Villa Arbelaiz

Villa Arbelaiz, also called Villa Arbelaïtz, was a Belle Époque-style villa in Saint-Jean-de-Luz, Pyrénées-Atlantiques, France. It was the residence-in-exile of the Carlist politician Tirso de Olazábal y Lardizábal, Count of Arbelaiz.

The Grand Casino of Saint-Jean-de-Luz

In 1880 was built the first casino of Saint-Jean-de-Luz, known as the Grand Casino, which was an incontournable element of the new seaside resort to distract European elite that at the time settled in the commune to spend summer months. The Grand Casino was built by Victor Benquet at the limit of the commune in front of the beach. It was an edifice with 130 meters of façade and an important garden. It fell into the hands of many owners (bankers and traders from Bayonne and Bordeaux) holding an important role in the social life of the region until its bankruptcy and subsequent closure near 1895.

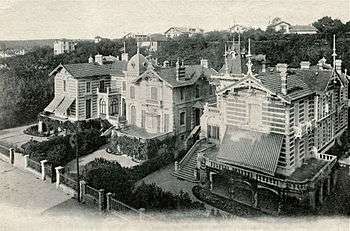

Three Villas

By the 1890s the property was purchased by Tirso de Olazábal y Lardizábal, Count of Arbelaiz, and Graziela Zileri del Verme degli Obbizi, Duchess of Cadaval. Olazábal, the Chief Deputy (Jefe Delegado) of Carlism in Vascongadas and Navarre between 1887 and 1913, had moved to Saint-Jean-de-Luz after the Carlist defeat in the Civil War, remaining there ever since and acquiring several properties in the province of Labourd. Graziela Zileri, an Italian aristocrat whose maternal grandmother was the famous Duchess of Berry,[1] was married to the Portuguese aristocrat Jaime Álvares Pereira de Melo, 8th Duke of Cadaval (branch of the House of Braganza). After the Liberal Wars, the Cadaval had fled to Spain, where they supported Carlism, and then settled in France.

The huge edifice was then divided into three Villas and the style of the front was improved. From left to right, the first Villa (the largest of the three), called Arbelaïtz, became the residence of the Counts of Arbelaiz and their ten children. The second one, called Itchola, became the residence of Tirso's son Ramón de Olazábal y Álvarez de Eulate and his Portuguese wife, Maria Luísa de Mendóça Rolim de Moura Barreto,[2] daughter of the Counts of Azambuja and granddaughter of Infanta Ana de Jesus Maria of Portugal. The third Villa, called Eguskitza, was the vacation home of the Duchess of Cadaval and her family, whose permanent residence at the time was in Pau.

Each Villa had a staircase and an independent entrance; the first two (both belonging) to the Olazábal family, had a communication to the main floor by a gallery. The second level of the building was raised, the windows were enlarged and the roofs were decorated with pinnacles and finials as well as wooden lace skirts under the eaves of the gables, in the style of a Swiss chalet, as in many villas of the Belle Époque. Villas Itchola and Esguzkitza were flanked by towers, high above the old gallery of arcades.

Residence of Tirso de Olazábal

Villa Arbelaiz owed its name to Tirso's title and the majorat (mayorazgo) of his family. With the death of his father in 1865, Tirso had inherited, among other properties located in Guipúzcoa, the Arbelaiz Palace and its formidable private garden, in Irun. This ancestral estate had remained in the hands of his family since the reign of Philip II of Spain and hosted various historical figures (Elisabeth of Valois, Henry III of France, Catherine de' Medici, Archduke Albert of Austria, Anne of Austria, Charles IV of Lorraine, Catherine of Braganza, Philip V of Spain and Charles X of France, etc.). Built in the sixteenth century by the powerful Arbelaiz family, it passed by marriage to the Olazábal family after the wedding of Tirso’s great-grandmother, the Dowager Marchioness of Valdespina, Maria Teresa de Murguía y Arbelaiz,[3] XV Lady (Señora) of Murguía and VI Lady (Señora) of Arbelaiz, with Domingo José de Olazábal y Aranzate, in 1756.

Art collection

The villa contained the art collection assembled by the Arbelaiz family since the 16th century and mainly composed of gifts received from the historical figures who stayed in the Arbelaiz Palace between 1565 and 1782. It included works attributed to Correggio, Carracci, van Dyck and Murillo, but also later acquisitions of paintings by Léon Bonnat, Eduardo Rosales, Santiago Arcos and Hubert-Denis Etcheverry. The collection also included sculpture and pieces of goldsmithery. One of its highlights was the Virgin of Abaria, an alabaster statue of the Our Lady of Mercy (Nuestra Señora de las Mercedes) dating from the second half of the seventeenth century, which was given by Charles II of Spain to the general of the Royal Army and Tirso's ancestor Don Francisco de Abaria.

Social center of Saint-Jean-de-Luz

While living in Villa Arbelaiz, Tirso de Olazábal was noted for occasional Saint-Jean-de-Luz conferences with other Carlist leaders.[4] In pieces published by Spanish press envoys he was presented, “surrounded by his family”, as sort of a local tourist attraction.[5]

During the early 1900s, Villa Arbelaiz became a centre of social life, notorious for welcoming notable personalities associated with the legitimist movement as well as close friends and relatives of the Olazábal family. Among its regular guests was Don Jaime de Borbón, who stayed there several times for more than a decade.[6] Other distinguished guests included the former Queen Natalie of Serbia, Princes and Princesses of Bourbon-Parma, Lord Ashburnham, Italian aristocrats like the Counts Zileri Dal Verme and Emo Capodilista, the Duchess of Cadaval, the Counts O'Byrne of Corville and several Legitimist politicians.

