Von Neumann universe

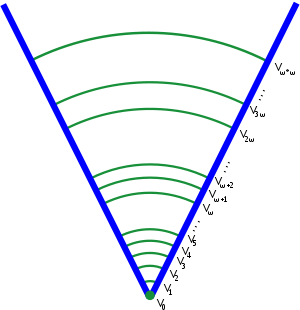

In set theory and related branches of mathematics, the von Neumann universe, or von Neumann hierarchy of sets, denoted V, is the class of hereditary well-founded sets. This collection, which is formalized by Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory (ZFC), is often used to provide an interpretation or motivation of the axioms of ZFC.

The rank of a well-founded set is defined inductively as the smallest ordinal number greater than the ranks of all members of the set.[1] In particular, the rank of the empty set is zero, and every ordinal has a rank equal to itself. The sets in V are divided into the transfinite hierarchy Vα , called the cumulative hierarchy, based on their rank.

Definition

The cumulative hierarchy is a collection of sets Vα indexed by the class of ordinal numbers; in particular, Vα is the set of all sets having ranks less than α. Thus there is one set Vα for each ordinal number α. Vα may be defined by transfinite recursion as follows:

- Let V0 be the empty set:

- For any ordinal number β, let Vβ+1 be the power set of Vβ:

- For any limit ordinal λ, let Vλ be the union of all the V-stages so far:

A crucial fact about this definition is that there is a single formula φ(α,x) in the language of ZFC that defines "the set x is in Vα".

The sets Vα are called stages or ranks.

The class V is defined to be the union of all the V-stages:

An equivalent definition sets

for each ordinal α, where is the powerset of .

The rank of a set S is the smallest α such that Another way to calculate rank is:

- .

Finite and low cardinality stages of the hierarchy

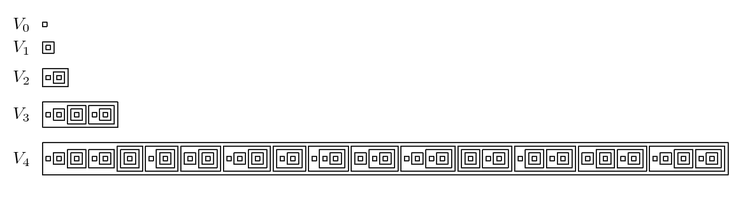

The first five von Neumann stages V0 to V4 may be visualized as follows. (An empty box represents the empty set. A box containing only an empty box represents the set containing only the empty set, and so forth.)

The set V5 contains 216 = 65536 elements. The set V6 contains 265536 elements, which very substantially exceeds the number of atoms in the known universe. So the finite stages of the cumulative hierarchy cannot be written down explicitly after stage 5. The set Vω has the same cardinality as ω. The set Vω+1 has the same cardinality as the set of real numbers.

Applications and interpretations

Applications of V as models for set theories

If ω is the set of natural numbers, then Vω is the set of hereditarily finite sets, which is a model of set theory without the axiom of infinity.[2][3]

Vω+ω is the universe of "ordinary mathematics", and is a model of Zermelo set theory.[4] A simple argument in favour of the adequacy of Vω+ω is the observation that Vω+1 is adequate for the integers, while Vω+2 is adequate for the real numbers, and most other normal mathematics can be built as relations of various kinds from these sets without needing the axiom of replacement to go outside Vω+ω.

If κ is an inaccessible cardinal, then Vκ is a model of Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory (ZFC) itself, and Vκ+1 is a model of Morse–Kelley set theory.[5][6] (Note that every ZFC model is also a ZF model, and every ZF model is also a Z model.)

Interpretation of V as the "set of all sets"

V is not "the set of all sets" for two reasons. First, it is not a set; although each individual stage Vα is a set, their union V is a proper class. Second, the sets in V are only the well-founded sets. The axiom of foundation (or regularity) demands that every set be well founded and hence in V, and thus in ZFC every set is in V. But other axiom systems may omit the axiom of foundation or replace it by a strong negation (an example is Aczel's anti-foundation axiom). These non-well-founded set theories are not commonly employed, but are still possible to study.

