Hairy frog

The hairy frog (Trichobatrachus robustus) is also known as the horror frog or Wolverine frog. It is a Central African species of frog in the family Arthroleptidae. It is monotypic within the genus Trichobatrachus.[2][3] Its common name refers to the somewhat hair-like structures on the body and thighs of the breeding male.

| Hairy frog | |

|---|---|

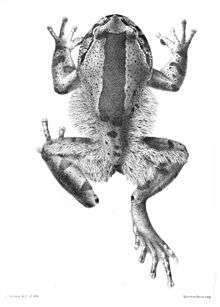

| Male, showing hair-like papillae | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Anura |

| Family: | Arthroleptidae |

| Subfamily: | Astylosterninae |

| Genus: | Trichobatrachus Boulenger, 1900 |

| Species: | T. robustus |

| Binomial name | |

| Trichobatrachus robustus Boulenger, 1900 | |

Description

Males are about 10–13 cm (4–5 in) long from snout to vent, while females are 8–11 cm (3–4.5 in).[4] The large head is broader than long, with a short rounded snout. The former have a paired internal vocal sac and three short ridges of small black spines along the inner surface of the first manual digit. Breeding males also develop – somewhat hair-like – dermal papillae that extend along the flanks and thighs. These contain arteries and are thought to increase the surface area for the purpose of absorbing oxygen (comparably to external gills of the aquatic stage), which is useful as the male stays with his eggs for an extended period of time after they have been laid in the water by the female.

The species is terrestrial, but returns to the water for breeding, where egg masses are laid onto rocks in streams. The quite muscular tadpoles are carnivorous and feature several rows of horned teeth. Adults feed on slugs, myriapods, spiders, beetles and grasshoppers.

The hairy frog is also notable in possessing retractable "claws" (though unlike true claws, they are made of bone, not keratin), which it may project through the skin, apparently by intentionally breaking the bones of the toe.[5] In addition, the researchers found a small bony nodule nestled in the tissue just beyond the frog's fingertip. When sheathed, each claw is anchored to the nodule with tough strands of collagen, but, as Gerald Durrell[6] discovered firsthand, when the frog is grabbed or attacked, the frog breaks the nodule connection and forces its sharpened bones through the skin.[7]

This is probably a defensive behavior. Although a retraction mechanism is not known, it has been hypothesized that the claws later retract passively, while the damaged tissue is regenerated.

Amphibian researcher and biologist David Wake of the University of California, Berkeley, says that this type of weaponry appears to be unique in the animal kingdom, (although the Otton Frog possesses a similar "spike" in its thumb).[8] Also David Cannatella, a herpetologist at the University of Texas, Austin, questions whether the bony protrusions are meant for fighting. They could allow a frog's feet "to get a better grip on whatever rocky habitat they might be in," he says.[9]

Distribution

It is found in Cameroon, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Nigeria, and possibly Angola. Its natural habitats are subtropical or tropical moist lowland forests, rivers, arable land, plantations, and heavily degraded former forest.

Conservation status

T. robustus is threatened by habitat loss, but is not considered endangered.

Relation with humans

This species is roasted and eaten in Cameroon. They are hunted with long spears or machetes. The Bakossi people traditionally believed that the frogs fall from the sky and, when eaten, it would help childless couples become fertile.[10]

References

- Amiet, J.-L. & Burger, M. (2004). "Trichobatrachus robustus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2004. Retrieved 26 June 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Trichobatrachus ". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- Frost, Darrel R. (2013). "Trichobatrachus Boulenger, 1900". Amphibian Species of the World 5.6, an Online Reference. American Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- Halliday, T. (2016). The Book of Frogs: A Life-Size Guide to Six Hundred Species from around the World. University Of Chicago Press. p. 436. ISBN 978-0226184654.

- "'Horror frog' breaks own bones to produce claws". NewScientist.com. 2008. Archived from the original on 2015-06-13. Retrieved 2017-08-29.

- Durrell, G. The Bafut Beagles Rupert Hart-Davis, 1954; chapter 5.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-02-15. Retrieved 2019-02-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-03-02. Retrieved 2014-03-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "News". Science - AAAS. 30 October 2014. Archived from the original on 15 February 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- Legrand N. Gonwouo & Mark-Oliver Rödel (20 February 2008). "The importance of frogs to the livelihood of the Bakossi people around Mount Manengouba, Cameroon, with special consideration of the Hairy Frog, Trichobatrachus robustus". Salamandra. 44 1: 23–34. ISSN 0036-3375. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- AmphibiaWeb: Trichobatrachus robustus

- New Scientist news service: 'Horror frog' breaks own bones to produce claws Retrieved on June 9, 2008.

- Blackburn, David C.; Hanken, James & Jenkins, Farish A. Jr. (2008): Concealed weapons: erectile claws in African frogs. biology letters (published online). doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0219 – PDF

External links

![]()

![]()

- Hairy Frog – Trichobatrachus robustus, The BioFresh Cabinet of Freshwater Curiosities.

- "Hairy frog" at the Encyclopedia of Life