Typhoon Gay (1992)

Typhoon Gay, known in the Philippines as Typhoon Seniang, was the strongest and longest-lasting storm of the 1992 Pacific typhoon season. It formed on November 14 near the International Date Line from a monsoon trough, which also spawned two other systems. Typhoon Gay later moved through the Marshall Islands as an intensifying typhoon, and after passing through the country it reached its peak intensity over open waters. The Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) estimated peak winds of 295 km/h (185 mph) and a minimum barometric pressure of 872 mb (25.8 inHg). However, the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), which is the official warning center in the western Pacific, estimated winds of 205 km/h (125 mph), with a pressure of 900 mbar (27 inHg). Gay weakened rapidly after peaking because of interaction with another typhoon, and it struck Guam with winds of 160 km/h (100 mph) on November 23. The typhoon briefly re-intensified before weakening and becoming extratropical south of Japan on November 30.

| Typhoon (JMA scale) | |

|---|---|

| Category 5 super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

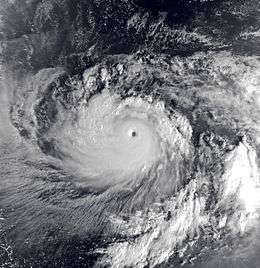

Typhoon Gay near peak intensity on November 20 | |

| Formed | November 14, 1992 |

| Dissipated | December 1, 1992 |

| (Extratropical after November 29) | |

| Highest winds | 10-minute sustained: 205 km/h (125 mph) 1-minute sustained: 295 km/h (185 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 900 hPa (mbar); 26.58 inHg |

| Fatalities | 1 direct |

| Areas affected | Marshall Islands, Caroline Islands, Mariana Islands, Guam, Japan, Aleutian Islands |

| Part of the 1992 Pacific typhoon season | |

The typhoon first affected the Marshall Islands, where 5,000 people became homeless and heavy crop damage was reported. The nation's capital of Majuro experienced power and water outages during the storm. There were no fatalities among Marshall Islands citizens, although the typhoon killed a sailor traveling around the world. When Gay struck Guam, it became the sixth typhoon of the year to affect the island. Most of the weaker structures had been destroyed during Typhoon Omar earlier in the year, resulting in little additional damage from Gay. Because of its substantial weakening, the typhoon had a disrupted inner-core and produced minimal rainfall. However, strong winds scorched the plants on Guam with saltwater, causing extensive defoliation. Further north, high waves from the typhoon destroyed a house on Saipan, and heavy rainfall in Okinawa, Japan, caused flooding and power outages.

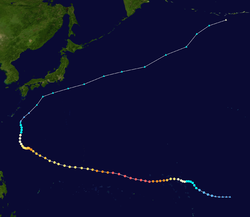

Meteorological history

The origins of Typhoon Gay were from a tropical disturbance east of the International Date Line along a monsoon trough that extended west to the South China Sea in mid-November 1992. The same trough had earlier spawned Tropical Storm Forrest and would later create Typhoon Hunt. The tropical disturbance moved westward across the dateline and gradually became better organized with increased convection. On November 14, the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC)[nb 1] issued a Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert. At 1800 UTC that day, the agency initiated advisories on Tropical Depression 31W, located to the east of the Marshall Islands.[2] The Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA)[nb 2] also assessed that the depression had developed by that time.[4] The next day, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Gay.[2][4]

For most of Typhoon Gay's existence, a strong anticyclone to its north steered the storm to the west or west-northwest. The JTWC upgraded the storm to typhoon status early on November 17, and the JMA followed suit the next day. Gay first affected Mejit Island and eventually crossed the central portion of the Marshall Islands. Owing to favorable sea surface temperatures and upper-level wind patterns, the storm entered a phase of rapid deepening similar to other November typhoons near that location.[2] On November 19, the JTWC upgraded Gay to a super typhoon, which is a typhoon with 1-minute sustained winds of 240 km/h (150 mph). Gradual intensification ensued, and based on satellite estimates, the JTWC estimated that Typhoon Gay attained peak winds of 295 km/h (185 mph) at 0000 UTC on November 21.[5] The agency also estimated that the typhoon reached a minimum barometric pressure of 872 mb (25.8 inHg), which would have made Gay the most intense typhoon since Typhoon Tip in 1979, tying with Hurricane Patricia in 2015 for the second-strongest tropical cyclone worldwide.[2] At the same time, the JMA estimated peak 10-minute sustained winds of 205 km/h (125 mph), with a pressure of 900 mbar (27 inHg).[4]