A third objection to the "set of all sets" interpretation is that not all sets are necessarily "pure sets", which are constructed from the empty set using power sets and unions. Zermelo proposed in 1908 the inclusion of urelements, from which he constructed a transfinite recursive hierarchy in 1930.[7] Such urelements are used extensively in model theory, particularly in Fraenkel-Mostowski models.[8]

V and the axiom of regularity

The formula V = ⋃αVα is often considered to be a theorem, not a definition.[9][10] Roitman states (without references) that the realization that the axiom of regularity is equivalent to the equality of the universe of ZF sets to the cumulative hierarchy is due to von Neumann.[11]

The existential status of V

Since the class V may be considered to be the arena for most of mathematics, it is important to establish that it "exists" in some sense. Since existence is a difficult concept, one typically replaces the existence question with the consistency question, that is, whether the concept is free of contradictions. A major obstacle is posed by Gödel's incompleteness theorems, which effectively imply the impossibility of proving the consistency of ZF set theory in ZF set theory itself, provided that it is in fact consistent.[12]

The integrity of the von Neumann universe depends fundamentally on the integrity of the ordinal numbers, which act as the rank parameter in the construction, and the integrity of transfinite induction, by which both the ordinal numbers and the von Neumann universe are constructed. The integrity of the ordinal number construction may be said to rest upon von Neumann's 1923 and 1928 papers.[13] The integrity of the construction of V by transfinite induction may be said to have then been established in Zermelo's 1930 paper.[7]

History

The cumulative type hierarchy, also known as the von Neumann universe, is claimed by Gregory H. Moore (1982) to be inaccurately attributed to von Neumann.[14] The first publication of the von Neumann universe was by Ernst Zermelo in 1930.[7]

Existence and uniqueness of the general transfinite recursive definition of sets was demonstrated in 1928 by von Neumann for both Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory[15] and Neumann's own set theory (which later developed into NBG set theory).[16] In neither of these papers did he apply his transfinite recursive method to construct the universe of all sets. The presentations of the von Neumann universe by Bernays[9] and Mendelson[10] both give credit to von Neumann for the transfinite induction construction method, although not for its application to the construction of the universe of ordinary sets.

The notation V is not a tribute to the name of von Neumann. It was used for the universe of sets in 1889 by Peano, the letter V signifying "Verum", which he used both as a logical symbol and to denote the class of all individuals.[17] Peano's notation V was adopted also by Whitehead and Russell for the class of all sets in 1910.[18] The V notation (for the class of all sets) was not used by von Neumann in his 1920s papers about ordinal numbers and transfinite induction. Paul Cohen[19] explicitly attributes his use of the letter V (for the class of all sets) to a 1940 paper by Gödel,[20] although Gödel most likely obtained the notation from earlier sources such as Whitehead and Russell.[18]

Philosophical perspectives

There are two approaches to understanding the relationship of the von Neumann universe V to ZFC (along with many variations of each approach, and shadings between them). Roughly, formalists will tend to view V as something that flows from the ZFC axioms (for example, ZFC proves that every set is in V). On the other hand, realists are more likely to see the von Neumann hierarchy as something directly accessible to the intuition, and the axioms of ZFC as propositions for whose truth in V we can give direct intuitive arguments in natural language. A possible middle position is that the mental picture of the von Neumann hierarchy provides the ZFC axioms with a motivation (so that they are not arbitrary), but does not necessarily describe objects with real existence.

See also

Notes

- Mirimanoff 1917; Moore 2013, pp. 261–262; Rubin 1967, p. 214.

- Roitman 2011, p. 136, proves that: "Vω is a model of all of the axioms of ZFC except infinity."

- Cohen 2008, p. 54, states: "The first really interesting axiom [of ZF set theory] is the Axiom of Infinity. If we drop it, then we can take as a model for ZF the set M of all finite sets which can be built up from ∅. [...] It is clear that M will be a model for the other axioms, since none of these lead out of the class of finite sets."

- Smullyan & Fitting 2010. See page 96 for proof that Vω+ω is a Zermelo model.

- Cohen 2008, p. 80, states and justifies that if κ is strongly inaccessible, then Vκ is a model of ZF.

- "It is clear that if A is an inaccessible cardinal, then the set of all sets of rank less than A is a model for ZF, since the only two troublesome axioms, Power Set and Replacement, do not lead out of the set of cardinals less than A."

- Roitman 2011, pp. 134–135, proves that if κ is strongly inaccessible, then Vκ is a model of ZFC.

