Utopia, Northern Territory

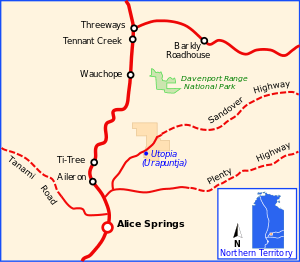

Utopia is an Aboriginal Australian homeland formed in November 1978 by the amalgamation of the former Utopia pastoral lease with a tract of unalienable land to its north. It covers an area of 3,500 km2 (1,400 sq mi), transected by the Sandover River, and lies on a traditional boundary of the Alyawarra and Anmatjirra people, the two language groups which predominate there today. The name is probably a corruption of Uturupa, which means "big sandhill", a region in the north-west extremity of the area.

It has a number of unique elements. It is one of a minority of communities created by autonomous activism in the early phase of the land rights movement. It was neither a former mission, nor a government settlement (Aboriginal reserve), but was successfully claimed by Aboriginal Australians who had never been fully dispossessed. Its people have expressly repudiated any municipal establishment, and instead live in a score of outstations or clan sites, each with a traditional claim to the place.

History

European occupation of the Sandover region began in the early 1880s in the southern Davenport Ranges, then on the Elkedra and the Bundey rivers. These outfits did not have good resources and were short of surface water; most were abandoned by 1895 because of drought and conflict with the Aboriginal inhabitants.

A second phase began in the decade from 1915 to 1925. The two portions which later became Utopia station were first leased by cattlemen in 1928. Relations between the Aboriginal people and cattlemen appear to have been problematic north of Utopia in Alyawarra/Anmatjirra/Kaititja country, but more cooperative in the south: Utopia, MacDonald Downs, Mt Swan, and Bundey River. The Chalmers family sold the lease of Utopia as a going concern to the Aboriginal Land Fund in 1976. The cattle enterprise had largely lapsed by the time the two land claims were settled in 1978 and 1980.

Alyawarra people displaced by the violence during European dispossession fled in significant numbers across Wakaya country to Soudan and Lake Nash on the Barkly Tableland, and to refuges in the east in Kaytete lands and beyond. That is why Utopia people today have close kinship ties with the communities of Ali Carung, Ti-Tree, Harts Range and Lake Nash. This movement of people has been called the Outstation movement.

In 2013, Utopia lent its name to, and was a major focus of, a documentary film by John Pilger named Utopia, highlighting historical and current issues faced by Indigenous communities across Australia.[1]

Population

The population at Utopia is a changing quantity, but was roughly 1,200 people in 2011.[2] A typical outstation complement, of which there are 16 communities, is 20–100.

Services and facilities

A community-owned store together with the council offices makes up a sort of municipal centre at the largest outstation, Arlparra. Five small schools are distributed among the outstations, and a bus provides transportation to children who do not live at one of these.

A medical clinic occupies its own site; it is staffed by a doctor, several nurses and a group of local health workers. The clinic delivers most of its services at the outstations by way of a schedule of weekly visits. Funding of essential services is provided by direct Commonwealth grants to the Aboriginal Corporation via the Community Council and the Health Council; both representative bodies are elected by due process annually. The Northern Territory Government provides the educational infrastructure and budgets.

Traditional lifestyle

The people harvest and consume traditional foods – and to some extent medicines – especially the elders. This practice is likely to have mitigated the prevalence of metabolic diseases seen in other populations, which have been very damaging to Aboriginal health.

Health

A series of population health surveys carried out between 1986 and 2004 showed that Utopia people were significantly healthier than comparable groups, particularly their rates of mortality. This has been attributed to the more active "outstation way of life". Community living, cultural factors and the primary health care facility were also important factors.[3][4] This finding is of considerable interest to students of indigenous health. Study of the basis of this difference continues.

