Tourniquet

A tourniquet is a device which applies pressure to a limb or extremity in order to limit – but not stop – the flow of blood. It may be used in emergencies, in surgery, or in post-operative rehabilitation. A simple tourniquet can be made from a stick and a rope (or leather belt), but the use of makeshift tourniquets has been reduced over time due to their ineffectiveness compared to a commercial and professional tourniquet. This may stem the flow of blood, but side effects such as soft tissue damage and nerve damage may occur.

Types

There are three types of tourniquets: surgical tourniquets, emergency tourniquets, and rehabilitation tourniquets.

Surgical tourniquets

Silicone ring tourniquets, or elastic ring tourniquets, are self-contained mechanical devices that do not require any electricity, wires or tubes. The tourniquet comes in a variety of sizes. To determine the correct product size, the patient's limb circumference at the desired occlusion location should be measured, as well as their blood pressure to determine the best model.[1] Once the correct model is selected, typically two sterile medical personnel will be needed to apply the device. Unlike with the pneumatic tourniquet, the silicone ring tourniquet should be applied after the drapes have been placed on the patient. This is due to the device being completely sterile.[2] The majority of the devices require a two-man operation (with the exception of the extra large model):

- One person is responsible for holding the patient's limb, the other will place the device on the limb (with the extra-large there are two people needed).

- Application:

- Place the elastic ring tourniquet on the hand/foot. Take care to ensure that all the fingers/toes are enclosed within the device.

- The handles of the tourniquet should be positioned medial-lateral on the upper extremity or posterior-anterior on the lower extremity.

- The person applying the device should start rolling the device while the individual responsible for the limb should hold the limb straight and maintain axial traction.

- Once the desired occlusion location is reached, the straps can be cut off or tied just below the ring.

- A window can be cut or the section of stockinet can be completely removed.

- Once the surgery is completed the device is cut off with a supplied cutting card.

The elastic ring tourniquet follows similar recommendations noted for pneumatic tourniquet use:

- It should not be used on a patient's limb for more than 120 minutes.

- The tourniquet should not be placed on the ulnar/peroneal nerve.

- The silicone ring device cannot be used on patients with blood problems such as DVT, edema, etc.

- A patient suffering from skin lesions or a malignancy should use this type of tourniquet.[3]

Emergency tourniquets

Silicone ring auto-transfusion tourniquet

The silicone ring auto-transfusion tourniquet (SRT/ATT/EED), or surgical auto-transfusion tourniquet (HemaClear), is a simple to use, self-contained, mechanical tourniquet that consists of a silicone ring, stockinet, and pull straps that results in the limb being exsanguinated and occluded within seconds of application.[4] The tourniquet can be used for limb procedures in the operating room, or in emergency medicine as a means to stabilize a patient until further treatment can be applied.[5]

Combat application tourniquet

The combat application tourniquet (CAT) was developed by Ted Westmoreland. It is used by the U.S. and coalition militaries to provide soldiers a small and effective tourniquet in field combat situations. It is also used the UK by NHS ambulance services, along with some UK fire and rescue services. The unit utilizes a windlass with a locking mechanism and can be self-applied. The CAT has been adopted by military and emergency personnel around the world.[6]

History

During Alexander the Great’s military campaigns in the fourth century BC, tourniquets were used to stanch the bleeding of wounded soldiers.[7] Romans used them to control bleeding, especially during amputations. These tourniquets were narrow straps made of bronze, using only leather for comfort.[8]

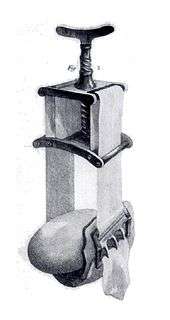

In 1718, French surgeon Jean Louis Petit developed a screw device for occluding blood flow in surgical sites. Before this invention, the tourniquet was a simple garrot, tightened by twisting a rod (thus its name tourniquet, from tourner = to turn).