- Zermelo 1930. See particularly pages 36–40.

- Howard & Rubin 1998, pp. 175–221.

- Bernays 1991. See pages 203–209.

- Mendelson 1964. See page 202.

- Roitman 2011. See page 79.

- See article On Formally Undecidable Propositions of Principia Mathematica and Related Systems and Gödel 1931.

- von Neumann 1923, von Neumann 1928b. See also the English-language presentation of von Neumann's "general recursion theorem" by Bernays 1991, pp. 100–109.

- Moore 2013. See page 279 for the assertion of the false attribution to von Neumann. See pages 270 and 281 for the attribution to Zermelo.

- von Neumann 1928b.

- von Neumann 1928a. See pages 745–752.

- Peano 1889. See pages VIII and XI.

- Whitehead & Russell 2009. See page 229.

- Cohen 2008. See page 88.

- Gödel 1940.

References

- Bernays, Paul (1991) [1958]. Axiomatic Set Theory. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-66637-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cohen, Paul Joseph (2008) [1966]. Set theory and the continuum hypothesis. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-46921-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gödel, Kurt (1931). "Über formal unentscheidbare Sätze der Principia Mathematica und verwandter Systeme, I". Monatshefte für Mathematik und Physik. 38: 173–198.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gödel, Kurt (1940). The consistency of the axiom of choice and of the generalized continuum-hypothesis with the axioms of set theory. Annals of Mathematics Studies. 3. Princeton, N. J.: Princeton University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Howard, Paul; Rubin, Jean E. (1998). Consequences of the axiom of choice. Providence, Rhode Island: American Mathematical Society. pp. 175–221. ISBN 9780821809778.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jech, Thomas (2003). Set Theory: The Third Millennium Edition, Revised and Expanded. Springer. ISBN 3-540-44085-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kunen, Kenneth (1980). Set Theory: An Introduction to Independence Proofs. Elsevier. ISBN 0-444-86839-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Manin, Yuri I. (2010) [1977]. A Course in Mathematical Logic for Mathematicians. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. 53. Translated by Koblitz, N. (2nd ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 89–96. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0615-1. ISBN 978-144-190-6144.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mendelson, Elliott (1964). Introduction to Mathematical Logic. Van Nostrand Reinhold.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mirimanoff, Dmitry (1917). "Les antinomies de Russell et de Burali-Forti et le probleme fondamental de la theorie des ensembles". L'Enseignement Mathématique. 19: 37–52.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moore, Gregory H (2013) [1982]. Zermelo's axiom of choice: Its origins, development & influence. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-48841-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Peano, Giuseppe (1889). Arithmetices principia: nova methodo exposita. Fratres Bocca.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Roitman, Judith (2011) [1990]. Introduction to Modern Set Theory. Virginia Commonwealth University. ISBN 978-0-9824062-4-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rubin, Jean E. (1967). Set Theory for the Mathematician. San Francisco: Holden-Day. ASIN B0006BQH7S.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smullyan, Raymond M.; Fitting, Melvin (2010) [revised and corrected republication of the work originally published in 1996 by Oxford University Press, New York]. Set Theory and the Continuum Problem. Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-47484-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- von Neumann, John (1923). "Zur Einführung der transfiniten Zahlen". Acta litt. Acad. Sc. Szeged X. 1: 199–208.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link). English translation: van Heijenoort, Jean (1967), "On the introduction of transfinite numbers", From Frege to Godel: A Source Book in Mathematical Logic, 1879-1931, Harvard University Press, pp. 346–354

- von Neumann, John (1928a). "Die Axiomatisierung der Mengenlehre". Mathematische Zeitschrift. 27: 669–752. doi:10.1007/bf01171122.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- von Neumann, John (1928b). "Über die Definition durch transfinite Induktion und verwandte Fragen der allgemeinen Mengenlehre". Mathematische Annalen. 99: 373–391. doi:10.1007/bf01459102.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Whitehead, Alfred North; Russell, Bertrand (2009) [1910]. Principia Mathematica. Volume One. Merchant Books. ISBN 978-1-60386-182-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zermelo, Ernst (1930). "Über Grenzzahlen und Mengenbereiche: Neue Untersuchungen über die Grundlagen der Mengenlehre". Fundamenta Mathematicae. 16: 29–47.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)