Torghut

The Torghut (Mongolian: Торгууд,ᠲᠤᠷᠭᠣᠣᠠ,Torguud, "Guardsman" or "the Silks") are one of the four major subgroups of the Four Oirats. The Torghut nobles traced its descent to the Keraite ruler Tooril also many Torghuts descended from the Keraites.

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 106,000[1] | |

| 14,176[2] | |

| Languages | |

| Torgut dialect of Oirat | |

| Religion | |

| Tibetan Buddhism, Shamanism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Mongols, especially Oirats | |

History

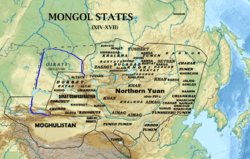

They might have been kheshigs of the Great Khans before Kublai Khan. The Torghut clan first appeared as an Oirat group in the mid-16th century. After the collapse of the Four Oirat Alliance, the majority of the Torghuts under Kho Orluk separated from other Oirat groups and moved west to the Volga region in 1630, forming the core of the Kalmyks. A few Torghut nobles followed Toro Baikhu Gushi Khan to Qinghai Lake (Koke Nuur), becoming part of the so-called Upper Mongols. In 1698, 500 Torghuts went on pilgrimage to Tibet but were unable to return. Hence, they were resettled in Ejin River by the Kangxi Emperor of China's Qing dynasty. In 1699 15,000 Torghut households returned from the Volga region to Dzungaria where they joined the Khoits. After the fall of the Dzungar Khanate, one of their princes, Taiji Shyiren, fled west to the Volga region with 10,000 families in 1758. The name Torghut probably originates from the Mongolian word "torog" meaning "silk."

Due to harsh treatment by Russian governors, most Torghuts eventually migrated back to Dzungaria and western Mongolia, departing en masse on January 5, 1771.[3] While the first phase of their movement became the Old Torghuts, the Qing called the later Torghut immigrants "New Torghut". The size of the departing group has been variously estimated between 150,000 and 400,000 people, with perhaps as many as six million animals (cattle, sheep, horses, camels and dogs).[4] Beset by raids, thirst and starvation, approximately 85,000 survivors made it to Dzungaria, where they settled near the Ejin River with the permission of the Qing Emperor.[4] The Torghuts were coerced by the Qing into giving up their nomadic lifestyle and to take up sedentary agriculture instead as part of a deliberate policy by the Qing to enfeeble them.

The Kalmuks on the river Tekes had not sent the assistance demanded by the Governor, being angry that he had not assisted them when they had been attacked a few months before by the Kara-Kirghiz. At last, however, when their great temple on the Ili had been plundered by the Dungans, their Lama excited them to revenge. They therefore marched down to near Ili and signally defeated the insurgents, who after that dared no longer show themselves in the vicinity. The harvest was now ripe, and the grain was greatly needed by the suffering garrison and town population, but no one dared to reap it for fear of the Dungans. The Governor therefore ordered the Kalmuks to gather the harvest, but, as they were nomads who despised agriculture, they refused, and when threats were offered, they all decamped, and no persuasions could bring them back. After their departure the Dungans immediately resumed operations. Of the frightful position of affairs in the fortress, we learn something from Colonel Reinthal, who was there in July and September 1865, to obtain information on the position. It is much to be regretted that the Russian Government did not act upon the information contained in his reports, and either give some active support to the Chinese authorities, or itself occupy the country to prevent bloodshed. The scarcity of provisions in Ili became such that the Governor at last saw himself obliged to dismiss his last auxiliaries, the Thagor Kalmuks. In the meantime both Solons and Sibos were being attacked and plundered, and were obliged to make peace with the insurgents, so that only Ili, Khorgos, Losigun, and Suidun, remained in the hands of the Mantchus. Ili was now entirely surrounded, and it was resolved to reduce it by famine.[5][6][7][8]

A group of around 70,000 Torghuts were left behind in Russia, since (according to legend) the Volga River was not frozen and they could not cross it to join their comrades.[4] This group became known as the Kalmyk, or "remnant",[4] although the name may predate these events. However, Muslims called the Kalmyks before. In any case, the remnant population double their numbers by 1930.[4] Torghut-Kalmyk archers under the command of the notable Russian general Mikhail Kutuzov clashed with the French army of the legendary Napoleon in 1812.[9]

In 1906, the Qing put western Mongolia's New Torghuts under the Altai district. One New Torghut prince opposed independence in Mongolia and fled to Xinjiang in 1911-12. However, the others were reincorporated into Mongolia's far western Khovd Province. Torghut forces assisted the Russians in the Soviet Invasion of Xinjiang.

An exhibition in memorial to the Torghut exodus from the Volga to the Qing Empire is found at the Potala Palace, Chengde.

