Valentina Kulagina

Valentina Kulagina, full name Valentina Nikiforovna Kulagina-Klutsis (Russian: Валентина Никифоровна Кулагина-Клуцис, 1902–1987[1]) was a Russian painter and book, poster, and exhibition designer. She was a central figure in Constructivist avant-garde in the early 20th century alongside El Lissitzky, Alexander Rodchenko other and her husband Gustav Klutsis. She is known for the Soviet revolutionary and Stalinist propaganda she produced in collaboration with Klutsis.

Valentina Kulagina | |

|---|---|

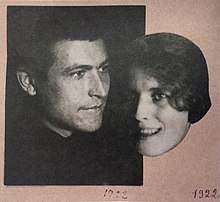

Kulagina, a 1929 photo by Gustav Klutsis | |

| Born | 1902 Moscow, Russia |

| Died | 14 December 1987 (aged 85) Moscow, Russia |

| Alma mater | Vkhutemas |

| Spouse(s) | Gustav Klutsis |

Biography

Kulagina left State Free Art Studios and entered the state-run art school Vkhutemas in 1920 at the urging of teacher Gustav Klutsis, whom she had recently met. On 2 February 1921, the couple wed and lived together at the school's headquarters.[2] In 1928, Kulagina joined the artists' group October, of which her husband was already a member. In 1930 she designed a poster for International Working Women's Day, employing avant-garde techniques combined with typography, lithography, and photomontage. Starting in 1932 Kulagina saw her works frequently rejected by the Communist Party's Central Committee.[3]

Her work as a designer began before she graduated the school, with the Soviet Pavilion at the Pressa exhibition in Cologne including areas which she designed. Later, she worked for IZOGIZ (the State Art Publishing Agency) and VOKS (the All-Union Society of Cultural Relations with Abroad) and VSKhV (The All-Union Agricultural Exhibition).

Klutsis' and Kulagina's work was complementary, and their style of photomontage combined with graphic work saw them implemented as official revolutionary poster producers for the Communist Party under Stalin. On 17 January 1938, Klutsis was arrested as he prepared to leave for the New York World's Fair. Kulagina was never told the truth as to what happened to her husband, believing for the remainder of her life that he had died of a heart attack while imprisoned.[2] In 1989, two years after her death in Moscow, it was discovered that he had been executed by order of Stalin, very soon after his arrest.

Work

Within the early formation of Soviet Union, politics was a potent influence on the artistic community, and the art and design produced during this early period is known for its revolutionary zeal and joyous utopianism. With this subject matter, Kulagina's work combined drawing and graphic symbolism with photomontage techniques (that had been pioneered by her husband). It was a combination that distinctively separated her work from Klutsis'. Klutsis and Kulagina never worked on projects together, their work was collaborative nevertheless, and was strengthened by one being around the other.

Though Klutsis and Kulagina are known for these official pieces for the government, they also ran a personal art and photography practice, utilising styles such as superimposition and photomontage, often portraits of each other.

As the political environment in Russia began to dissolve in the 1930s, Klutsis and Kulagina came under increasing pressure to limit the subject matter and humour that they had employed for official posters and graphic work, and their posters came to represent Stalinist visual rhetoric and propaganda rather than its original revolutionary hope.

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Valentina Kulagina. |

- "Valentina Kulagina – 2 Artworks, Bio & Shows on Artsy". www.artsy.net. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Gustav Klutsis and Valentina Kulagina: Photography and Montage After Constructivism. museum.icp.org (2004)

- Poggi, Christine (2006). "Mass, Pack, and Mob: Art in the Age of the Crowd". Crowds. Stanford (California): Stanford University Press. pp. 178–180. ISBN 0-8047-5480-2.