Vani archaeological site

The Vani archaeological site (Georgian: ვანის ნაქალაქარი, translit.: vanis nakalakari, literally, "the ruined/former town of Vani") is a multi-layer archaeological site in western Georgia, located on a hill at the town of Vani in the Imereti region. It is the best studied site in the hinterland of an ancient region, known to the Classical world as Colchis, and has been inscribed on the list of the Immovable Cultural Monuments of National Significance.[1]

| Vani archaeological site | |

|---|---|

| Native name Georgian: ვანის ნაქალაქარი | |

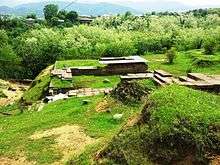

Vani. Ruins of an ancient settlement. | |

| Location | Vani, Vani Municipality Imereti, Georgia |

| Coordinates | 42.085050°N 42.504008°E |

Invalid designation | |

| Type | Archaeological |

| Designated | 2007 |

Location of Vani archaeological site in Georgia | |

Remains of fortifications and temples, locally produced and imported Greek pottery, and sophisticated local goldwork—now on display at the Vani Archaeoogical Museum and the Museum of Georgia in Tbilisi—indicate that Vani was a vibrant urban settlement from the 8th century down to the mid-1st century BC. An ancient name for Vani is unknown: two competing hypotheses identify the site with the Surium of Pliny the Elder or the Leucothea of Strabo.

Location

The Vani site is situated at the western outskirts of the modern town, on Akhvlediani Gora, a low terraced triangular hill of approximately 8.5 ha, flanked on two sides by deep ravines.[2] The foothills around Vani form the point of the nearly triangular wetland region of Colchis, the base of which is along the eastern Black Sea coast, dotted by Greek colonies in antiquity.[3] The site itself was located on the intersection of ancient trade routes, enjoying a commanding position over the adjoining plain.[2]

Archaeological study

Occasional archaeological finds at Vani were first reported by the French scholar Marie-Félicité Brosset in 1851, followed by a series of notes in the Georgian press in the 1870s. Preliminary archaeological survey was headed by Alexander Stoyanov in 1889, and on a larger scale, by Ekvtime Taqaishvili in 1896 and from 1901 to 1903. Further reconnaissance was conducted in 1936, followed by more systematic, but irregular digs under Nino Khoshtaria from 1947 to 1962. In 1966, the excavations resumed on a regular basis as part of the Center for Archaeology expedition, directed by Otar Lordkipanidze and, after his death in 2002, by Darejan Kacharava.[4]

Features

Vani is the most substantially excavated site in the Colchian hinterland and offers the best evidence of the development of this area throughout the period of Greek colonization of the coastline into the Roman period. Four phases have been identified at the Vani site from the 8th century down to the mid-1st century BC.[5]

First and second phases

The most archaic Vani appears to have been a small settlement, containing the log-cabins, also known elsewhere in Colchis.[5] Layers dated to the first phase (c. 800–600 BC) have yielded fragments of baked daub with wicker imprints, pottery—wheel-made, well-baked, black-fired, and polished on the surface—and terracotta figurines of various animals.[6] At that time, Lordkipanidze believes, Vani was an emerging cult center and wielded significant influence over surrounding settlements.[7]

In the second phase (c. 600–350 BC) there was a tangible increase in wealth at Vani, as evidence by large locally produced earthenware storage-jars, rich burials with grave good such as fine gold work of local production—with affinities to both the Greek and Middle Eastern cultures—and the appearance of imported Greek pottery, the earliest being a Chiot chalice from the early 6th century.[8] Vani appears to have been a seat of the local elite which dominated a stratified social hierarchy.[9][10]

Third phase

During the third phase at Vani (c. 350–250 BC),[11] Changes in the material culture are prominent. The principal sanctuary on the hilltop had been destroyed and burnt and the ritual ditches had ceased to function; new stone buildings appear including a circuit wall. In addition, traditional Colchis pottery gives way to new forms, notably pear-shaped jugs with red paint on a light ground, familiar in eastern Georgia, anciently known as Iberia, and Greek influence becomes more prominent on the goldwork. Burial in storage-jars becomes the predominant mode.[12] An important find is a 4th-century BC signet-ring bearing, in Greek letters, the name of "Dedatos",[13] probably a local ruler.[14] Lordkipanidze assumes some of these changes may reflect the infiltration of tribes from Iberia, which at that time experienced urbanization, state formation, and expansion.[15][13]

