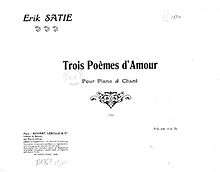

Trois poèmes d'amour

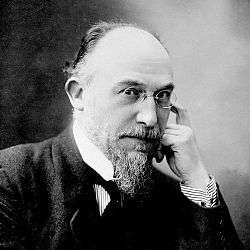

The Trois poèmes d'amour (Three Love Poems) is a 1914 song cycle for voice and piano by Erik Satie. It is the only set of mélodies (French art songs) Satie composed to his own texts.[1] In performance it lasts 2–3 minutes.

Description

The Trois poèmes d'amour is Satie's modern reimagining of Medieval French troubadour songs. He completed the set in Paris between November 20 and December 2, 1914. It consists of three tiny 8-bar tunes:

- 1. Ne suis que grain de sable (Am Only a Grain of Sand)

- 2. Suis chauve de naissance (Am bald from Birth)

- 3. Ta parure est secrète (Your Attire is Discreet)

The music and texts of the poèmes d'amour were written in a deliberately archaic style spiced with offbeat contemporary twists. In the manner of his humoristic piano suites of the period, Satie originally adorned the songs with extramusical commentaries, including a preface which alludes to expressions of courtly love "in ancient times":

- These poems do not discuss the love of Glory, the love of Lucre, the love of Commerce or of

- Geography. No. These poems are poems of the love...of Love; they are simple and devout

- pages wherein are reflected all the tenderness of a virtuous man, very proper in his ways.

- You can listen to them without fear.[2]

Satie's poems are ironic, dispassionate supplications to a seemingly aloof figure of adoration. This muse is suddenly brought into the present-day world in the concluding Ta parure est secrète, in which Satie writes, "My lovely cheerful one/Smokes a cigarette."[3] Satie constructed his rhymes so at the end of each verse he could spoof the vocalized mute "e" in sung French to absurd effect. According to musicologist Patrick Gowers, singers who attempted to tone down this joke infuriated him.[4]

Musically the songs are all in simple ternary form and identical in rhythm, six 8th-notes and a quarter-note, though with subtle harmonic differences. This closely interwoven tripartite structure harkens back to such early Satie works as the Gymnopédies (1888), which have been likened to viewing a sculpture from three different angles. The vocal lines are in the spirit of plainsong[5] and the opening Ne suis que grain de sable is to be sung in the manner of the 11th century Gregorian chant Victimae paschali laudes, which Satie references in the score.[6][7][8][9]

The original notebooks for the poèmes d'amour, unearthed by Robert Orledge, show Satie also wrote additional prefaces for each song and, as a final joke, deliberately numbered the songs incorrectly as 1-3-2.[10]

Satie's motivation for creating this strangely retrospective piece is one of the more intriguing mysteries of his canon. He had written no art songs since the late 1880s, and had largely abandoned his early medieval influences after the Messe des pauvres of 1895.[11] His need to express himself in words as well as music was evident early in his career and found numerous outlets in the 1910s,[12] but this was his lone attempt at lyric poetry. And the subject of love was an odd one for Satie, whose known romantic experience was limited to a youthful fling with the painter Suzanne Valadon in the early 1890s. He ultimately dismissed the emotion as "very comical."[13] There is speculation that Satie may have had a brief affair with the feminist poet Henriette Sauret in 1914, which in turn inspired the song cycle, but this remains unconfirmed.[14]

Performance and publication

Performance of the Trois poèmes d'amour was delayed by the outbreak of World War I. The composer dedicated the cycle to Henri Fabert (1879-1941), a tenor at the Paris Opera, who with Satie at the piano gave the premiere at the Ecole Lucien de Flagny in Paris on April 2, 1916. As the original score was intended for a mezzo-soprano, Satie transposed the vocal lines for Fabert.[15] He then wrote out a neat manuscript copy for mezzo vocalist Jane Bathori, who kept it in her recital repertory for many years.[16][17] Contemporary performances are typically sung by either a mezzo or baritone.