In 1785 Sir Gilbert Blane advocated that, in battle, each Royal Navy sailor should carry a tourniquet:

It frequently happens that men bleed to death before assistance can be procured, or lose so much blood as not to be able to go through an operation. In order to prevent this, it has been proposed, and on some occasions practised, to make each man carry about him a garter, or piece of rope yarn, in order to bind up a limb in case of profuse bleeding. If it be objected, that this, from its solemnity may be apt to intimidate common men, officers at least should make use of some precaution, especially as many of them, and those of the highest rank, are stationed on the quarter deck, which is one of the most exposed situations, and far removed from the cockpit, where the surgeon and his assistants are placed. This was the cause of the death of my friend Captain Bayne, of the Alfred, who having had his knee so shattered with round shot that it was necessary to amputate the limb, expired under the operation, in consequence of the weakness induced by loss of blood in carrying him so far. As the Admiral on these occasions allowed me the honour of being at his side, I carried in my pocket several tourniquets of a simple construction, in case that accidents to any person on the quarter deck should have required their use.[9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17]

In the 2000s, the silicon ring tourniquet, or elastic ring tourniquet, was developed by Noam Gavriely, a professor of medicine and former emergency physician.[18][19] The tourniquet consists of an elastic ring made of silicone, stockinet, and pull straps made from ribbon that are used to roll the device onto the limb. The silicone ring tourniquet exsanguinates the blood from the limb while the device is being rolled on, and then occludes the limb once the desired occlusion location is reached.[1] Unlike the historical mechanical tourniquets, the device reduces the risk of nerve paralysis.[20][21] The surgical tourniquet version of the device is completely sterile, and provides improved surgical accessibility due to its narrow profile that results in a larger surgical field. It has been found to be a safe alternative method for most orthopedic limb procedures, but it does not completely replace the use of contemporary tourniquet devices.[22][23] More recently the silicone ring tourniquet has been used in the fields of emergency medicine and vascular procedures.[19][24]

After World War II, the US military reduced use of the tourniquet because the time between application and reaching medical attention was so long that the damage from stopped circulation was worse than that from blood loss. Since the beginning of the 21st century, US authorities have resuscitated its use in both military and non-military situations because treatment delays have been dramatically reduced. The Virginia State Police and police departments in Dallas, Philadelphia and other major cities provide tourniquets and other advanced bandages. In Afghanistan and Iraq, only 2 percent of soldiers with severe bleeding died compared with 7 percent in the Vietnam War, in part because of the combination of tourniquets and rapid access to doctors. Between 2005 and 2011, tourniquets saved 2,000 American lives from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.[25] In civilian use, emerging practices include transporting tourniquetted patients even before emergency responders arrive and including tourniquets with defibrillators for emergency use.

See also

References

- Drosos, GI; Ververidis, A; Stavropoulos, NI; Mavropoulos, R; Tripsianis, G; Kazakos, K (June 2013). "Silicone ring tourniquet versus pneumatic cuff tourniquet in carpal tunnel release: a randomized comparative study". J Orthop Traumatol. 14 (2): 131–5. doi:10.1007/s10195-012-0223-x. PMC 3667358. PMID 23361654.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Thompson, SM; Middleton, M; Farook, M; Cameron-Smith, A; Bone, S; Hassan, A (November 2011). "The effect of sterile versus non-sterile tourniquets on microbiological colonisation in lower limb surgery". The Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 93 (8): 589–90. doi:10.1308/147870811X13137608455334. PMC 3566682. PMID 22041233.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Norman, D; Greenfield, I; Ghrayeb, N; Peled, E; Dayan, L (December 2009). "Use of a new exsanguination tourniquet in internal fixation of distal radius fractures". J Orthop Traumatol. 13 (4): 173–5. doi:10.1097/BTH.0b013e3181b56187. PMID 19956041.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- HemaClear Instructional Video for the Orange Model (Large) on YouTube

- EmergencyEED

- Reference: "Testing of Battlefield Tourniquets" by Dr. Thomas Walters, US Army Institute of Surgical Research, presented at Advanced Technology Applications for Combat Casualty Care 2004 (ATACCC) Conference, published in the Conference Proceedings, Aug 16-18 2004, St. Petersburg, FL. http://www.usaccc.org/ataccc/index.jsp

- SCHMIDT, MICHAEL S. (January 19, 2014). "Reviving a Life Saver, the Tourniquet". New York Times.

- "Thigh tourniquet, Roman, 199 BCE-500 CE". sciencemuseum.org.uk. July 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-19.