In 2014, the borehole supplying water to the community of Utopia was broken during maintenance by Barkly Regional Council, and delivery of water via truck was irregular and insufficient, leading to the spread of disease.[5][6] While there was dispute by authorities about the extent of the water shortage[7][8][9] the Northern Territory government eventually agreed to fund the bore repairs, and money raised by a crowdfunding campaign was transferred to the Urapuntja Health Service.[10]

Prohibition

Alcohol is not permitted anywhere at Utopia, but although the ban is fairly regularly broken, the effects of abuse are intermittent. The problem is minor here compared with many other communities. There is almost no abuse of other intoxicants.

Art

Utopia's Aboriginal artists have been remarkably successful, and continue to produce distinctive works that are collected by people in Australia and all over the world.[11] Notable artists from Utopia include Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Gloria Petyarre, Kathleen Petyarre and Jeanna Petyarre.

Health and well-being

The most recent 30-year history of Utopia is a record of self-determination against a background of well-developed communal will and widespread participation. The era of settlement included some profitable relations with white pastoralists and some degree of continuous Indigenous occupation. The community has had some success in mitigating the clinical disorders associated with transition to sedentary life, and minimising the advent of destructive behaviours and intoxicants. In addition, they have maintained a strong commitment to traditional practices and customs, which support identity in the face of coercive change. Sanitation issues such as the lack of rubbish collection and poor hygiene are significant obstacles to greater well-being.[2]

Notable residents

- Aboriginal artists including Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Barbara Weir, Minnie Pwerle, Kathleen Petyarre, Gloria Petyarre and Janelle Stockman.

- Rosalie Kunoth-Monks, Chancellor of Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education. She played the title role at age 14 in the 1955 Charles Chauvel film, Jedda.

References

- Pilger, John. "Utopia". John Pilger.com. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- Lisa Martin (31 October 2011). "Utopia a land short of toilets, not hope". ninemsm.com. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- Rowley, K. (2008). "Morbidity and Mortality for an Australian Aboriginal Population: 10 year follow up in a decentralised community". Medical Journal of Australia. 188 (5): 283–7.

- "The Link Between Primary Health Care and Health Outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians". Department of Health and Ageing. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- Petrova, Sasha (28 August 2014). ""Water shortage in Utopia Homelands spreads scabies"". NT News. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- Liddle, Celeste (15 September 2014). ""Ten weeks dry: water is still a privilege, not a right, in Indigenous Australia"". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ""Crisis? What Crisis? Utopia To Get New Bore, But Water Shortage Never Happened"". New Matilda. 29 September 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ""Urapuntja Clinic Bore"" (PDF) (Press release). NT government. Barkly Regional Council. 29 August 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ""Urapuntja Clinic Bore Update"" (PDF) (Press release). NT government. Barkly Regional Council. 26 September 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- Stewart, Anthony (22 October 2014). ""Health service to get Utopia water donations"". Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- "Utopian Aboriginal Art". Utopian Aboriginal Art. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

Further reading

- Gooch, Rodney in association with Anne Marie Brody; portrait photographs by Adler, Nicholas; the Utopia artists (1990). Utopia : a picture story : 88 silk batiks from the Robert Holmes à Court Collection. Perth: Heytesbury Holdings. ISBN 0646009095. Contains a collection of batik designs together with the story of their creation and exhibition.

- Green, Jennifer Anne; Institute for Aboriginal Development (Alice Springs, N.T.) (1992), Alyawarr to English dictionary, Institute for Aboriginal Development, ISBN 978-0-949659-66-8

- Kngwarreye, Emily Kame; Benjamin, Roger; Neale, Margo (1998), Emily Kame Kngwarreye: Alhalkere: paintings from Utopia, Queensland Art Gallery, ISBN 978-0-646-34829-2

- Nicholls, essays by Christine; North, Ian (2001). Kathleen Petyarre : Genius of Place. Kent Town, S. Aust.: Wakefield Press. ISBN 1862545464.

- Toohey, John Leslie, 1930– (1980), Anmatjirra and Alyawarra land claim to Utopia pastoral lease: report, The Office of the Aboriginal Land Commissioner, retrieved 31 May 2015CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Vanovac, Neda (26 June 2017). "Barker College agrees to launch Aboriginal academy for girls in Utopia homelands". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation.