Treasury Enterprise Architecture Framework

Treasury Enterprise Architecture Framework (TEAF) was an Enterprise architecture framework for treasury, based on the Zachman Framework. It was developed by the US Department of the Treasury and published in July 2000.[2] May 2012 this framework has been subsumed by evolving Federal Enterprise Architecture Policy as documented in "The Common Approach to Federal Enterprise Architecture".[3]

The material presented here is obsolete and only useful for historical reference and is not the current policy in use by the Department of the Treasury.

Overview

The Treasury Enterprise Architecture Framework (TEAF) an architectural framework that supports Treasury's business processes in terms of products. This framework guides the development and redesign of the business processes for various bureaus in order to meet the requirements of recent legislation in a rapidly changing technology environment. The TEAF prescribes architectural views and delineates a set of notional products to portray these views.[1]

The TEAF describes provides:[1]

- Guidance to Treasury bureaus concerning the development and evolution of information systems architecture,

- A unifying concept, common principles, technologies, and standards for information systems, and

- A template for the development of the Enterprise Architecture.

The TEAF's functional, information and organizational architecture views collectively model the organizations processes, procedures, and business operations. By grounding the architecture in the business of the organization, the TEAF defines the core business procedures and enterprise processes. Through its explicit models, a TEAF-based architecture enables the identification and reasoning of enterprise- and system-level concerns and investment decisions.[1]

History

The Treasury Enterprise Architecture Framework (TEAF) is derived from earlier treasury models, such as the US Treasury model (TISAF) released 1997, and the Federal Enterprise Architecture Framework (FEAF), released in 1999.[4] The first version of the TEAF was released July 2000.

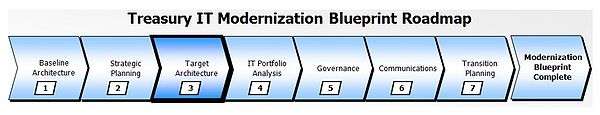

In the new millennium the Treasury Enterprise Architecture Framework (TEAF) has developed into the Treasury Enterprise Architecture (TEA), which aims to establish a roadmap for the modernization and optimization of the U.S. Treasury Department's business processes and IT environment. The Treasury Enterprise Architecture will provide a framework to guide IT investment planning, streamline systems, and ensure that IT programs align with business requirements and strategic goals.[6]

TEAF Topics

Enterprise Architecture

Effective management and strategic decision making, especially for information technology (IT) investments, require an integrated view of the enterprise—understanding the interrelationships among the business organizations, their operational processes, and the information systems that support them. An Enterprise Architecture formalizes the identification, documentation, and management of these interrelationships, and supports the management and decision processes. The Enterprise Architecture provides substantial support for evolution of an enterprise as it anticipates and responds to the changing needs of its customers and constituents. The Enterprise Architecture is a vital part of the enterprise's decision-making process, and will evolve along with the enterprise's mission.[2]

The TEAF has been designed to help both the bureaus and the Department develop and maintain their Enterprise Architectures. The TEAF aims to establish a common Enterprise Architecture structure, consistent practices, and common terminology; and to institutionalize Enterprise Architecture governance across the Department. This architectural consistency will facilitate integration, information sharing, and exploitation of common requirements across Treasury.[2]

Enterprise Architecture Framework

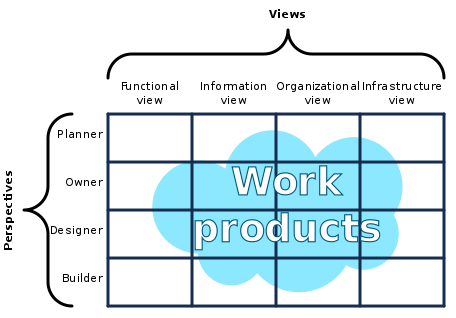

The purpose of the Enterprise Architecture Framework is to provide a structure for producing an Enterprise Architecture (EA) and managing Enterprise Architecture assets. To reduce the complexity and scope of developing and using an Enterprise Architecture, it must be subdivided so that portions may be used independently or built incrementally in separate projects. The TEAF subdivides an Enterprise Architecture by:[2]

- Views

- Perspectives

- Work products

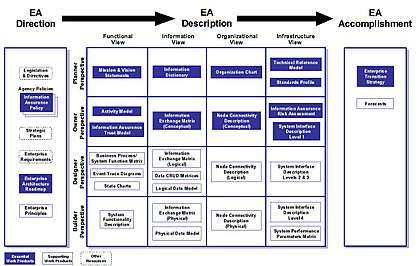

The TEAF identifies, as shown in the figure, resources and work products that provide direction for EA development, work products constituting the EA description, and work products documenting how to accomplishment an EA implementation. The resources and work products for EA direction and accomplishment are not part of the EA description itself, but are developed and applied during the overall enterprise life cycle. The TEAF Matri, organizes the subdivisions of the EA description and demonstrates the relationships among them. The following sections describe the subdivisions of the EA and their relationships to the TEAF Matrix.[2]

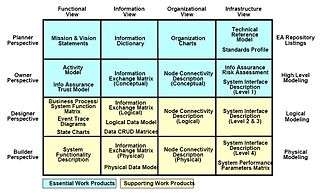

TEAF Matrix of Views and Perspectives

The TEAF Matrix is a simplified portrayal of an EA structure to aid in understanding important EA aspects from various vantage points (views and perspectives). The TEAF Matrix aims to provide a simple, uniform structure to an entire framework. As depicted in the figure, the TEAF Matrix consists of four architectural views (Functional, Information, Organizational, and Infrastructure), which are shown as columns, and four perspectives (Planner, Owner, Designer, and Builder), which appear as rows. The TEAF Matrix is a four-by-four matrix with a total of 16 cells. The views and perspectives are described in the following sections.[2]