Language

Modern notable Torghuts in Mongolia

- Shiileg, a hero of Mongolia

- Badam, a hero of Mongolia

- Purevjal, a famous Mongolian singer

- Luvsan, a hero of Labor of Mongolia

- Otgontsagaan, a hero of Labor of Mongolia

- Batlai, a hero of Labor of Mongolia

- Tuvshin, a hero of Labor of Mongolia

- Baadai, a hero of Labor of Mongolia

References

- Dunnell, Ruth W.; Elliott, Mark C.; Foret, Philippe; Millward, James A (2004). New Qing Imperial History: The Making of Inner Asian Empire at Qing Chengde. Routledge. ISBN 1134362226. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Millward, James A. (1998). Beyond the Pass: Economy, Ethnicity, and Empire in Qing Central Asia, 1759-1864 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804729336. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Perdue, Peter C (2009). China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia (reprint ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674042026. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Ram Rahul-March of Central Asia Indus Publishing, 2000 ISBN 81-7387-109-4

- Johan Elverskog-Our Great Qing:The Mongols, Buddhism and the State in Late Imperial China ISBN 0-8248-3021-0

- Wang Jinglan, Shao Xingzhou, Cui Jing et al. Anthropological survey on the Mongolian Tuerhute tribe in He shuo county, Xinjiang Uigur autonomous region // Acta Anthropologica Sinica. Vol. XII, № 2. May, 1993. p. 137-146.

- Санчиров В. П. О Происхождении этнонима торгут и народа, носившего это название // Монголо-бурятские этнонимы: cб. ст. — Улан-Удэ: БНЦ СО РАН, 1996. C. 31—50. - in Russian

- Ovtchinnikova O., Druzina E., Galushkin S., Spitsyn V., Ovtchinnikov I. An Azian-specific 9-bp deletion in region V of mitochondrial DNA is found in Europe // Medizinische Genetic. 9 Tahrestagung der Gesellschaft für Humangenetik, 1997, p. 85.

- Galushkin S.K., Spitsyn V.A., Crawford M.H. Genetic Structure of Mongolic-speaking Kalmyks // Human Biology, December 2001, v.73, no. 6, pp. 823–834.

- Хойт С.К. Генетическая структура европейских ойратских групп по локусам ABO, RH, HP, TF, GC, ACP1, PGM1, ESD, GLO1, SOD-A // Проблемы этнической истории и культуры тюрко-монгольских народов. Сборник научных трудов. Вып. I. Элиста: КИГИ РАН, 2009. с. 146-183. - in Russian

- [hamagmongol.narod.ru/library/khoyt_2008_r.htm Хойт С.К. Антропологические характеристики калмыков по данным исследователей XVIII-XIX вв. // Вестник Прикаспия: археология, история, этнография. № 1. Элиста: Изд-во КГУ, 2008. с. 220-243.]

- Хойт С.К. Кереиты в этногенезе народов Евразии: историография проблемы. Элиста: Изд-во КГУ, 2008. – 82 с. ISBN 978-5-91458-044-2 (Khoyt S.K. Kereits in enthnogenesis of peoples of Eurasia: historiography of the problem. Elista: Kalmyk State University Press, 2008. – 82 p. (in Russian))

- [hamagmongol.narod.ru/library/khoyt_2012_r.htm Хойт С.К. Калмыки в работах антропологов первой половины XX вв. // Вестник Прикаспия: археология, история, этнография. № 3, 2012. с. 215-245.]

- Boris Malyarchuk, Miroslava Derenko, Galina Denisova, Sanj Khoyt, Marcin Wozniak, Tomasz Grzybowski and Ilya Zakharov Y-chromosome diversity in the Kalmyks at theethnical and tribal levels // Journal of Human Genetics (2013), 1–8.

- National Census 2010

- Perdue 2009, p. 295.

- DeFrancis, John. In the Footsteps of Genghis Khan. University of Hawaii Press, 1993.

- Turkistan: 2 (5 ed.). Sampson Low, Marston, Searle &Rivington. 1876.

- Turkistan: 2 (5 ed.). Sampson Low, Marston, Searle &Rivington. 1876. p. 181.

- Schuyler, Eugene (1876). Turkistan: Notes of a Journey in Russian Turkistan, Khokand, Bukhara and Kuldja, Volume 2 (2 ed.). S. Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington. p. 181.

- Schuyler, Eugene (1876). Turkestan: Notes of a Journey in Russian Turkistan, Khorand, Bukhara, and Kuldja (4 ed.). Sampson Low. p. 181.

- Michel Hoàng, Ingrid Cranfield-Genghis Khan, p.323