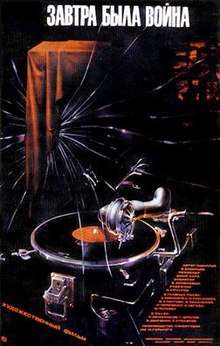

Tomorrow Was the War

Tomorrow Was the War (Russian: Завтра была война, romanized: Zavtra byla voyna) is a 1987 Soviet drama film directed by Yuri Kara based on the eponymous novella by Boris Vasilyev.[1][2] The film was Kara's thesis at VGIK.[3]

| Tomorrow Was the War | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Yuri Kara |

| Produced by | Vitaly Golubev |

| Written by | Boris Vasilyev |

| Starring | Sergei Nikonenko Nina Ruslanova Vera Alentova Natalya Negoda |

| Music by | Sergei Slonimsky |

| Cinematography | Vadim Semyonovykh |

| Edited by | Alla Myakotina |

Production company | |

Release date |

|

Running time | 85 min. |

| Country | USSR |

| Language | Russian |

Synopsis

The film is set in 1940. Life in class 9b begins as usual. Children on the threshold of adult life get to know themselves, learn to love and understand each other. The story is centered around Iskra Polyakova – class prefect, daughter of principled party worker comrade Polyakova. Iskra is a self-assured Komsomolka who was brought up by a fanatically devoted to the party mother. Her ideals are inviolable and the concepts seem clear-cut and correct to her. Gathered at the birthday party of one of her classmates, Iskra listens to the verses of Sergei Yesenin which are read by her friend Vika, daughter of the town's famous aircraft designer Leonid Lyuberetsky. Iskra likes Yesenin's poetry, but she considers him an alien to Soviet culture "tavern singer." This was how she was taught. Vika gives her classmate the book and explains to Iskra, that Yesenin was not a 'decadent' poet and that feelings are an integral part of life. Several days pass. Iskra meets the father of Vika, begins a deeper understanding of some things, asks her mother and herself questions, tries to understand the concepts of justice, duty and happiness.

The school's existence takes its natural course: the children study, fall in love with each other. Even Iskra accepts courting of former classmate Sasha Stameskin whom Lyuberetsky hired at his factory. But everything changes suddenly. One evening, the teens learn that designer Lyuberetskiy was arrested on suspicion of subversive activities against the Soviet Union.

Iskra decides to support her girlfriend, despite her mother's warning of impending repression. The school head teacher Valentina Andronovna calls Lyuberetskaya into the office and says that tomorrow at the school line she should publicly renounce her father and call him an "enemy of the people." Vika refuses. After that, "Valendra" invites Polyakova to office and asks her to convene a meeting, having expelled Luberetskaya from the Komsomol with disgrace. Iskra declares to the head teacher that she will never do this and faints from over-excitement. The school principal takes the girl into the medical office and praises her for the manifestation of humanity.

Having learned about the heroism of her girlfriend and devotion of her compatriots, Vika Lyuberetskaya invites the children to a picnic. Outside the city she confesses her love to classmate Jaurès Landys, and the students kiss each other for the first time. In the morning Vika does not come to the Komsomol meeting. When the head teacher sends classmate Zina for her, she returns in a semiconscious state and informs the class that "Vika is in the morgue." Iskra is summoned by the investigator and is informed that Lyuberetskaya committed suicide, leaving two suicide notes, including one addressed personally to Polyakova. Vika's classmates learn that there is no one to bury the girl and decide to take care of the burial themselves.

Mother of Iskra asks not to read speeches and hold a memorial service; she calls Lyuberetskaya's suicide an act of a "namby-pamby". However, she goes against the will of the mother and impressed by the school principal speech at the cemetery, reads Yesenin's verses over the grave of her friend. Luberetsky’s daughter’s funeral is watched from a distance by Sasha Stameskin. He is worried about his future career and does not dare to visit the funeral of the public enemy's daughter in the open. Iskra's verse reading is discovered by her mother and she organizes a scandal with an attempt to use physical force. However, Iskra says that if she once again raises her hand to her, she will leave forever, despite love. Vika's funeral also has consequences for the principal; he is fired.

One more month passes by. The shock of Vika Lyuberetskaya's death gradually subsides. After a festive demonstration in honor of November 7, class of 9b visits the former director. In his apartment, the children learn that the Civil War hero is removed from the party.