- Blane, Gilbert (1785). Observations on the diseases incident to seamen. London: Joseph Cooper; Edinburgh: William Creech. pp. 498–499.

- Feldman, Viktor; Biadsi, Ahmad; Slavin, Omer; Kish, Benjamin; Tauber, Israel; Nyska, Meir; Brin, Yaron S. (December 2015). "Pulmonary Embolism After Application of a Sterile Elastic Exsanguination Tourniquet". Orthopedics. 38 (12): e1160–1163. doi:10.3928/01477447-20151123-08. ISSN 1938-2367. PMID 26652340.

- Middleton, K. W. D.; Varian, J. P. (1974-05-01). "Tourniquet Paralysis1". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Surgery. 44 (2): 124–128. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.1974.tb06402.x. ISSN 1445-2197. PMID 4533458.

- McLaren, A. C.; Rorabeck, C. H. (March 1985). "The pressure distribution under tourniquets". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 67 (3): 433–438. doi:10.2106/00004623-198567030-00014. ISSN 0021-9355. PMID 3972869.

- Klenerman, L. (November 1962). "The tourniquet in surgery". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume. 44-B (4): 937–943. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.44B4.937. ISSN 0301-620X. PMID 14042193.

- Richard, RL (1951). "Ischaemic lesions of peripheral nerves: a review". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 14 (2): 76–87. doi:10.1136/jnnp.14.2.76. PMC 499577. PMID 14850993.

- Fletcher, I. R.; Healy, T. E. (November 1983). "The arterial tourniquet". Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 65 (6): 409–417. ISSN 0035-8843. PMC 2494408. PMID 6357039.

- MOLDAVER, JOSEPH (1954-02-01). "Tourniquet Paralysis Syndrome". Archives of Surgery. 68 (2): 136–44. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1954.01260050138002. ISSN 0096-6908. PMID 13123650.

- The Tourniquet Manual — Principles and Practice | Leslie Klenerman | Springer. Springer. 2003. ISBN 9781852337063.

- "Unit of Physiology and Biophysics- Noam Gavriely".

- Tang, DH; Olesnicky, BT; Eby, MW; Heiskell, LE (6 December 2013). "Auto-transfusion tourniquets: the next evolution of tourniquets". Open Access Emergency Medicine. 2013 (5): 29–32. doi:10.2147/OAEM.S39042. PMC 4806816. PMID 27147871.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Mohan, A; Baskaradas, A; Solan, M; Magnussen, P (March 2011). "Pain and paraesthesia produced by silicone ring and pneumatic tourniquets". J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 36 (3): 215–8. doi:10.1177/1753193410390845. PMID 21131688.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Gavriely, N (May 2010). "Surgical Tourniquets in Orthopaedics". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 92A (5): 1318–1322. PMID 20439692.

- Demirkale, I; Tecimel, O; Sesen, H; Kilicarslan, K; Altay, M; Dogan, M (29 October 2013). "Nondrainage Decreases Blood Transfusion Need and Infection Rate in Bilateral Total Knee Arthroplasty". J Arthroplasty. 29 (5): 993–997. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2013.10.022. PMID 24275263.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Drosos, GI; Ververidis, A; Mavropoulos, R; Vastardis, G; Tsioros, KI; Kazakos, K (September 2013). "The silicone ring tourniquet in orthopaedic operations of the extremities". Surg Technol Int. 23: 251–7. PMID 23860930.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Ladenheim, E; Krauthammer, J; Agrawal, S; Lum, C; Chadwick, N (April–June 2013). "A sterile elastic exsanguination tourniquet is effective in preventing blood loss during hemodialysis access surgery". J Vasc Access. 14 (2): 116–9. doi:10.5301/jva.5000107. PMC 6159822. PMID 23080335.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Trauma medicine has learned lessons from the battlefield". The Economist. 12 October 2017.

External links

| Look up tourniquet in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tourniquets. |

- Klenerman, L. (1962). "The tourniquet in surgery" (PDF). The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 44 (4): 937–943. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.44B4.937. PMID 14042193.

- Torres, M. R., MD. (2019, May 06). CoTCCC Recommended Devices and Adjuncts - 06 May 2019. Retrieved from https://tactical-medicine.com/blog/news/cotccc-recommended-devices-and-adjuncts-06-may-2019