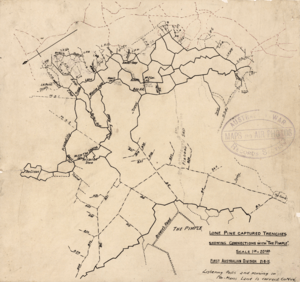

Trench map

A Trench map shows trenches dug for use in war. This article refers mainly to those produced by the British during the Great War, 1914–1918 although other participants made or used them..

For much of the Great War, trench warfare was almost static, giving rise to the need for large scale maps for attack, defence and artillery use. Initially, British trench maps showed the German trench systems in detail, but only the British Front line. Later in the war, more of the British trenches were shown. The only British maps that showed full detail of both sides were the secret editions, usually marked "Not to be taken beyond Brigade HQ" for fear of their falling into enemy hands.

Scale and availability

The majority of trench maps were to a scale of 1:10,000 or 1:20,000, although trench maps also frequently appeared on a scale of 1:5,000 (maps printed on a large scale such as 1:5,000, were generally meant for use in assaults). In addition, the British army also printed maps on scales smaller than 1:20,000, such as 1:40,000 and 1:100,000, but these maps seldom showed trenches. Therefore, they do not typically count as "trench maps," although by 1918 certain of the 1:40,000 maps did show trenches. As a rule of thumb, the infantry preferred 1:10,000 and the field artillery 1:20,000, with the heavy artillery and staff officers making primary use of the 1:40,000 maps. In the 'Report on Survey on the Western Front 1914-1918', published in 1920, Colonel E.M. Jack wrote "The 1:20,000 was the map commonly used by the Artillery, and as trenches could be shown on it in sufficient detail to be of use to the infantry it was the most useful scale of all, and the one that could least easily be dispensed with." Colonel Jack was a key figure in Great War cartography.

At the start of the war there were no trench maps--trench warfare did not develop until late 1914, and the British army did not possess in the Summer of 1914 the logistical and technical support that making trench maps would have required. The British Army went to war with maps more suited to a "war of movement", i.e. small scale maps, of a scale just about adequate for marching. Once the line had become static after the Battle of the Aisne and the Race for the Sea, the need for accurate, detailed maps of the new trench networks became urgent.

The earliest trench maps dating from 1915 were often made from enlargements of French and Belgian maps of variable quality. Some re-surveying of the front was carried out when it was found that such enlargements were not sufficiently precise. Precision was paramount to the artillery, especially later in the war when techniques were developed to "shoot from the map".

These first trench maps, used until the Summer of 1915, also suffered from a lack of standardization. In the absence of a single, theatre-wide format for trench maps, some rather idiosyncratic patterns came into being in these early days of trench warfare. For example, on the British 1st Army Front, troops used the notorious maps that the intelligence officer Col. Charteris favored, which actually printed the North on the bottom and the East on the left-hand side of the map! In addition, the inverted Charteris maps lacked an over-printed grid with hash-marks, so that individual targets required individual target reference numbers. The British Army had to fight two of the largest early battles of the war, those of Aubers Ridge and Festubert, using these wholly unsatisfactory maps.

Partly in response to the evident deficiencies of such maps, the British Army put into use, starting in July 1915, the "Regular Series" trench map. These Regular Series maps, printed in Britain, did much to improve the situation (all 1:10,000 scale maps in this series, printed by the Geographical Section of the General Staff, bear the GSGS number 3062; 1:20,000 scale maps of this series bear the GSGS number 2742; maps of this series were almost invariably backed with linen, greatly improving their durability). Even after the Regular Series came into use in the Summer of 1915, however, local editions of maps, of different formats and printed at the front, remained in use, and did so throughout the war.

Confusion

.jpg)

A trench map consisted of a base map that showed roads, towns, rivers, forests and so on, over-printed with trenches; red for German, blue for British. Early in 1918 these colours were reversed to come into line with French practice, so that red would henceforth refer to British trenches and blue to German ones. To add to the confusion, some trench maps were printed with all the trenches of the same colour. A base map usually had an edition number followed by a letter, so a map marked 6C had an edition 6 base map and the trench over print of edition C. This system was not strictly adhered to, since sometimes, two maps with the same number and letter can be found but with different detail and different dates. On many of the maps, the words "Trenches corrected to" are followed by either a single date or a separate date for British and German trenches.

Trench maps were updated from aerial photographs and intelligence reports although sometimes captured German maps were used as a source of detail. The use of aerial photography in cartography developed to an enormous degree during the Great War. Before 1914, experiments had been made and papers written on the subject but little was available to the Army for actual use. By the end of the war, it was possible to produce accurate photographs and to transcribe detail to accurate maps as well as the assessment of height of the land forms.

Printing techniques

Most of the maps were printed in England or well behind the lines as the printing presses were not easy to move at short notice should an attack by the Germans be successful. Some small sheets were made nearer the front by other techniques but the regular series trench maps were printed using lithography on large presses by very skilled printers. Some of these maps were printed from zinc plates but many were printed from lithographic limestone plates.

An estimated 32 million maps were printed in the Great War but most have been destroyed. Many are in private hands but important collections are available for public viewing at the Imperial War Museum in London and The National Archive (TNA) at Kew. Digital versions are also becoming available as interest in the Great War increases.

References

LinesMan. 750x GPS compatible digital 1:10,000 scale trench maps available from Great War Digital. ISBN 0-9554546-0-3

Textbook of Topographical and Geographical Surveying by Colonel C.F Close, C.M.G, R.E. Director General of the Ordnance Survey

Report on Survey on the Western front, 1914–1918, Published in 1920, HMSO. By Colonel E.M. Jack

Artillery's Astrologers, A History of British Survey and Mapping on the Western Front 1914-1918 by Peter Chasseaud, ISBN 978-0-9512080-2-1

Trench Maps - A Collectors Guide (1986) - by Peter Chasseaud, ISBN 978-0-9512080-0-7 (Out of print)

Topography of Armageddon - A British Trench Map Atlas of the Western Front (1991, reprinted 1998) - by Peter Chasseaud, ISBN 978-0-9512080-1-4<