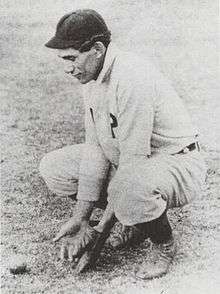

Charlie Grant

Charles Grant Jr. (August 31, 1874 – July 9, 1932)[5] was an American second baseman in Negro league baseball. Grant nearly crossed the baseball color line decades before Jackie Robinson when Major League Baseball manager John McGraw attempted to pass him off as a Native American named "Tokohama".[6]

| Charlie Grant | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Second baseman | |||

| Born: August 31, 1874 Cincinnati | |||

| Died: July 9, 1932 (aged 57) Cincinnati | |||

| |||

| debut | |||

| 1896, for the Page Fence Giants | |||

| Last appearance | |||

| 1916, for the Cincinnati Stars | |||

| Teams | |||

| |||

Background

Grant was born in Cincinnati, the son of an African American horse trainer, Charles Grant, and mother, Mary.[7][8] A good fielder, Grant was of "medium height" and weighed approximately 160 pounds and hit right-handed.[7][9]

When star second basemen Sol White and Bud Fowler left the Page Fence Giants after just one season, Charlie Grant replaced them in 1896.[10] [11] Grant and Page Fence defeated White's new team, the Cuban X-Giants, ten games to five to win an 1896 championship series played in various southern Michigan, Indiana and Ohio towns.[12] [13] Page Fence disbanded in 1899 and Grant moved with most of the players to the Columbia Giants of Chicago.[14] He also captained the Columbia Giants for at least part of one season.[6]

Tokohama

After spending 1900 with Columbia, Grant was working as a bellhop at the Eastman Hotel in Hot Springs, Arkansas in March 1901. John McGraw and the new American League's Baltimore Orioles began training that season in Hot Springs and staying at the Eastland. McGraw saw Grant playing baseball with his co-workers around the hotel and recognized that Grant had a level of talent suitable for the major leagues.[15] McGraw decided to disguise the light-skinned, straight-haired Grant as a Cherokee and gave him the name Charlie Tokohama, anecdotally after noticing a creek named "Tokohama" on a map in the hotel.[7][14][15]

McGraw's scheme began unravelling when the team travelled to Chicago, where Grant had played for the previous few years. To celebrate Grant's return, his African American friends staged a conspicuous ceremony, including a flower bouquet.[16] Chicago White Sox President Charles Comiskey soon objected to "Tokohama" and affirmed that he was actually Grant.[17] Grant maintained his disguise, claiming that his father was white and that his mother was Cherokee and living in Lawrence, Kansas.[18] McGraw initially persisted but later claimed that "Tokohama" was inexperienced, especially on defense, and left him off his Opening Day roster. Grant returned to the Columbia Giants and never played in the major leagues.[8]

Later career and accidental death

Grant played for the Cuban X-Giants in 1903.[7] After Sol White's Philadelphia Giants were defeated in the 1903 "colored championship", White overhauled the team including hiring Charlie Grant to replace Frank Grant (no relation).[10][19] In 1905, Charlie Grant, White, shortstop Grant Johnson and third baseman Bill Monroe were considered one of the best infields in Negro League history.[20] Grant and the Giants won the championship in 1906. He also played for the Fe club in 1906.[5] He later played for the Lincoln Giants, Quaker Giants, New York Black Sox and Cincinnati Stars, last playing in 1916.[7]

Grant's 1918 military registration card lists his home address as 802 Blair Avenue in Cincinnati, Ohio, and his birth date as August 31, 1877 – three years later than his accepted birth date. His mother is listed as a contact at the same address and his employment as "janitor" at the same address as his home, through a company called "Thomas Emery and Sons."[21]

In July 1932, Grant was killed while sitting in front of a Cincinnati apartment building where he worked as a janitor. A passing automobile hit him after its tire exploded.[7] Grant was buried in Spring Grove Cemetery and his grave is a short distance from fellow second baseman, Baseball Hall of Fame member Miller Huggins.[8]

Notes

- "Giants Win" Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette, Cedar Rapids, IA, Friday, April 23, 1897, Page 5, Column 1

- "The Columbia Giants of Chicago" Indianapolis Freeman, Indianapolis, IN, Saturday, March 24, 1900, Page 7, Column 1

- "Cuban X-Giants are Champions" The Patriot, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Saturday, September 19, 1903, Page 7, Column 1

- "Pottstown and Philadelphia Giants" Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Tuesday Morning, June 21, 1904, Page 10, Column 5

- "Charlie Grant Negro League Statistics & History". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- "Grant Ordered to Baltimore" Fort Wayne Morning Journal-Gazette, Fort Wayne, IN, Sunday, May 19, 1901, Page 5, Column 5

- Riley, p. 330.

- Peterson, p. 56.

- Peterson, p. 54 gives a description of Grant (as "Tokohama") from Sporting Life.

- White, Malloy, p. xxxv.

- The Page Fence Giants, A History of Black Baseball's Pioneering Champions, Mitch Lutzke, p. 235

- White, p. 37, Malloy, p. xxxv.

- Lutzke, p. 241

- Bak, p. 49.

- Peterson, p. 54.

- White, p. 78.

- Peterson, p. 55.

- Peterson, pp. 55–56.

- White, Malloy, p. xl.

- White, Malloy, p. xxxviii.

- "United States, World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918," index and images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/K6F3-FC5 : accessed 26 Feb 2013), Charles Grant

References

- Bak, Richard (1995). Turkey Stearnes and the Detroit Stars. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-2582-3.

- Lutzke, Mitch, (2018). The Page Fence Giants, A History of Black Baseball's Pioneering Champions. McFarland & Company, Inc. Jefferson, North Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4766-7165-9

- Peterson, Robert (1970). Only the Ball was White. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507637-0.

- Riley, James A. (1994). "Grant, Charles (Charlie, Chief Tokahoma)". The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues. Carroll & Graf. pp. 330. ISBN 0-7867-0959-6.

- (Riley.) Charlie Grant, Personal profiles at Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. – identical to Riley (confirmed 2010-04-13)

- White, Sol (1996) [1907]. Sol White's History of Colored Baseball with Other Documents on the Early Black Game, 1886–1936. introduction by Jerry Malloy. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-9783-1.

External links

- Cuban League statistics and player information from Seamheads.com, or Baseball-Reference (Negro leagues)