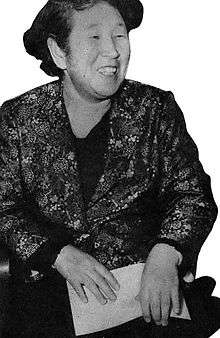

Tomi Kōra

Tomi Kōra (高良 とみ Kōra Tomi, July 1, 1896 – January 17, 1993)[1] was a Japanese psychologist, peace activist, and politician. She published under the name Tomiko Kōra (高良 とみ Kōra Tomiko).

Early life and education

Kōra was born Tomi Wada[lower-alpha 1] on July 1, 1896 in Toyama Prefecture.[2][3][1] She graduated from the Japan Women's University in 1917.[2][1] While a student, she attended the funeral of Tsuriko Haraguchi, held at the university. Haraguchi was a psychologist and the first Japanese woman to obtain a PhD; Kōra was reportedly inspired by Haraguchi to continue her advanced studies in psychology.[1]

Like Haraguchi, she attended Columbia University, earning her Master's degree in 1920 and her Ph.D. in 1922.[2] At Columbia, she collaborated with Curt Richter to conduct her experiments on the effects of hunger.[3][1] Kōra's doctoral dissertation, completed under the supervision of Edward L. Thorndike, was titled An Experimental Study of Hunger in its Relation to Activity.[3][1][4] She was the second Japanese woman to obtain a Ph.D. in psychology, after Haraguchi.[3]

Career

After returning to Japan, Kōra worked as an assistant in a clinical psychiatry laboratory and taught at Kyushu Imperial University. She was promoted to associate professor, but was met with resistance because she was unmarried at the time.[1] She resigned from the institution in 1927 and took a post at Japan Women's University, where she became a professor.[1]

Kōra was a member of the Japanese Christian Women's Peace Movement, and travelled to China. There, in January 1932, she met the Chinese writers Lu Xun and Xu Guangping at a bookstore owned by the Japanese Kanzō Uchiyama; shortly after, Lu Xun wrote a poem for her.[5]

Kōra was elected as a Councillor in the 1947 Japanese House of Councillors election, as a member of the Democratic Party. She switched to the Ryokufūkai party in 1949, and served in the House of Councillors for 12 years.[4]

In April 1952, Kōra attended the International Economic Conference in Moscow.[4][6] Per a request from the US embassy, the Japanese Foreign Ministry had refused to issue passports to those who wished to travel to the Soviet Union; Kōra got around this restriction by travelling to Moscow through Paris, Copenhagen, and Helsinki. They met with vice-minister of the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Trade Lei Rei-min and were invited to Beijing. At the time, the Japanese government did not recognize the legitimacy of the PRC government.[7] That May, she visited Beijing as a member of the House of Councillors Special Committee for the Repatriation of Overseas Japanese. The visit was a diplomatic breakthrough, resulting in the first PRC–Japan private-sector trade agreement (signed June 1, 1952[7]) and the resumption of the repatriation of Japanese left in China following the end of World War II.[8] Both praise and opposition greeted the trade agreement from Japanese legislators.[9]

Kōra spent four days as a guest at the Women's International Zionist Organization in Israel in April 1960.[10]

Personal life

In 1929, Kōra married psychiatrist Takehisa Kōra[lower-alpha 2].[1][11] They had three daughters, including the poet Rumiko Kōra[lower-alpha 3].[11] Kōra was a practising Quaker.[5]

Notes

- 和田 とみ Wada Tomi

- 高良 武久 Kōra Takehisa

- 高良 留美子 Kōra Rumiko

References

- McVeigh, Brian J. (12 January 2017). The history of Japanese psychology : global perspectives, 1875-1950. London. ISBN 978-1-4742-8308-3. OCLC 958497577.

- "Japanese Psychologists: K-L". A Brief Guide to the History of Japanese Psychology. Oklahoma State Psychology Museum & Resource Center. 2004. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- Takasuna, Miki (2012). "History of Psychology in Japan". In Rieber, Robert W. (ed.). Encyclopedia of the History of Psychological Theories. New York, NY: Springer. pp. 570–581. ISBN 978-1-4419-0425-6.

- Ōizumi, Hiroshi, 1940-; 大泉溥, 1940- (2003). Nihon shinri gakusha jiten. 大泉溥, 1940-. Tōkyō: Kuresu Shuppan. ISBN 4-87733-171-9. OCLC 52857261.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Kowallis, Jon Eugene von. (1996). The lyrical Lu Xun : a study of his classical-style verse. Lu, Xun, 1881-1936. Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 0-8248-1511-4. OCLC 32394571.

- "JAPANESE WOMAN AT MOSCOW PARLEY; Diet Member Went Without Permission While 24 Men Meekly Stayed at Home". New York Times. 8 April 1952. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- Shimizu, Sayuri, 1961- (2001). Creating people of plenty : the United States and Japan's economic alternatives, 1950-1960. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. ISBN 0-87338-706-6. OCLC 45375185.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Itoh, Mayumi, 1954- (2010). Japanese war orphans in Manchuria : forgotten victims of World War II (1st ed.). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-10636-9. OCLC 688186455.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Shimizu, Sayuri, 1961- (2001). Creating people of plenty : the United States and Japan's economic alternatives, 1950-1960. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. ISBN 0-87338-706-6. OCLC 45375185.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Oron, Yitzhak, ed. (1960). Middle East Record Volume 1, 1960. London: George Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- 小村大樹. "歴史が眠る多磨霊園 - 高良とみ". Retrieved 22 November 2019.