When Rouart, Lerolle & Cie published the score later in 1916, Satie chose to remove all the extramusical verbiage - the prefaces, odd numbering, even the witty playing directions - and allow the songs to stand on their own merits. At the proof stage he added some chromatic grace notes to the piano part of Ta parure est secrète which seem at odds with the work's faux-medieval simplicity, but reinforce its subtly humorous anachronistic tone.[18]

Today the Trois poèmes d'amour rate among Satie's more obscure compositions, although it has had its champions. Patrick Gowers considered it more "individual" than Satie's next two art song cycles, the Trois mélodies (1916) and Quatre petites mélodies (1920).[19] In 1993, longtime Satie enthusiast Friedrich Cerha arranged the set for contralto and chamber orchestra.[20]

Recordings

Gabriel Bacquier with Aldo Ciccolini, piano (EMI, 1970), Elaine Bonazzi and Frank Glazer (Candide, 1970), Marjanne Kweksilber and Reinbert de Leeuw (Harlekijn, 1976, reissued by Philips Classics 2006), Bruno Laplante and Marc Durand (Calliope, 1985), Rainer Pachner and Ramon Walter (Aurophon, 1988), Stephen Varcoe and Graham Johnson (Hyperion, 1993), Anne-Sophie Schmidt with Jean-Pierre Armengaud (Mandala, 1999), Anne-May Krüger and Mike Svoboda (Wergo, 2008), Constanze Brüning and Johannes Cernota (Jaro, 2010).

Notes and references

- Caroline Potter, "Satie as Poet, Playwright and Composer". Chapter 4 of "Erik Satie: Music, Art and Literature", Caroline Potter (ed.), Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2013.

- Potter, "Satie as Poet, Playwright and Composer". Chapter 4 of "Erik Satie: Music, Art and Literature".

- Potter, "Satie as Poet, Playwright and Composer". Chapter 4 of "Erik Satie: Music, Art and Literature".

- Patrick Gowers and Nigel Wilkins, "Erik Satie", "The New Grove: Twentieth-Century French Masters", Macmillan Publishers Limited, London, 1986, p. 142. Reprinted from "The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians", 1980 edition.

- Robert Orledge, "Satie the Composer", Cambridge University Press, 1990, pp. 77-79.

- Leon Guichard, "Erik Satie et la musique Gregorienne," Revue musicale, 15 November 1936, pp. 334-35.

- Rollo H. Myers, "Erik Satie", Dover Publications, Inc., NY, 1968, p. 94. Originally published in 1948 by Denis Dobson Ltd., London.

- Ornella Volta, "A Mammal's Notebook: The Writings of Erik Satie", Atlas Publishing, London, 1996 (reissued 2014), pp. 71, 184, note 24.

- This has been disputed in Orledge, "Satie the Composer", p. 38.

- Orledge, "Satie the Composer", p. 175 and p. 354, note 34.

- Satie authority Caroline Potter wrote that Satie's renewed interest in medievalism in the Trois poèmes d'amour came "seemingly out of the blue", but in fact he had written a Chanson médiévale in 1906 and composed the Fugue litanique, on a plainsong-like subject in Dorian mode, for the suite En habit de cheval (1911). See Potter, "Satie as Poet, Playwright and Composer". Chapter 4 of "Erik Satie: Music, Art and Literature".

- Such as his ironic journalism, notably the Mémoires d'un amnésique (1912-1914), his play Le piège de Méduse (1913), and the extramusical texts for his humoristic piano music (1912-1915), exemplified by Sports et divertissements (1914).

- Ornella Volta (editor), "Satie Seen Through His Letters", Marion Boyars Publishers, London, 1989, p. 47.

- Potter, "Satie as Poet, Playwright and Composer". Chapter 4 of "Erik Satie: Music, Art and Literature".

- Orledge, "Satie the Composer", pp. 308-309.

- Orledge, "Satie the Composer", pp. 308-309.

- Bathori performed the Trois poèmes d'amour with composer-pianist Darius Milhaud in 1937. See Steven Moore Whiting, "Satie the Bohemian", Clarendon Press, 1999 p. 246, note 2.

- Orledge, "Satie the Composer", pp. 308-309.

- Gowers, Wilkins, "Erik Satie", "The New Grove: Twentieth-Century French Masters", p. 142.

- Friedrich Cerha, Trois poèmes d'amour - arrangement pour voix et ensemble, premiered 1993, published 1997. Retrieved from Resources.Ircam at http://brahms.ircam.fr/works/work/31253/