Fourth phase

The fourth phase at Vani runs from c. 250 BC to c. 47 BC.[14] This was the period of relative decline in central Colchis: many settlements disappeared as did rich burials. The Vani site saw the erection of a strong circuit wall, with towers and a heavily defended gate,[16] built of mudbrick on a stone socle.[14] Around 150 BC, much of the city was destroyed as evidenced by dating the stamped Rhodian amphorae unearthed at Vani. By the end of the 2nd century BC, there was renewed building activity: parts of the ruins were methodically levelled and new buildings were constructed. The northern part of the hill was dominated by the gate and defensive structures and the lower terrace housed a large temple complex.[17] The large buildings of the city were decorated with Corinthian capitals and lion-head waterspouts. Hellenistic statues in bronze attest to the impact of Greek culture.[18] According to Lordkipanidze, Vani became a city-sanctuary similar to the temple communities of ancient Anatolia;[14] David Braund argues there is the lack of evidence and identification of the function of many buildings at Vani is problematic.[19]

Destruction

In the middle of the 1st century BC, the ancient city at Vani was attacked and destroyed. The gate, sanctuary with its mosaic floor, the stepped altar, and the round temple on the central terrace of the hill exhibit signs of violence and conflagration: walls razed to the foundation, fired stones, baked tiles and mudbrick, and charred beams.[20] It is unknown who was responsible for the destruction of the city: Pompey, who led the first Roman incursion into the Caucasian hinterland in 65 BC, Pharnaces II, who tried to conquer Colchis and Pontus in 49 BC, and Mithridates of Pergamon, who was made by Julius Caesar successor to Pharnaces in 47 BC, are all possible candidates.[18] According to Lordkipanidze, two destruction layers can be observed within a few years of each other: one attributed to an invasion by Pharnaces and the other to that by Mithridates.[21]

Vani never recovered to its past level. Remains from the Roman and medieval periods are very fragmentary, such as a c. 200 AD robbed burial in a bronze sarcophagus, and the medieval ruins of a church, a hilltop kiln, and a warrior's burial.[20]

Ancient name

The name of the city unearthed at Vani is unknown. Two competing hypotheses have been put forward. One, proposed by Nino Khoshtaria, identifies Vani with a Colchian city named Surium by the 1st-century AD Roman author Pliny the Elder. Surium is also mentioned by Ptolemy. A settlement named Surtum is located by the Ravenna Cosmography in the heartland of Colchis, somewhere between Rhodopolis and Sarapanis, the location roughly corresponding to that of Vani. The toponym Souris also occurs on a bronze inscription from Vani.[22]

An alternative hypothesis, suggested by Otar Lordkipanidze, has it that Vani is the site of the temple of Leucothea in Colchis reported by Strabo as being sacked by Pharnaces II of Pontus and then by Mithridates of Pergamum. Opponents point to the fact that, according to Strabo, the temple was close to the common border of Colchis, Iberia, and Armenia; the location does not suit Vani.[23]

Citations

- "List of Immovable Cultural Monuments" (PDF) (in Georgian). National Agency for Cultural Heritage Preservation of Georgia. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- Lordkipanidze 1991, p. 155.

- Braund 1994, p. 123.

- "The former city-site of Vani" [Vani site]. Georgian National Museum. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- Braund 1994, p. 127.

- Lordkipanidze 1991, pp. 156–157.

- Lordkipanidze 1991, pp. 159–160.

- Lordkipanidze 1991, pp. 161–166.

- Braund 1994, pp. 128–129.

- Lordkipanidze 1991, pp. 173–174.

- Lordkipanidze 1991, p. 177.

- Braund 1994, pp. 135–136.

- Braund 1994, p. 136.

- Lordkipanidze 1991, p. 184.

- Lordkipanidze 1991, p. 183.

- Braund 1994, p. 144.

- Lordkipanidze 1991, pp. 186–187.

- Braund 1994, p. 147.

- Braund 1994, p. 146.

- Lordkipanidze 1991, p. 195.

- Lordkipanidze 1991, p. 194.

- Braund 1994, p. 148.

- Braund 1994, pp. 148–149.

Sources

- Braund, David (1994). Georgia in antiquity: a history of Colchis and Transcaucasian Iberia, 550 BC–AD 562. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198144731.

- Lordkipanidze, Otar (1991). "Vani: An Ancient City of Colchis". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. 32 (1): 151–195.