Carlist headquarters

Since the Carlist defeat in the 1872–1876 War, Olazábal had joined a committee co-ordinating Carlist activities in France.[7] As his previous residences in the area, Villa Arbelaiz turned into a Carlist émigré headquarters and Olazábal kept the conspiratorial activity that years before had led the Liberal press to consider him one of the most insatiable and dangerous exiles.[8] At least in 1905 he ventured to enter Spain, accompanying Don Jaime during his visit to Covadonga.[9] Also later he kept feeding the press with news about royal whereabouts.[10] By those years, the Spanish government demanded that the French tightly control Olazábal and his son-in-law, Julio de Urquijo e Ibarra.[11] As Paris was upset with Olazábal’s public criticism of the republican secular education system,[12] in October 1910 he was ordered to move North of the Loire;[13] his duties were taken over by Urquijo, permitted to stay in the South.[14] It was only in May 1911 that he was allowed to come back to Labourd,[15] though some sources claim he was expulsed from France in 1912.[16]

First World War

With the beginning of the First World War, the Olazábal family, regarded as close to the Austrian circles and known for its Germanophilia, found itself pressured by French public opinion. In fact, Tirso de Olazábal had kept during his years of exile close relations with the Emperor Franz Joseph, with the Count of Caserta, with the Dukes in Bavaria and other personalities with political or family connections to the imperial circles.[17] Olazábal was also a close friend of Robert of Parma - with whom he kept a regular correspondence over 30 years (particularly on hunting issues) - whose daughter, Zita, married in 1911 the Archduke Charles and became, in 1916, Empress consort of Austria. Some of his children, particularly José Joaquín, were close friends of the Bourbon-Parma family being regular guests at the Château de Chambord and at Wartegg Castle in Rorschach.

The Olazábal's circle of friends in Saint-Jean-de-Luz also included the Count John O'Byrne and his wife, Eleanor (Lory) von Hübner, daughter of the Austrian politician and diplomat Count Joseph von Hübner, himself a profound admirer of the old aristocratic regime and the last survivor of the Metternich school.

This network of relations and friendships led the Olazábal to leave France in 1915, fearing reprisals by the French authorities. They moved provisionally to San Lorenzo de El Escorial[18] and then settled permanently in San Sebastián, where Tirso remained until his death in 1921. Although the family remained in possession of Villa Arbelaiz and its other properties in the area for a few more decades, they did not return to live in Saint-Jean-de-Luz.

See also

- Tirso de Olazábal y Lardizábal

- Carlism

- Jaime III

- Saint-Jean-de-Luz

Notes

- see Graziela Zileri del Verme degli Obbizi entry at Geneall genealogical service available here

- see Maria Luísa de Mendóça Rolim de Moura Barreto entry at Geni genealogical service available here

- Antonio Gaytán de Ayala Artázcoz, Parientes mayores de Guipúzcoa: señores del palacio casa-fuerte de Murguía en Astigarraga, [in:] Revista Internacional de los Estudios Vascos, París 1934, pp. 373–375

- Agustín Fernández Escudero, El marqués de Cerralbo (1845–1922): biografía politica [PhD thesis], Madrid 2012, p. 409

- La Epoca 26.08.06, available here

- La Vanguardia 22.08.1903, available here, ABC 11.05.1912, available here, La Vanguardia 11.05.1912, available here, El Correo del Norte 14.05.1912, available here

- composed also of conde de Robres, Iturbe, Celestino Yturralde and Nemesio Latorre, Eduardo González Calleja, La razón de la fuerza: orden público, subversión y violencia política en la España de la Restauración (1875–1917), Madrid 1998, ISBN 8400077784, 9788400077785, p. 159

- El Correo Militar 30.08.88, available here

- El Imparcial 15.08.95, available here; the news was even reported in women's fashion magazine La Ultima Moda, see here

- Heraldo de Madrid 19.02.06, available here

- González Calleja 1998, p. 481

- González Calleja 1998, pp. 481–2; the claimant accused Olazábal of asking for trouble when interfering in French religious issues, Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 449

- under the threat of expulsion, La Epoca 07.10.10, available here

- González Calleja 1998, p. 481

- La Correspondencia de España 16.05.11, available here

- In July 1912 the press reported him was from France, see La Correspondencia de España 06.07.12, available here; the French authorities were suspecting him of conspiring against the Portuguese government; Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 449

- In April 1883 the press reported that Olazábal, accompanying the Counts of Caserta and Bardi, attended the hunting parties held in Hungary by Emperor Franz Joseph, see Diario de San Sebastián 05.04.1883, available here

- ABC 01.04.11915, available here

Further reading

- Françoise Vigier, Les métamorphoses du Grand Casino de Saint-Jean-de-Luz (1881-1958), in Ekaina, n°121 (1er trimestre 2012), pp. 33–58

- Agustín Fernández Escudero, El marqués de Cerralbo (1845–1922): biografía politica [PhD thesis], Madrid 2012