Vector-radix FFT algorithm

The vector-radix FFT algorithm, is a multidimensional fast Fourier transform (FFT) algorithm, which is a generalization of the ordinary Cooley–Tukey FFT algorithm that divides the transform dimensions by arbitrary radices. It breaks a multidimensional (MD) discrete Fourier transform (DFT) down into successively smaller MD DFTs until, ultimately, only trivial MD DFTs need to be evaluated.[1]

The most common multidimensional FFT algorithm is the row-column algorithm, which means transforming the array first in one index and then in the other, see more in FFT. Then a radix-2 direct 2-D FFT has been developed,[2] and it can eliminate 25% of the multiplies as compared to the conventional row-column approach. And this algorithm has been extended to rectangular arrays and arbitrary radices,[3] which is the general vector-radix algorithm.

Vector-radix FFT algorithm can reduce the number of complex multiplications significantly, compared to row-vector algorithm. For example, for a element matrix (M dimensions, and size N on each dimension), the number of complex multiples of vector-radix FFT algorithm for radix-2 is , meanwhile, for row-column algorithm, it is . And generally, even larger savings in multiplies are obtained when this algorithm is operated on larger radices and on higher dimensional arrays.[3]

Overall, the vector-radix algorithm significantly reduces the structural complexity of the traditional DFT having a better indexing scheme, at the expense of a slight increase in arithmetic operations. So this algorithm is widely used for many applications in engineering, science, and mathematics, for example, implementations in image processing,[4] and high speed FFT processor designing.[5]

2-D DIT case

As with Cooley–Tukey FFT algorithm, two dimensional vector-radix FFT is derived by decomposing the regular 2-D DFT into sums of smaller DFT's multiplied by "twiddle" factor.

A decimation-in-time (DIT) algorithm means the decomposition is based on time domain , see more in Cooley–Tukey FFT algorithm.

We suppose the 2-D DFT

where ,and , and is a matrix, and .

For simplicity, let us assume that , and radix-( are integers).

Using the change of variables:

- , where

- , where

where or , then the two dimensional DFT can be written as:[6]

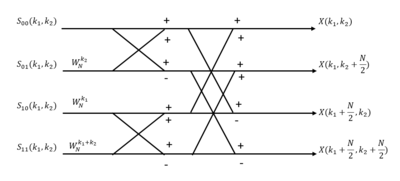

The equation above defines the basic structure of the 2-D DIT radix- "butterfly". (See 1-D "butterfly" in Cooley–Tukey FFT algorithm)

When , the equation can be broken into four summations: one over those samples of x for which both and are even, one for which is even and is odd, one of which is odd and is even, and one for which both and are odd,[1] and this leads to:

where

2-D DIF case

Similarly, a decimation-in-frequency (DIF, also called the Sande–Tukey algorithm) algorithm means the decomposition is based on frequency domain , see more in Cooley–Tukey FFT algorithm.

Using the change of variables:

- , where

- , where

where or , and the DFT equation can be written as:[6]

Other approaches

The split-radix FFT algorithm has been proved to be a useful method for 1-D DFT. And this method has been applied to the vector-radix FFT to obtain a split vector-radix FFT.[6][7]

In conventional 2-D vector-radix algorithm, we decompose the indices into 4 groups:

By the split vector-radix algorithm, the first three groups remain unchanged, the fourth odd-odd group is further decomposed into another four sub-groups, and seven groups in total:

That means the fourth term in 2-D DIT radix- equation, becomes:[8]

where

The 2-D N by N DFT is then obtained by successive use of the above decomposition, up to the last stage.

It has been shown that the split vector radix algorithm has saved about 30% of the complex multiplications and about the same number of the complex additions for typical array, compared with the vector-radix algorithm.[7]

References

- Dudgeon, Dan; Russell, Mersereau (September 1983). Multidimensional Digital Signal Processing. Prentice Hall. p. 76. ISBN 0136049591.

- Rivard, G. (1977). "Direct fast Fourier transform of bivariate functions". IEEE Transactions on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing. 25 (3): 250–252. doi:10.1109/TASSP.1977.1162951.

- Harris, D.; McClellan, J.; Chan, D.; Schuessler, H. (1977). "Vector radix fast Fourier transform". IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, ICASSP '77. 2: 548–551. doi:10.1109/ICASSP.1977.1170349.

- Buijs, H.; Pomerleau, A.; Fournier, M.; Tam, W. (Dec 1974). "Implementation of a fast Fourier transform (FFT) for image processing applications". IEEE Transactions on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing. 22 (6): 420–424. doi:10.1109/TASSP.1974.1162620.

- Badar, S.; Dandekar, D. (2015). "High speed FFT processor design using radix −4 pipelined architecture". 2015 International Conference on Industrial Instrumentation and Control (ICIC), Pune, 2015: 1050–1055. doi:10.1109/IIC.2015.7150901. ISBN 978-1-4799-7165-7.

- Chan, S. C.; Ho, K. L. (1992). "Split vector-radix fast Fourier transform". IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing. 40 (8): 2029–2039. Bibcode:1992ITSP...40.2029C. doi:10.1109/78.150004.

- Pei, Soo-Chang; Wu, Ja-Lin (April 1987). "Split vector radix 2D fast Fourier transform". IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, ICASSP '87. 12: 1987–1990. doi:10.1109/ICASSP.1987.1169345.

- Wu, H.; Paoloni, F. (Aug 1989). "On the two-dimensional vector split-radix FFT algorithm". IEEE Transactions on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing. 37 (8): 1302–1304. doi:10.1109/29.31283.