetov intended the novel as a Soviet version of The Possessed.[9]

A number of parodies of the novel were written by Russian intellectuals and circulated in samizdat), e.g. «Чего же ты хохочешь?» (Why Are You Laughing Then?), which alludes to the novel The Brothers Yershov (in that text referred to as The Brothers Yezhov).

Kochetov apparently committed suicide in 1973, as pains caused by cancer became intolerable. It is sometimes noted that his stoic, manly decision actually reconciled him with some of his opponents of his lifetime.[10]

Patricia Blake wrote of her 1962 interview with him:

In appearance, Kochetov is anything but the rough-and-ready proletarian his novels evoke. Except for his unpleasantly thin lips, he is a handsome man with fine features and a slim figure. He was impeccably dressed in a business-like dark suit, white shirt, and striped tie. ...

Kochetov was eager to talk but evidently wished to say nothing. Never before had I met a man so composed in the face of disagreeable questions, and so adroit at parrying them. ... Here, clearly was a profoundly embittered man. When he spoke about his early life I began to sense the private passions engaged in his battle against the new intelligentsia. ... Kochetov made it the hard way, and his novels are paeans to the proletariat, to men of his own experience. What can such a man feel about the young writers who have recently risen to fame by way of no harder school than the Gorky Literary Institute? I put it to him, and he replied: 'This one writes rubbish . . . that one has no ideas . . . he is also a fraud . . . not worth speaking about.' ...

We shook hands in the corridor, and he put his hand on my shoulder and said, 'You see, I'm not quite so bad as you imagined, am I? Please tell your readers that I don't eat people, that I don't swallow babies in one gulp!'[11]

Works

- On the Plains of the Neva («На невских равнинах»)

- The Zhurbin Family («Журбины», 1952)

- The Brothers Yershov (1958)

- What Do You Want Then? («Чего же ты хочешь?»)

Footnotes

- Robert H. Stacy, Russian Literary Criticism: A Short History, p. 222.

- Patricia Blake, Half-Way to the Moon: New Writing from Russia (Anchor Books, 1965), p. xxxv.

- Blake, Half-Way to the Moon, p. xxxv.

- «Правда», 1958, 25 сентября

- Stacy, Russian Literary Criticism: A Short History, p. 222.

- http://www.interlit2001.com/guerchik-st-1.htm

- Shimon Markish, "The Role of Officially Published Russian Literature in the Reevalution of Jewish National Consciousness (1953-1970)" in Yaacov Ro'i and Avi Beker, Jewish Culture and Identity in the Soviet Union (NYU Press, 1992: ISBN 0-8147-7432-6), p. 226.

- Диссидентская активность

- Павел Басинский, "Чего же ты хочешь?."

- Михаил Герчик, Халява

- Blake, Half-Way to the Moon, pp. xxxiii-xxxv[.

References

- Joseph William Augustyn, Vsevolod Kochetov: A Paragon of Literary Conservatism (Brown University Press, 1971).