Vrahovice

Vrahovice is a village in the Olomouc Region of the Czech Republic, near Prostějov, founded in 1337. It is one of the seven administrative divisions of the city of Prostějov, with a population of 3,402 inhabitants, according to the 2001 census.

Vrahovice | |

|---|---|

Saint Bartholomew's Church | |

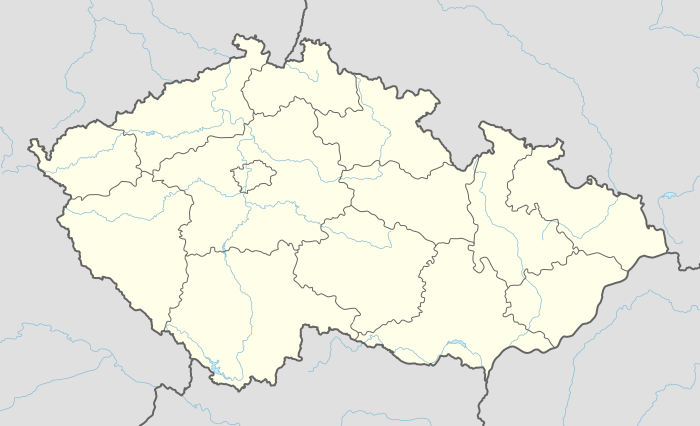

Vrahovice Location in the Czech Republic | |

| Coordinates: 49°28′51″N 17°08′54″E | |

| Country | Czech Republic |

| Region | Olomouc |

| District | Prostějov |

| Municipality | Prostějov |

| Area | |

| • Total | 6.22 km2 (2.40 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 215 m (705 ft) |

| Population (2001) | |

| • Total | 3,402 |

| • Density | 550/km2 (1,400/sq mi) |

| Time zone | CET |

| • Summer (DST) | + 1 |

| Postal code | 798 11 |

| Area code(s) | (+420) 582 |

| Website | http://www.vrahovice.eu/ |

Geography

Vrahovice lies in the Hornomoravský úval. The rivers Romže, Hloučela and Valová flow through Vrahovice. The highest point in Vrahovice is Vrbatecký kopec (known locally as Vrbák).

History

The village was first mentioned in 1337. The first mention of a church in Vrahovice was in 1370. The church was destroyed in a large fire in 1587. A church constructed shortly after the fire was used until it was destroyed in 1831. A replacement church was built between 1831 and 1836 and financed by Jan Josef Count Seilern, the owner of the Kralice domain.

A village by the name of Trpenovice (now known as Trpinky), with a written history dating back to 1349, was combined with Vrahovice in 1466.[1] From 1960–1973, Vrahovice also included the village of Čechůvky.

Through its history, Vrahovice has passed through the hands of several owners. In 1725, Jan Bedrich Seilern bought Vrahovice, and the Seilern family became the last to possess the village.

The first mayor of Vrahovice was Jan Frébort, who took office in 1848. The village experienced significant development during the interwar period, during the tenure of mayor Josef Stříž, when roads to Prostějov and Vrbátky and a new city hall were built. During World War II, occupying Nazi forces built an observation point on the hill above Vrahovice to monitor the railway. After World War II, there was an internment camp in the village for Germans from the Prostějov region awaiting transfer to Germany.[2]

Between 1950 and 1954, and from 1973 until the present day, Vrahovice has been a part of Prostějov.[3][4] Since the 1990s there have been advocates for its separation.[5][6][7]

On 9 December 2004, five people were killed in the village when a truck carrying soldiers crashed into a train.[8]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1869 | 767 | — |

| 1880 | 753 | −1.8% |

| 1890 | 775 | +2.9% |

| 1900 | 955 | +23.2% |

| 1910 | 1,352 | +41.6% |

| 1921 | 1,536 | +13.6% |

| 1930 | 1,760 | +14.6% |

| 1950 | 2,783 | +58.1% |

| 1961 | 2,897 | +4.1% |

| 1970 | 2,571 | −11.3% |

| 1980 | 3,321 | +29.2% |

| 1991 | 3,307 | −0.4% |

| 2001 | 3,402 | +2.9% |

| 2011 | 3,330 | −2.1% |

Vrahovice today

Notable buildings

The village has a church, Saint Bartholomew's, dating from the 19th century.[9] Other important local buildings include a monument to the Czechoslovak Legions, an 18th-century Roman Catholic vicarage, an 18th-century statue of Saint Florian, and a brick factory built at the beginning of the 20th century.[10]

Infrastructure

Vrahovice has a common integrated transport system with Prostějov. Bus routes from Prostějov to Přerov and Tovačov run through the village. Vrahovice is located on the train route from Nezamyslice to Olomouc. The village train station was built in 1946.

The village has a primary school dating back to the 19th century.