Finals time. Students write an essay, and it is known at this time that Leonid Sergeevich Lyuberetskiy is acquitted and allowed to go home. The class darts off and is in a hurry to support the designer in his grief. The teens find Lyuberetsky among rickety frames and scattered chairs in his apartment who still remembers the NKVD search. "What a tough year", - says the father of Vika. In an outburst of feelings Zina throws her arms around him and tells him that it is a sad year only because it is a leap one and that the next in 1941 will be very happy. The class freezes. In the scene Red Army soldiers marching through the streets accompanied by the song The Sacred War are visible. The epilogue sounds.

Cast

- Sergei Nikonenko as Nikolai Grigorievich Romakhin, headmaster

- Nina Ruslanova as Comrade Polyakov, Iskra's mother

- Vera Alentova as Valendra (Valentina Andronovna), head teacher

- Irina Cherichenko as Iskra Polyakova

- Natalya Negoda as Zina Kovalenko

- Julia Tarkhova as Vika Lyuberetskaya

- Vladimir Zamansky as Leonid Sergeevich Lyuberetsky, Vika's father

- Rodion Ovchinnikov as Jaurès Landys

- Gennady Frolov as Sasha Stameskin

- Vladislav Demchenko as Pasha Ostapchuk

- Sergei Stolyarov as Artyom Schaefer

Production

In his youth, director Yuri Kara read the book "Tomorrow Was the War" by Boris Vasilyev and wanted to make a film based on it. He knew that many directors attempted to get permission to adapt the novel from Goskino but all were rejected. But Kara was granted the right to film the adaptation by his teacher Sergei Gerasimov at VGIK. As the film was his dissertation, it was not taken seriously enough to be under censorship. But after the movie was finished, there was difficulty as the whole Goskino was against the film, but Armen Medvedev from the state committee defended the picture and it was released.[4]

Initially the picture was planned as a short, a three-reeler. But the Gorky Film Studio became interested in the film and shooting continued which caused it to become a full-fledged feature film. It was shot without sound or finished text, this is visible in many scenes where the dubbing does not fully match the mouth movements.[4] As it was a student project, many actors played for free in the film.[5]

The film's soundtrack includes, besides the classical compositions by Antonio Vivaldi original music from the 1930s. The war, which is about to take place, is indicated with the song The Sacred War. The film is dedicated to Sergei Gerasimov who died before the film was released. It was Natalia Negoda's screen debut, she plays the student Zina in the film. Her mother in the film Yelena Molchenko actually was the same age as Negoda. The parts of the film in which the students were outside of the party's immediate constraints, including scenes in Lyuberetsky's apartment and the students' excursion the day before Vika's suicide, were shot in color, the rest in black and white.

Awards

- The film was awarded the Dovzhenko Gold Medal for "Best military-patriotic film", it received top prizes at international film festivals in Spain, France, Germany and Poland.

- The main prize "Grand Amber" at the 1987 International Film Festival in Koszalin (Poland).[6]

- Special Jury Prize at the 1987 International Filmfestival Mannheim-Heidelberg (Germany).[7]

- Grand Prix "Golden Ear" at the 1987 International Film Festival in Valladolid (Spain).

- Grand Prix at the 1988 "Film Convention in Dunkirk" (France).

- Gold medal named after Alexander Dovzhenko in 1988 awarded to director Yuri Kara, screenwriter Boris Vasilyev, actors Sergey Nikonenko Nina Ruslanova.

- 1987 Nika Award was awarded to actress Nina Ruslanova for the films "Tomorrow Was the War", "Sign of Misfortune", Brief Encounters.[8]

References

- "Завтра была война. Х/ф". Russia-K.

- "Завтра была война". Encyclopedia of Native Cinema.

- "Завтра была война". VokrugTV.

- ""Завтра была война"". Argumenty i Fakty.

- "Завтра была война: 5 знаменитых фильмов Юрия Кары". Vechernyaya Moskva.

- "15. KOSZALIŃSKI FESTIWAL DEBIUTÓW FIMOWYCH". KOSZALIŃSKI FESTIWAL DEBIUTÓW FIMOWYCH.

- "Archiv". International Filmfestival Mannheim-Heidelberg. Archived from the original on 2017-02-24.

- "Лауреаты Национальной кинематографической премии «НИКА» за 1987 год". Nika Award.