Useware

Useware is a generic term introduced in 1998 that denotes all hard- and software components of a technical system which serve its interactive use. The main idea of the term Useware is the focus of technical design according to human abilities and needs. The only promising method (Zuehlke, 2007) to design future technical products and systems is to understand human abilities and limitations and to focus the technology on these abilities and limitations.

Today Useware requires its own need for development which is partly higher than in the classical development fields (Zuehlke, 2004). Thus usability is increasingly recognized as a value-adding factor. Often the Useware of machines with similar or equal technical functions is the only characteristic that sets it apart (Zuehlke, 2002).

Useware-Engineering

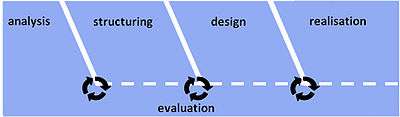

Similar to Software Engineering Useware Engineering implies the standardized production of Useware by engineers and the associated processes (see figure 1). The aim of Useware engineering is to develop interfaces which are easy to understand and efficient to use. These interfaces are adapted to the human work task. Also the interfaces represent machine functionality without overemphasizing it.

Thus the objective of systematic Useware Engineering guarantees high usability based on the actual tasks of the users. However, it requires an approach which comprises active and iterative participation of different groups of people.

Therefore, the professional associations GfA (Gesellschaft für Arbeitswissenschaft), GI (Gesellschaft für Informatik), VDE-ITG (The Information Technology Society in VDE) and VDI/VDE GMA (The Society for Measurement and Automatic Control in the VDI/VDE) agreed in 1998 on defining Useware as a new term. The term Useware was intentionally selected in linguistic analogy to hard- and software.

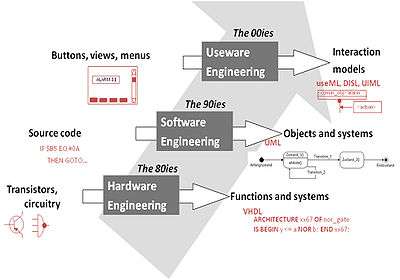

Consequently, Useware Engineering developed in a similar way to the development of engineering processes (see figure 2). This reinforces the principal demand for structured development of user-centered user interfaces expressed e.g. by Ben Shneiderman (Shneiderman, 1998). After many years of function-oriented development human abilities and needs are brought into focus. The only promising method to develop future technical products and systems is to understand the users’ abilities and limitations and to aim the technology in that direction (Zuehlke, 2007).

The Useware development process (see figure 1) distinguishes the following steps: analysis, structure design, design, realisation and evaluation. Each of these steps should not be regarded separately but rather overlapping. The continuity of the process as well as the use of suitable tools, e.g. on the basis of the Extensible Markup Language (XML) make it possible to avoid information losses and media breaks.

Analysis

Humans learn, think and work in completely different ways. Therefore the first step in the development of a user interface is to analyze the users, their tasks and their work environment in order to identify the requirements and needs of these users. This step forms the basis for a user- and task-oriented user interface. Both humans and machines are considered as interaction partners. The analysis of the users and their behavior employs different methods like e.g. structured interviews, observations, card sorting etc. They should give a preferably complete image of the working task, the various groups of users and their working environment. To use these methods several professional experts, e.g. engineers, computer scientists and psychologists should be involved. Especially in the analysis phase, task models are generated for documentation and user interface generation, which implicitly contains a function model of the process and/or of the machine (Meixner and Goerlich, 2008).

Structure design

The results of the analysis phase are adjusted within the structuring phase. An abstract use model (Zuehlke and Thiels, 2008) is developed on the basis of this information which is platform independent. The result of the structuring phase is the basic structure of the future user interface. The use model is a formal model of use contexts, tasks and information demanding the functionality of the machine. The use model is modeled using the Useware Markup Language, useML (Reuther, 2003) within a model based development environment.

Design

Parallel to the structuring phase a hardware-platform for the Useware has to be selected. This selection is based on environmental requirements of the machine usage (pollution, noise, vibration, ...) on the one hand and the user’s requirements (display size, optimal interaction device, …) on the other. Furthermore economic factors have to be considered. If the model is intensively networked or is composed of a huge number of elements, sufficient display size for visualizing information structure should be provided. These factors partly depend on user groups and contexts of use (Goerlich et al., 2008).

Realisation/Prototyping

During the prototyping developers must select a development tool. If the selected development environment provides import possibilities, the developed use model can be imported and the derivation of the user interface can be processed. In most cases the processing affects the realisation of dynamic components as well as the fine design of dialogues. Often there is a media break between the structuring and the (fine) design phase. Today‘s field of development tools have a wide variety of notations. Developers need to represent the Useware in form of prototypes, e.g. paper prototypes or Microsoft PowerPoint prototypes.

Evaluation

A continuous evaluation during the development process allows an early detection of product problems and thus reduces development costs (Bias and Mayhew, 1994). It is relevant to include structural aspects e.g. navigational concepts etc. in the evaluation and not only design aspects. Some tests have shown that 60% of all use errors are not the result of bad design but due to structural deficiencies. The evaluation phase needs to be considered as a cross-sectional task in the entire development process. Thus it is very important to integrate users in the development of the product.

References

- Bias, R. G.; Mayhew, D. J. (1994). Cost-justifying usability. Boston, MA: Academic Press

- Goerlich, D.; Thiels, N.; Meixner, G. (2007): Personalized Use Models in Ambient Intelligence Environments. Proc. of the 17th IFAC World Congress, Seoul, Korea, 2008

- Meixner, G.; Goerlich, D. (2008): Aufgabenmodellierung als Kernelement eines nutzerzentrierten Entwicklungsprozesses für Bedienoberflächen. Workshop "Verhaltensmodellierung: Best Practices und neue Erkenntnisse", Fachtagung Modellierung, Berlin, Germany, März 2008

- Reuther, A. (2003): useML–Systematische Entwicklung von Maschinenbediensystemen mit XML. Fortschritt-Berichte pak, Band 8. Kaiserslautern: Technische Universität Kaiserslautern

- Shneiderman, B. (1998): Designing the user interface: Strategies for Effective Human-Computer-Interaction. Massachusetts/USA: Addison-Wesley

- Zuehlke, D. (2002): Useware–Herausforderung der Zukunft. Automatisierungstechnische Praxis (atp), 9/2002, S.73-78

- Zuehlke, D. (2004): Useware-Engineering für technische Systeme. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag

- Zuehlke, D. (2007): Useware. In: K. Landau (Hrsg.): Lexikon Arbeitsgestaltung. Best Practice im Arbeitsprozess. Stuttgart: Gentner Verlag; ergonomia Verlag

- Zuehlke, D.; Thiels, N. (2008): Useware engineering: a methodology for the development of user-friendly interfaces. Library Hi Tech, 26(1):126-140

Further literature

- Oberquelle, H. (2002): Useware Design and Evolution: Bridging Social Thinking and Software Construction. In: Y. Dittrich, C. Floyd, R. Klischewski (Hrsg.): Social Thinking–Software Practice, S. 391-408, Cambridge, London: MIT-Press

- For further informationen see the Useware-Forum 17 March 2009