Vladimir Krupin

Vladimir Nikolayevich Krupin (Russian: Влади́мир Никола́евич Крупи́н, September 7, 1941) is a Soviet Russian writer, editor, religious author and tutor. The major proponent of the Village prose movement, noted for his quirky, folklore-rooted style of writing, Krupin is best known for his 1980 Novy Mir-published satirical novel Zhivaya Voda (Aqua Vitae).[1]

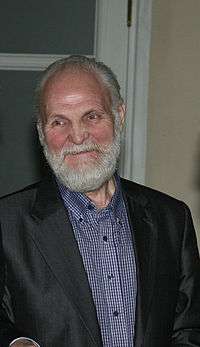

Vladimir Krupin | |

|---|---|

Vladimir Krupin in 2011 | |

| Born | September 7, 1941 Kilmez, Kirovskaya Oblast, USSR |

| Education | Krupskaya Pedagogical Institute |

| Period | 1974 - present |

| Genre | Fiction |

| Subject | Russian village Orthodoxy |

| Notable works | Aqua Vitae (1980) |

Biography

Vladimir Krupin was born in the village of Kilmez, Kirovskaya Oblast, to a local forester. In 1957, after graduating from school, he joined a local newspaper. In 1961, having demobilized from the Soviet Army, Krupin became a member of the CPSU. In 1967 he graduated from N.K.Krupskaya Moscovskaya Oblast Pedagogical Institute and spent several years teaching Russian language in schools. Krupin joined the Sovremennik Publishers as an editor and at one point became its partorg, but was fired after the publication of Georgy Vladimov's Three Minutes of Silence.[1]

In 1974 Vladimir Krupin published his first book, the collection of short stories Zyorna (Grains). That year also saw the publication of his short novels Varvara and The Yamshchik Tale. In 1980 the satirical short novel Aqua Vitae, dealing with the degradation of the Soviet rural community, steeped in mass alcoholism, made Krupin a well-known author. The publication of another novel, The 40th Day in Nash Sovremennik cost Yuri Seleznyov his post of deputy editor. In 1980-1982 Krupin edited the literary Moskva magazine. His 1980s works, notably Bokovoy veter (The Side Wind, 1982) and Povest o vom, kak... (The Tale of How..., 1985), examined hardships of life in the Soviet village.[1]

Krupin reacted to perestroika with highly politicized novels The Saving of the Perished (1988) and Good-Bye Russia, Meet You in Paradise (1991), the latter portraying the demise of rural Russia, being deliberately destroyed by the new leadership who turns the country into one psychiatric ward. Outraged by the destruction of the Russian Parliament in October 1993, he reacted by the series of articles ("The Cross and the Void", "The Bitter Grief", and others) published by Nash Sovremennik and Moskva.[1]

In 1994 Krupin started to lecture at the Moscow Religious Academy. In 1998 he became the editor-in-chief of the Orthodox Christian magazine Blagodatny Ogon' (Benevolent Fire). He is a long-standing Chairman of the Orthodox Christian film festival Radonezh.[1][2]

Selected bibliography

- Zyorna (Grains, 1974, short story collection)

- Do vecherney zvezdy (Before the Evening Star, 1977, short story collection)

- Zhivaya Voda (Aqua Vitae, 1980)

- Verbnoye voskresenye (Pussy-willow Sunday, 1981)

- Sorokovoy den' (The 40th Day, 1981)

- Vo vsyu ivanovskuyu (Full Throttle, 1985)

- Doroga Domoy (The Way Home, 1985)

- Vyatskaya tetrad (The Vyatka Notebook, 1987, short story collection)

- Prosti, proshchay (Forgive Me and Let Go, 1988)

- Kak tolko, tak srazu (Once... Then at Once, 1992)

- Krestny khod (The Procession, 1993)

- Povesti poslednego vremeni (Tales of the Later Times, 2003)

- Dymka (The Haze, 2007, collection)

References

- "Krupin, Vladimir Nikolayevich". Russian Literature of the 20th century. Bibliographical Dictionary. Vol. 2. pp. 321-324. Retrieved 2012-03-01.

- Krupin's biography at the Russian People's Line site (ruskline.ru)