Vince Coleman (train dispatcher)

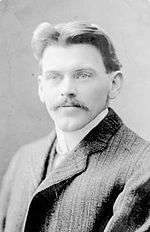

Patrick Vincent Coleman (13 March 1872 – 6 December 1917)[1] was a train dispatcher for the Canadian Government Railways (formerly the ICR, Intercolonial Railway of Canada) who was killed in the Halifax Explosion, but not before he sent a message to an incoming passenger train to stop out of range of the explosion. Today he is remembered as one of the heroic figures from the disaster.

Event

On the morning of 6 December 1917, the 45-year-old Coleman and Chief Clerk William Lovett were working in the Richmond station, surrounded by the railway yards near the foot of Richmond Street, only a few hundred feet from Pier 6. From there, trains were controlled on the main line into Halifax. The line ran along the western shore of Bedford Basin from Rockingham Station to the city's passenger terminal at the North Street Station, located a mile to the south of Richmond Station. Coleman was an experienced dispatcher who had been commended a few years earlier for helping to safely stop a runaway train.[2]

At approximately 8:45 a.m., there was a collision between SS Mont-Blanc, a French munitions ship carrying a cargo of high explosives, and a Norwegian vessel, SS Imo. Immediately thereafter Mont-Blanc caught fire, and the crew abandoned ship. The vessel drifted from near the mid-channel over to Pier 6 on the slack tide in a matter of minutes and beached herself.[3] A sailor, believed to have been sent ashore by a naval officer, warned Coleman and Lovett of her cargo of high explosives.[4] The overnight express train No. 10 from Saint John, New Brunswick, carrying nearly 300 passengers, was due to arrive at 8:55 a.m. Before leaving the office, Lovett called CGR terminal agent Henry Dustan to warn him of a burning ship laden with explosives that was heading for the pier.[5] After sending Lovett's message, Coleman and Lovett were said to have left the CGR depot. However, the dispatcher returned to the telegraph office and continued sending warning messages along the rail line as far as Truro to stop trains inbound for Halifax. An accepted version of Coleman's Morse code message reads as follows:

Hold up the train. Ammunition ship afire in harbour making for Pier 6 and will explode. Guess this will be my last message. Good-bye boys.[6]

The telegraphed warnings were apparently heeded, as the No. 10 passenger train was stopped just before the explosion occurred. The train was halted at Rockingham Station, on the western shore of Bedford Basin, approximately 6.4 kilometres (4.0 mi) from the downtown terminal. After the explosion, Coleman's message, followed by other messages later sent by railway officials who made their way to Rockingham, passed word of the disaster to the rest of Canada. The railway quickly mobilized aid, sending a dozen relief trains with fire and medical help from towns in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick on the day of the disaster, followed two days later by help from other parts of Canada and from the United States, most notably Boston. Even though Lovett had left the station, both he and Coleman were killed in the explosion.[7]

Although historians debate whether Coleman's initial message actually contributed to stopping the No. 10 train, there is some documented evidence to indicate it did. No. 10's Conductor Gillespie reported to the Moncton Transcript that although running on time, "his train was held for fifteen minutes by the dispatcher at Rockingham."[8]

Legacy

Vince Coleman was also the subject of a Heritage Minute and was a prominent character in the CBC miniseries Shattered City: The Halifax Explosion. The Heritage Minute and other sources contain historical inaccuracies in that Coleman is shown warning others in the area surrounding the depot station of the impending explosion. In reality the Richmond Station was surrounded by freight yards. Another error is the exaggeration of the number of passengers aboard the Saint John train. The four-car overnight passenger train contained a maximum of 300 people, not 700 as claimed in the Heritage Minute.[9] The warning message is also changed. Coleman's telegraph key, watch and pen are on display in the Halifax Explosion exhibit at Halifax's Maritime Museum of the Atlantic.

Coleman is interred at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Halifax, at the intersection of Mumford Road with Joseph Howe Drive. A street is named after him in the Clayton Park neighbourhood of Halifax, and in 2007 a section of Albert Street near his old home was renamed Vincent Street. A condominium near Mount Olivet Cemetery on Bayer's Road is named The Vincent Coleman, also in his honour.[10]

Coleman was inducted into the Canadian Railway Hall of Fame in 2004.[11] A Halifax harbour ferry was named Vincent Coleman, by popular vote in the spring of 2017.[12] The ferry was dedicated and officially entered service in a ceremony at the Halifax ferry terminal on March 14, 2018[13]

Personal life

Coleman was survived by his wife Frances (1875-1970), although she and the youngest of their four children were seriously injured in the explosion.[13][14]

See also

- PEPCON disaster - Roy Westerfield sacrificed himself to warn others of an imminent explosion.

Footnotes

- Nova Scotia Vital Statistics, Birth: Registration Year: 1874 - Book: 1811 - Page: 5 - Number: 92; Death: Registration Year: 1917 - Page: 102 - Number: 613

- "Dan Conlin, "Vincent Coleman and the Halifax Explosion", Maritime Museum of the Atlantic web page". Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Investigation into the Halifax Explosion, RG 42-C-3-a, vol. 596 and Appeal Book and other records, RG 42-C-3-a, vol. 597, testimony of Edward McCrossan (SS Curacas), Library and Archives Canada.

- Scapegoat, the extraordinary legal proceedings following the 1917 Halifax Explosion, Joel Zemel (2012), note 80, p. 382. The only naval officer in the vicinity of Pier 6 before and after the collision with knowledge of Mont Blanc's cargo was the port convoy officer, Lieutenant James Anderson Murray (RNCVR), aboard Hilford. The small tug was chartered by the RN's Port Convoy Office under the command of Rear-Admiral Bertram M. Chambers. According to the testimony of Francis Mackey, the pilot of Mont-Blanc (Appeals Book: Imo vs. Mont-Blanc), Hilford was close enough to Pier 6 to put a sailor ashore quickly in order to warn people about the nature of the French ship's cargo.

- Investigation into the Halifax Explosion, RG 42-C-3-a, vol. 596 and Appeal Book and other records, RG 42-C-3-a, vol. 597, testimony of Henry Dustan, Library and Archives Canada.

- "Vincent Coleman and the Halifax Explosion". Maritime Museum of the Atlantic. 6 December 1917. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Dan Conlin, "Vincent Coleman and the Halifax Explosion", Maritime Museum of the Atlantic web page Archived 16 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine; Nova Scotia Vital Statistics.

- Built for War: Canada's Intercolonial Railway, Jay Underwood (2005).

- Metson, Graham (1978). The Halifax Explosion. McGraw Hill Ryerson. p. 42.

- Power, Bill (11 January 2013). "Apartment project started". The Chronicle Herald. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- "Vince Coleman (2004)". Canadian Railway Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 15 June 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- "They've been acknowledged: Vince Coleman, Rita Joe chosen as new Halifax ferry names". Metro News. 2 June 2017. Archived from the original on 5 June 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- Bradley, Susan (14 March 2018). "He loved the railway and he loved his job': Halifax ferry dedicated to Vincent Coleman". CBC News. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "Frances Coleman". Riva Spatz Women’s Wall of Honour. Mount Saint Vincent University. Archived from the original on 9 December 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2018.