Tomb of Caecilia Metella

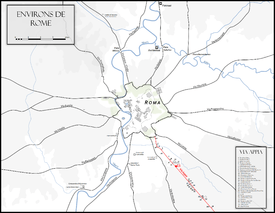

The Tomb of Caecilia Metella (Italian: Mausoleo di Cecilia Metella) is a mausoleum located just outside Rome at the three mile marker of the Via Appia. It was built during the 1st century BC to honor Caecilia Metella who was the daughter of Quintus Caecilius Metellus Creticus, a consul in 69 BC, and wife of Marcus Licinius Crassus who served under Julius Caesar and was the son of the famous triumvir Marcus Crassus.[1]

| Mausoleo di Cecilia Metella | |

Tomb of Caecilia Metella | |

| Coordinates | 41°51′7.8″N 12°31′15.26″E |

|---|---|

| Location | Via Appia, Rome |

| Type | Roman Mausoleum |

| Material | Concrete, Travertine |

| Completion date | 1st Century BC |

| |

The Tomb of Caecilia is one of the most well known and well preserved monuments along the Via Appia and a popular tourist site. In 2013, the museum circuit of the Baths of Caracalla, Villa of the Quintilii, and the Tomb of Caecilia Metella was the twenty-second most visited site in Italy, with 245,613 visitors and a total gross income of €883,344.[2]

Description

Located on top of a hill along the Via Appia, the Tomb of Caecilia Metella consists of a cylindrical drum, or rotunda, atop a square podium with the Caetani Castle (Castrum) attached at the rear. The square podium stands at 8.3 meters tall with the cylindrical drum standing at 12 m. The monument in totality stands at a height of 21.7 meters tall. The diameter of the circular drum is 29.5 m, equivalent to 100 Roman feet.

On the outside of the monument, an inscription can be seen reading "CAECILIAE |Q·CRETICI·F | METELLAE·CRASSI[3]" indicating to whom this tomb was dedicated. Further up the monument, decorations can be seen depicting festoons and bucrania, heads of bulls, which were the inspiration for the area being named Capo Di Bove, meaning head of the bovine. At the top of the monument, medieval battlements can be seen from the time when the tomb was used as a fortress.

At the rear, the Caetani Castle is attached to the tomb. The castle originally was three levels: ground level, first level, and second level. It is unknown what the second level was used for but the first floor was used for the elite gentlemen as evidenced by fireplaces and refined goods.[4] The castle is now used to display various decorations from the monument.

Mausoleum

Structure

The foundation of the Tomb of Caecilia Metella rests partially on tuff rock and partially on lava rock. The lava rock is part of ancient lava flow from the Alban Hills that covered the area 260,000 years ago.[5]

The core of the podium was cast in several layers of concrete, ranging from .7 to .85 m thick. The thickness of each layer corresponds with the height of the travertine facing blocks that surrounded the podium as the travertine was used as a frame in order to help the concrete layers form.[6]

The rotunda was built in this same fashion, travertine blocks on the outermost section with cement poured in the middle to give the concrete some structure and then covered in Travertine revetment, most of which has been stripped away. While the walls of the tower are 24 ft thick, comparatively the adjoining castle of the Gaetani was made of a thin wall of tufa.

Originally the top of the monument would have been a cone shaped earthen mound as conical shapes were common with Roman rotundas but the earthen mound has long been replaced by medieval battlements.

The Roman concrete was made up of semi-liquid mortar and aggregate, which consisted of broken pieces of stone or bricks. The aggregate was made up of rather large pieces of stone (about the size of a fist) compared to modern cement which is finely ground to create a smooth, flat surface. Mortar and concrete were alternated in the construction as the semi-liquid mortar would bind the stone pieces together. The mortar used at this tomb utilized the lava rock beneath the monument as a substitute for sand in the concrete. The lava rock worked as well as sand and was more abundant versus the difficult to find sand.

Interior

The interior of the Tomb of Caecilia Metella can be separated into 4 sections: the cella, the upper and lower corridors, and the west compartment. The most important being the cella which was used for funerary purposes and for "housing" the dead.

The cella is a tall, circular shaft rising all the way through the center of both the podium and the rotunda. The cella is about 6.6 m in diameter at the bottom but tapers as it rises to a 5.6 m diameter at the top. The top features an oculus allowing for light. Throughout the cella, there are over 143 cut outs, divided into 12 rows of 10-14, in the walls of the cella that were used as putlog holes in the creation of the monument.

The upper corridors is believed to be the main entrance to the cella.