After Gay attained its peak intensity, outflow from Typhoon Hunt to its northwest increased the wind shear over the typhoon. The wind shear deteriorated Gay's northern eyewall, causing the typhoon to weaken. In the 24 hours after Gay reached its peak intensity, the JTWC estimated that the winds had decreased by 65 km/h (40 mph) to below super typhoon status; such rapid weakening is uncommon for a storm over open waters. Tropical cyclone forecast models had anticipated Gay to make a turn to the north and northeast, but it maintained a west-northwest track toward Guam. Despite weakening steadily, the typhoon maintained a large size with a wind diameter of 1,480 km (920 mi). Around 0000 UTC on November 23, Gay made landfall on Guam, becoming the third typhoon in three months to strike the island—the others were Typhoon Omar in August and Typhoon Brian in October.[2] Both the JTWC and the JMA estimated the typhoon to have had winds of 160 km/h (100 mph) at landfall.[2] The influence from Typhoon Hunt diminished after Gay affected Guam, allowing it to begin restrengthening. Late on November 25, the JTWC estimated that the typhoon attained a secondary peak intensity of 215 km/h (135 mph). Gay subsequently slowed while moving along the western periphery of the subtropical ridge, and it turned north while gradually weakening.[2] On November 28, the JMA downgraded Gay to a tropical storm,[4] and the JTWC followed suit the next day.[5] The JMA assessed that Gay became an extratropical cyclone at 0000 UTC on November 30;[4] however, the JTWC continued issuing advisories until December 1, making it the longest-lasting typhoon of the season with 63 advisories.[2] The remnant of Gay accelerated and turned to the northeast, passing to the southeast of Japan and crossing the International Date Line.[4]

Preparations and impact

Marshall Islands

Typhoon Gay first affected the Marshall Islands, striking several atolls in the archipelago with typhoon-force winds. On Mejit Island, the first island to be affected, the typhoon destroyed every wooden structure and left most of the islanders homeless. High winds downed all of the island's trees and destroyed 75% of the crops. Nearby, Ailuk Atoll experienced similar winds, though house damage was minor despite similar crop losses. The large wind field extended to the south, affecting Maloelap and Aur atolls with winds that damaged 30% of the houses and crops. Further south, the Marshall Islands capital city of Majuro experienced lightning strikes from the typhoon, which caused an island-wide power outage and cuts to the water supply and radio communication. Debris from the storm closed the Marshall Islands International Airport for two days. On Ujae Atoll, the typhoon destroyed an automated meteorological observing station that had been installed in 1989. The typhoon left over 5,000 people homeless across the country, but there were no native deaths and only one injury in the archipelago owing to well-executed warnings and preparations.[2] However, large waves from the typhoon sank a boat in a small lagoon, killing one of the boat's two sailors.[6][7]

Guam and Northern Marianas

After affecting the Marshall Islands, Gay tracked toward Guam and became the fifth typhoon to come within 110 km (68 mi) of the island in six months. Extensive preparations were made, including the sending of ships to mitigate damage[2] and flying United States Air Force planes to other bases in the region.[8] The schools, government buildings, airport, and port were closed, and about 4,300 people evacuated to storm shelters. Further north, 1,639 people evacuated to storm shelters on Saipan, which set the record for the most storm evacuees at the time.[2]

Despite weakening greatly from its peak intensity, Gay struck Guam with sustained winds of 160 km/h (100 mph), with gusts to 195 km/h (120 mph) on Nimitz Hill.[2] The winds were strong enough to disrupt power and water utilities, as well as destroy a few houses.[9] As a result of its weakening, Gay had a disrupted inner-core with little precipitation, which prompted the JTWC to label it as a "dry typhoon"; rainfall totals on the island ranged from only 40–90 mm (1.5–3.5 in).[2] Despite the extreme winds, little wind-thrown trees or snapped branches were observed. The combination of the winds and light rainfall, however, sprayed saltwater over the island's vegetation, leading to near island-wide loss of leaves. Majority of the local dicots withered and lost their leaves within two days after the storm, while other plants such as palms, cycads and gymnosperms retained their foliage but turned brown.[10] The defoliation led to significant losses for crop farmers;[2] in some locations, the crops did not recover for four years.[11] Along the east coast of Guam, Gay produced a storm surge of 1.2–1.8 m (4–6 ft). The surge reached 3.4 m (11 ft) on Cabras Island in northern Guam, washing sand and water onto coastal roads and breaking a boat from its moorings. The JTWC estimated that damage would have been worse had Typhoon Omar not destroyed the weaker structures three months earlier;[2] little additional damage occurred to the island's capital of Hagåtña.[12] The typhoon destroyed four iron roofs on Tinian Island, located north of Guam. On Saipan to its north, the storm surge destroyed one house and threatened the foundation of several others; twelve families required rescue by emergency workers. The storm caused power outages, and one house sustained fire damage due to candles and kerosene lamps.[2]

Japan

While Gay was becoming extratropical, Okinawa Prefecture experienced heavy rainfall. The highest total was 322 mm (12.7 in), and one station recorded 27 mm (1.1 in) in a ten-minute period. The rains flooded four buildings and inundated crop fields. Rough winds with gusts peaking at 82 km/h (51 mph) caused isolated power outages and the cancellation of two airline flights.[13]