When an EA description work product is shown within one cell of the TEAF Matrix, it means that the main vantage points for developing that work product correspond to that column (view) and row (perspective). However, information from other views (and sometimes other perspectives) is needed to produce a work product. Not all cells must be "filled-in" by producing an associated work product. Each bureau must define in its EA Roadmap its plans for producing and using an EA to match its needs.[2]

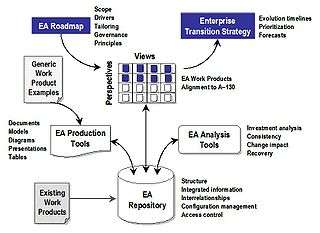

Enterprise Life Cycle activities

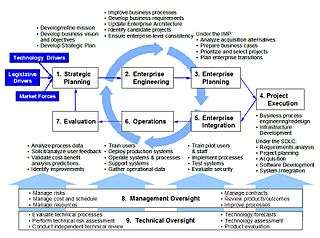

An Enterprise Life Cycle integrates the management, business, and engineering life cycle processes that span the enterprise to align its business and IT activities. Enterprise Life Cycle refers generally to an organization's approach for managing activities and making decisions during ongoing refreshment of business and technical practices to support its enterprise mission. These activities include investment management, project definition, configuration management, accountability, and guidance for systems development according to a System Development Life Cycle (SDLC). The Enterprise Life Cycle applies to enterprise-wide planning activities and decision making. By contrast, a System Development Life Cycle generally refers to practices for building individual systems. Determining what systems to build is an enterprise-level decision.[2]

The figure on the left depicts notional activities of an Enterprise Life Cycle methodology. Within the context of this document, Enterprise Life Cycle does not refer to a specific methodology or a specific bureau's approach. Each organization needs to follow a documented Enterprise Life Cycle methodology appropriate to its size, the complexity of its enterprise, and the scope of its needs.[2]

Products

The TEAF provides a unifying concept, common terminology and principles, common standards and formats, a normalized context for strategic planning and budget formulation, and a universal approach for resolving policy and management issues. It describes the enterprise information systems architecture and its components, including the architectures purpose, benefits, characteristics, and structure. The TEAF introduces various architectural views and delineates several modeling techniques. Each view is supported with graphics, data repositories, matrices, or reports (i.e., architectural products).[1]

The figure shows a matrix with four views and four perspectives. Essential products are shown across the top two rows of the matrix. It is notable that the TEAF includes an Information Assurance Trust model, the Technical Reference Model, and standards profiles as essential work products. These are not often addressed as critical framework components. One of these frameworks should provide a means to logically structure and organize the selected EA products. Now, in order to effectively create and maintain the EA products, a toolset should be selected.[1]

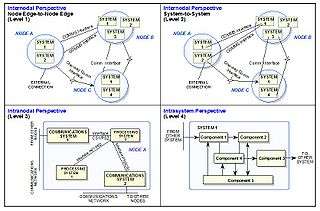

System Interface Description

The System Interface Description (SID) links together the Organizational and Infrastructure Views by depicting the assignments of systems and their interfaces to the nodes and needlines described in the Node Connectivity Description. The Node Connectivity Description for a given architecture shows nodes (not always defined in physical terms), while the System Interface Description depicts the systems corresponding to the system nodes. The System Interface Description can be produced at four levels, as described below. Level 1 is an essential work product, while Levels 2, 3, and 4 are supporting work products.[2]

The System Interface Description identifies the interfaces between nodes, between systems, and between the components of a system, depending on the needs of a particular architecture. A system interface is a simplified or generalized representation of a communications pathway or network, usually depicted graphically as a straight line, with a descriptive label. Often, pairs of connected systems or system components have multiple interfaces between them. The System Interface Description depicts all interfaces between systems and/or system components that are of interest to the architect.[2]

The graphic descriptions and/or supporting text for the System Interface Description should provide details concerning the capabilities of each system. For example, descriptions of information systems should include details concerning the applications present within the system, the infrastructure services that support the applications, and the means by which the system processes, manipulates, stores, and exchanges data.[2]

See also

- Department of Defense Architecture Framework.

- Federal Enterprise Architecture

- Conceptual schema

References

- FEA Consolidated Reference Model Document Archived 2010-07-05 at the Wayback Machine. whitehouse.gov May 2005.

- US Department of the Treasury Chief Information Officer Council (2000). Treasury Enterprise Architecture Framework Archived 2009-03-18 at the Wayback Machine. Version 1, July 2000.

- whitehouse.gov (May 12, 2012)The Common Approach to Federal Enterprise Architecture. Accessed January 10, 2013

- Jaap Schekkerman (2003). How to Survive in the Jungle of Enterprise Architecture Frameworks. p.113

- Standards and Configuration Management Team (SCMT) of the Treasury Enterprise Architecture Sub-Council (TEAC) (2007). Treasury Technical Standards Profile Archived 2008-12-10 at the Wayback Machine. May 2007

- E-Government Archived 2008-12-10 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Treasury Department, accessed 09 Dec 2008.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Treasury Enterprise Architecture Framework. |

- U.S. Treasury - Office of the CIO homepage.

- Other Architectures and Frameworks, The Open Group 1999-2006.