Exterior

The upper section of the rotunda is decorated quite minimally with a marble frieze of bucrania, oxen heads, and garlands. Beneath the frieze is the famous inscription "CAECILIAE |Q·CRETICI·F | METELLAE·CRASSI" meaning "To Caecilia Metella, daughter of Quintus Creticus, [and wife] of Crassus".

Decorations were very popular on funerary altars and votive offerings and the most famous example are identified in the frieze of carved ox skulls and festoons on the inside of the fence.[7] Three types of bull heads can be distinguished: complete bovine head, skull of bull but still covered with skin, and a full skeletal skull. The inclusion of the naked skull is indicative of the termination of use of the complete bull skull and the skull with skin occurred around 30 BC and the inclusion of the use of particular bull heads allows for an approximate date to be made, as bull heads seen on dated monuments can be compared.

The bull heads and garlands indicate and verify the timing of the creation of the monument. During the time period, the Roman decoration of bull heads was shifting and thus the representation of particular bull heads approximate the date.

Sarcophagus

Today, there is a marble sarcophagus located in Palazzo Farnese that is purportedly from the Tomb of Caecilia Metella. According to literary sources, it was found in the cella and had been there since before the construction of the Caetani Castle. However, there is no definitive evidence to verify the sarcophagus as the sarcophagus of Caecilia Metella and many historians believe the sarcophagus does not belong to the monument and had been found in the surrounding area of the mausoleum rather than inside it.

Recently, the sarcophagus was the object of a detailed study and the author of this study dates sarcophagus between AD 180 and 190. Further evidence suggesting this to not be the sarcophagus of Caecilia Metella is at the time of Caecilia Metella's death, cremation was the typical burial custom and a funerary urn is expected rather than a sarcophagus.[6] In addition, records from 1697 of the Farnese Collection state the sarcophagus was registered without a specified provenience indicating even at the time, historians were unsure of the relationship between the sarcophagus and the tomb.

Castrum

Between 1302 and 1303, the Caetani, or Gaetani, family aided by Pope Boniface VIII bought the estate of Capo di Bove, which was all the land surrounding and including the Tomb of Caecilia Metella, and built a fortified camp, or castrum, next to the tomb replacing a preceding 11th century building. [8]

The castrum's construction included the building of stables, houses, warehouses, the church of St. Nicholas, and the palace of the Caetani as well as adding the medieval battlements to the top of the tomb thus transforming the tomb into a defensive tower. Sadly, the remnants of the Caetani only include the Church of St. Nicholas, parts of the Caetani Palace, and the medieval battlements.

The Caetani used this fort to control the traffic on the road and to collect exorbitant tolls. In the fourteenth century the castle was passed to the Savelli, and to the Orsini who held it until 1435, after which it became the property of the Roman Senate.[9] According to Gerding, the monument was abandoned in 1485.[6]

Over the centuries, the two monuments endured numerous attempts of destruction in order to repurpose their materials. However, the two monuments protected one another from destruction. During the Renaissance, the monuments were saved as they were valued for the castrum while during Romanticism, the tomb, with its charm, allowed the survival of the castrum.[4]

Gallery

.jpg) Exterior

Exterior.jpg) Inscription

Inscription- Inside the cella

- Caetani Castle

.jpg) Caetani Castle

Caetani Castle- Rear of Tomb and Castle

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tomb of Caecilia Metella. |

References

- Coarelli, Filippo (2008) Rome and Environs: An Archæological Guide. pg 393. ISBN 0520079612. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- Ministry of Heritage and Culture, museum visitors and revenue

- CIL VI, 1274

- Archaeological Study of Castrum Caetani

- Adams, William Henry Davenport (1872) Temples, Tombs, and Monuments of Ancient Greece and Rome: A Description and a History of Some of the Most Remarkable Memorials of Classical Architecture pg. 194. ISBN 1295187698

- Gerding, Henrik (2002) The Tomb of Caecilia Metella:Tumulus, Tropaeum, and Thymele. ISBN 9162853422

- Queen of Roads: Appian Way

- History of Castrum Caetani

- History of Castrum Caetani

Bibliography

- Coarelli, Filippo (2008) Rome and Environs: An Archæological Guide. ISBN 0520079612, ISBN 9780520079618

- Gerding, Henrik (2002) The Tomb of Caecilia Metella:Tumulus, Tropaeum, and Thymele. ISBN 9162853422, ISBN 9789162853426

- Maddrell, Avril & Sidaway, James D (2012) Deathscapes: Spaces for Death, Dying, Mourning and Remembrance pg. 227-230. ISBN 1409488837, ISBN 9781409488835

- Vandercasteele, Maurits (2004), "Two Presumed Drafts for Engravings Belonging to Antonio Lafrery's "Speculum Romanae Magnificeni", Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte: 427–434, doi:10.2307/20474260, JSTOR 20474260