Community life

Vrahovice is home to a Sokol branch, a volunteer fire department, and Spolek za staré Vrahovice, an association dedicated to local history research, environmental protection, and the promotion of the village.[11] The association has renamed several streets in the village after important Vrahovice inhabitants, including Josef Stříž, František Kopečný and Zdeněk Tylšar,[12] and has created a new park, the Arboretum Vrahovice.[13][14]

There are no professional sports teams in Vrahovice. In 1930, a football team, SK Vrahovice, was established, but after the 1948 communist coup d'état, the team was banned. Its players became members of another voluntary football association, Sokol Vrahovice, which is still in existence.

In 2012, an amateur dragonboat team, Vrahovická sací jednotka, was established.

Notable residents

Musicians Zdeněk Tylšar and Bedřich Tylšar were born in the village, and linguist František Kopečný lived there for many years. Football player Rostislav Václavíček was born in Vrahovice and played football for the local team at the beginning of his career.

Other notable natives:

- Arnošt Faltýnek – actor

- Jiří Frébort – deputy of "revolutionary" Moravian parliament in 1848[15]

- Josef Šimoník – chemist

- Miloš Vymazal – optician and former associate professor at Palacký University in Olomouc

In popular culture

Jiří Bigas wrote a book, Vrahovice 119, about a village in the Sudetenland after the Second World War. He said he named the book Vrahovice because he knew the village from his childhood.[16]

Notes

- Janoušek, Vojtěch (1938). Vlastivěda moravská. Dějiny Prostějova. Prostějovský okres (in Czech). Brno. p. 259.

- Pořízková, Hana, Odsun Němců z Prostějovska (PDF) (in Czech)

- Prostějov. Dějiny města (in Czech). 2. 1999. p. 158.

- Prostějov. Dějiny města (in Czech). 2. 1999. p. 164.

- "Vrahovičtí se chtějí oddělit od Prostějova". Prostějovský týden (in Czech). 26 March 1997.

- "Lidé z okrajových částí naříkají na nezájem města". Prostějovský týden (in Czech). 8. 1999. p. 3.

- Doležalová, Marie (1999). "Proč zanikají Vrahovice?". Prostějovský týden (in Czech). 37. p. 9.

- "Při srážce s rychlíkem zemřelo pět vojáků". iDnes.cz. 8 December 2004. Archived from the original on 17 August 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- Slavné stavby Prostějova (in Czech). Prague. 2009. pp. 74–76.

- Industrální topografie. Olomoucký kraj (in Czech). Prague. 2013. p. 155. ISBN 978-80-01-05230-3.

- Ševčíková, Eva (April 4, 2005), "Vlastní pohlednicí se mohou už dnes pochlubit Vrahovice", Prostějovský den, p. 4

- Zaoral, Martin (September 21, 2010), "Prostějov pokřtí deset nových ulic", Prostějovský deník, p. 3

- Hájek, Martin (11 February 2013), "Spolek za staré Vrahovice letos slaví deset let", Prostějovský večerník, p. 15, retrieved February 21, 2013

- Masaříková, Hana (9 January 2015), "Věděli jste, že Vrahovice mají vlastní arboretum? Roste v něm i kysloun", Prostějovský deník, retrieved 10 January 2015

- Bartková, Hana (2007). "Revoluční poslanec Jiří Frébort (1807–1883)". Střední Morava (in Czech). 25: 130–132.

- Malenovský, Martin. "Vrahovice jsem psal jako ránu pěstí do nosu". Deník Referendum. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

Bibliography

- Československý sborník a almanach. Politický okres Prostějov. Olomouc 1932, pg. 79–82.

- FAKTOR, František: Popis okresního hejtmanství prostějovského. Praha 1898, pg. 109–112.

- HÁJEK, Martin: Vrahovice v moderní době. Dějiny obce v letech 1885–1973. Vrahovice 2019.

- Historický místopis Moravy a Slezska 1848–1960. Svazek 5. Ostrava 1976, pg. 71–72.

- HOSÁK, Ladislav, ŠRÁMEK, Rudolf: Místní jména na Moravě a ve Slezsku II. M–Ž. Praha 1980, pg. 740–741.

- JANOUŠEK, Vojtěch: Vlastivěda moravská. Dějiny Prostějova. Prostějovský okres. Brno 1938, pg. 251–260.

- ODLOŽIL, Pavel, ODLOŽILOVÁ, Milena: Vrahovice. Přírodní poměry, historie a současnost. Vrahovice 1993.

- Prostějov. Dějiny města I. Prostějov 2000, pg. 259–266.

- PŘÍVAL, Vojtěch a red.: Prostějovsko za války. Vzpomínky a dokumenty z let 1939–1945. Prostějov 1948, pg. 164–167.

- SCHWOY, Franz Josef: Topographie vom Markgrafthum Mähren. Band 1: Olmützer Kreis. Wien 1793, pg. 503–504.

- WOLNY, Gregor: Kirchliche Topographie von Mähren meist nach Urkunden und Handschriften. Abtheilung 1: Olmüzer Erzdiöcese: Band 1. Brünn 1855, pg. 405–408.

- WOLNY, Gregor: Die Markgraftschaft Mähren, topographisch, statistisch und historisch geschildert. V. Band. Olmützer Kreis. Brünn 1839, pg. 536–537.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vrahovice. |