Joost van den Vondel

Joost van den Vondel (Dutch: [ˈjoːst fɑn dɛn ˈvɔndəl];[1] 17 November 1587 – 5 February 1679) was a Dutch poet, writer and playwright. He is considered the most prominent Dutch poet and playwright of the 17th century. His plays are the ones from that period that are still most frequently performed, and his epic Joannes de Boetgezant (1662), on the life of John the Baptist, has been called the greatest Dutch epic.[2]

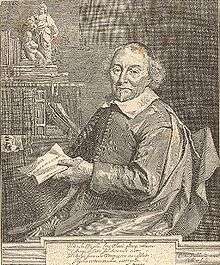

Joost van den Vondel | |

|---|---|

Joost van den Vondel by Philip de Koninck (1665) | |

| Born | 17 November 1587 Cologne, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 5 February 1679 (aged 91) Amsterdam, Dutch Republic |

| Occupation | Writer, playwright |

| Period | Dutch Golden Age |

| Spouse | Mayken de Wolff |

| Children | 4 children |

| Signature | |

Vondel's theatrical works were regularly performed until the 1960s. The most visible was the annual performance, on New Year's Day from 1637 to 1968, of Gijsbrecht van Aemstel.

Vondel remained productive until a very old age. Several of his most notable plays like Lucifer (play) and Adam in Exile were written after 1650, when he was already 65, and his final play Noah (play), written at the age of eighty, is considered one of his finest.

Biography

Vondel was born on 17 November 1587 on the Große Witschgasse in Cologne, Holy Roman Empire. His parents were Mennonites of Antwerpian descent. In 1595, probably because of their religious conviction, they fled to Utrecht, and from there, they eventually moved to Amsterdam in the newly formed Dutch Republic.

At the age of 23, Vondel married Mayken de Wolff. Together they had four children, of whom two died in infancy. After the death of his father in 1608, Vondel managed the family hosiery shop on the Warmoesstraat in Amsterdam. In the meantime, he began to learn Latin and became acquainted with famous poets such as Roemer Visscher.

Around the year 1641, he converted to Catholicism. This was a great shock to most of his fellow countrymen because the main faith and de facto state religion in the Republic was Calvinist Protestantism. It is still unclear why he became a Catholic although his love for a Catholic woman may have played a role in this (Mayken de Wolff had died in 1635).

During his life, he became one of the main advocates for religious tolerance. After the arrest, trial and the immediate beheading of the most important civilian leader of the States of the Netherlands, Johan van Oldenbarnevelt (1619), at the command of his enemy, Prince Maurits of Nassau, and the Synod of Dort (1618–1619), the Calvinists became the decisive religious power in the Republic. Public practice of Catholicism, Anabaptism and Arminianism was from then on officially forbidden but worship in clandestine houses of prayer was tolerated. Vondel wrote many satires criticising the Calvinists and extolling Oldenbarnevelt. That, together with his new faith, made him an unpopular figure in Calvinist circles. He died a bitter man though he was honoured by many fellow poets, on 5 February 1679.

George Borrow called him "by far the greatest [man] that Holland ever produced."[3]

Plays

His plays included:

- The Passover or the Redemption of Israel from Egypt (1610),

- Jerusalem Destroyed (1620),

- Palamedes (1625),

- Hecuba (1626),

- Joseph (1635),

- Gijsbrecht van Aemstel (1637),

- The Maidens (1639),

- The Brothers (1640),

- Joseph in Dothan (1640),

- Joseph in Egypt (1640),

- Peter and Paul (1641),

- Mary Stuart or Tortured Majesty (1646),

- Lion Fallers (1647),

- Solomon (1648),

- Lucifer (1654),

- Salmoneus (1657),

- Jephthah (1659),

- David in Exile (1660),

- David Restored (1660),

- Samson or Holy Revenge (1660),

- The Sigh of Adonis (1661),

- The Batavian Brothers or Oppressed Freedom (1663),

- Phaeton (1663),

- Adam in Exile from Eden (1664),

- The Destruction of the Sinai Army (1667),

- Noah and the Fall of the First World (1667).

Lucifer (1654) and Milton's Paradise Lost

It has been suggested[4] that John Milton drew inspiration from Lucifer (1654) and Adam in Ballingschap (1664) for his Paradise Lost (1667). In some respects the two works have similarities: the focus on Lucifer, the description of the battle in heaven between Lucifer's forces and Michael's, and the anti-climax as Adam and Eve leave Paradise.

One example of similarity is the following:

"Here may we reign secure, and in my choice To reign is worth ambition, though in Hell.

Better to reign in hell than serve in heaven."

- Milton's Paradise Lost

"Is ’t noodlot, dat ick vall’, van eere en staet berooft,

Laet vallen, als ick vall’, met deze kroone op ’t hooft,

Dien scepter in de vuist, dien eersleip van vertrouden,

En zoo veel duizenden als onze zyde houden.

Dat valle streckt tot eer, en onverwelckbren lof:

En liever d’ eerste Vorst in eenigh laeger hof,

Dan in ’t gezalight licht de tweede, of noch een minder

Zoo troost ick my de kans, en vrees nu leet noch hinder."

Translation:

Is it fate that I will fall, robbed of honour and dignity,

Then let me fall, if I were to fall, with this crown upon my head

This sceptre in my fist, this company of loyals,

And as many as are loyal to our side.

This fall would honour one, and give unwilting praise:

And rather [would I be] foremost king in any lower court,

Than rank second in most holy light, or even less

Thus I justify my revolt, and will not fear pain nor hindrance.

- Vondel's Lucifer

Commemoration

Amsterdam's biggest park, the Vondelpark, bears his name. There is a statue of Vondel in the northern part of the park. Also, there is a Vondel Street in Cologne, the Vondelstraße in the Neustadt-Süd-district.

The Dutch five guilder banknote bore Vondel's portrait from 1950 until it was discontinued in 1990.

References

- Van in isolation: [vɑn].

- Guerber, H. A. (1913). The Book of the Epic. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott. p. 356.

- George Borrow, Wild Wales, p. 105.

- Cf. George Edmundson, Milton and Vondel: a curiosity of literature, London: 1885.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Joost van den Vondel. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Works by Joost van den Vondel at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Joost van den Vondel at Internet Archive

- Reinder P. Meijer (1978). "The golden age – Seventeenth century". Literature of the Low Countries.

- (in Dutch) Joost van den Vondel at the Project Laurens Janszoon Coster

- (in Dutch) Joost van den Vondel at the Digital library for Dutch literature

- (in Dutch) Joost van den Vondel: Profiel at the National Library of the Netherlands

- (in Dutch) Complete digitized copy of Lucifer, 1654