Aftermath

Marshall Islands president Amata Kabua declared nine islands as disaster areas.[2] United States president George H. W. Bush also declared the Marshall Islands a disaster area on December 16.[14] Despite being an independent nation, the Marshall Islands were eligible to the same funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency as a U.S. state or territory.[15] The United States provided a loan of $508,245 (1994 USD) for emergency assistance and to train locals to mitigate future events. After the storm, workers near Majuro planted seeds to regrow the damaged crops.[16]

The rapid succession of typhoons in 1992 caused a significant drop in tourism in Guam.[17] During typhoons Omar and Gay, there was little communication between residents on the island. As a result, the Guam Communications Network was created to facilitate future relief efforts during storms.[18]

A research paper published ten years after the storm suggested that Gay could have been stronger than Typhoon Tip, which attained the lowest barometric pressure ever recorded. While at its peak intensity, Gay registered a rating of 8.0 for nine consecutive hours using the Dvorak technique, indicating sustained wind speeds of at least (315 km/h) 195 mph. In addition, the cyclone had a significantly colder band of clouds around the eye. Typhoon Angela in 1995 presented similar features and could have been stronger than Gay. Neither of the two had direct observations into their eyes, however, making it impossible to confirm such intensity.[19]

See also

- Other storms named Gay

- Typhoon Angela

Notes

- The Joint Typhoon Warning Center is a joint United States Navy – United States Air Force task force that issues tropical cyclone warnings for the western Pacific Ocean and other regions.[1]

- The Japan Meteorological Agency is the official Regional Specialized Meteorological Center for the western Pacific Ocean.[3]

References

- "Joint Typhoon Warning Center Mission Statement". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 2011. Archived from the original on 2007-07-26. Retrieved 2011-11-30.

- 1992 Annual Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. pp. 146–150. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

- Annual Report on Activities of the RSMC Tokyo – Typhoon Center 2000 (PDF) (Report). Japan Meteorological Agency. February 2001. p. 3. Retrieved 2011-11-21.

- "RSMC Best Track Data: 1990–1999" (TXT). Japan Meteorological Agency. 1992-12-25. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

- "Best Track Data for Typhoon Gay (31W)" (TXT). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 2011-04-05. Retrieved 2011-11-29.

- Sherryl Connelly (1999-06-03). "A Lady In Distress ... And The Lover Who Threw Her Cautions To The Wind". New York Daily News. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- "Susan Atkinson, at 49; author and sailor caught in typhoon". Boston Globe. 1992-12-02. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- "Guam, Northern Marianas Brace for Super Typhoon Gay". The Item. Associated Press. 1992-11-22. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- "Typhoon Gay Blows Ashore in Guam". The Deseret News. 1992-11-23. Retrieved 2014-01-18.

- Alexander M. Kerr (2000). "Defoliation of an island (Guam, Mariana Archipelago, Western Pacific Ocean) following a saltspray-laden 'dry' typhoon" (PDF). Journal of Tropical Ecology. 16 (6): 895–901. doi:10.1017/s0266467400001796. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-24. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

- Guam Office of Civil Defense (2011). "Risk Assessment" (PDF). 2011 Guam Hazard Mitigation Plan. URS Corporation. section 5, p. 37. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-07-27. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- "Typhoon passes over Guam". The Daily News. Associated Press. 1992-11-23. Retrieved 2011-12-30.

- Weather Disaster Report (1992-936-13) (Report) (in Japanese). Digital Typhoon. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- "Marshall Islands Typhoon Gay". Federal Emergency Management Agency. 2004-10-18. Archived from the original on 2012-01-06. Retrieved 2012-01-06.

- Compacts of Free Association: Micronesia and the Marshall Islands Face Challenges in Planning for Sustainability, Measuring Progress, and Ensuring Accountability (PDF) (Report). United States Government Accountability Office. December 2006. appendix II, p. 70. GAO-07-163. Retrieved 2011-12-30.

- Project Completion Report of the Emergency Typhoon Rehabilitation Assistance Program Loan and Technical Assistance Completion Report on Disaster Mitigation and Management (PDF) (Report). Asian Development Bank. November 1994. basic data, pp. ii–vi; section II, pp. 1–4; section IV, p. 8; appendix 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-01-18. Retrieved 2011-12-04.

- Hideo Kobayashi, President of Japan Guam Travel Association (August 1993). Testimony of Hideo Kobayashi President, JGTA on Bill Numbers 588 and 589 (PDF) (Transcript). A collection of written testimonies on Bill Numbers 588 and 589 to the Committee on Tourism and Transportation of the Twenty-Second Guam Legislature. Guam Legislature. PDF p. 4. Retrieved 2011-12-02.

- "Mission". Guam Communications Network. Archived from the original on 2011-10-03. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- Karl Hoarau; Gary Padgett & Jean-Paul Hoarau (2004). Have there been any typhoons stronger than Super Typhoon Tip? (PDF). 26th Conference on Hurricanes and Tropical Meteorology. Miami, Florida: American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 2011-12-05.