Tin can telephone

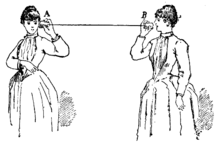

A tin can telephone is a type of acoustic (non-electrical) speech-transmitting device made up of two tin cans, paper cups or similarly shaped items attached to either end of a taut string or wire.

It is a particular case of mechanical telephony, where sound (i.e., vibrations in the air) is converted into vibrations along liquid or solid medium. These vibrations are transmitted along the medium and then reconverted back to sound. In the case of tin can telephone the medium is a string.

History

Before the invention of the electromagnetic telephone, there were mechanical acoustic devices for transmitting spoken words and music over a distance greater than that of normal speech. The very earliest mechanical telephones were based on sound transmission through pipes or other physical media, and among the very earliest experiments were those conducted by the British physicist and polymath Robert Hooke from 1664 to 1685.[1][2] From 1664 to 1665 Hooke experimented with sound transmission through a taut distended wire.[3] An acoustic string phone is attributed to him as early as 1667.[4]

The highly similar acoustic tin can telephone, or 'lover's phone', has also been known for centuries. It connects two diaphragms with a taut string or wire, which transmits sound by mechanical vibrations from one to the other along the wire (and not by a modulated electric current). The classic example is the children's toy made by connecting the bottoms of two paper cups, metal cans, or plastic bottles with tautly held string.[1][5]

For a short period of time acoustic telephones were marketed commercially as a niche competitor to the electrical telephone, as they preceded the latter's invention and didn't fall within the scope of its patent protection. When Alexander Graham Bell's telephone patent expired and dozens of new phone companies flooded the marketplace, acoustic telephone manufacturers could not compete commercially and quickly went out of business. Their maximum range was very limited, but hundreds of technical innovations (resulting in about 300 patents) increased their range to approximately a half mile (800 m) or more under ideal conditions.[5] An example of one such company was Lemuel Mellett’s 'Pulsion Telephone Supply Company' of Massachusetts, which designed its version in 1888 and deployed it on railroad right-of-ways, purportedly with a range of 3 miles (4.8 km).[2][6]

In the centuries before tin cans and paper cups became commonplace, other cups were used and the device was sometimes called the "lovers' telephone". During the 20th century, it came into common use in preschools and elementary schools to teach children about sound vibration.

Operation

When the string is pulled taut and someone speaks into one of the cans, its bottom acts as a diaphragm, converting the sound waves into longitudinal mechanical vibrations which vary the tension of the string. These variations in tension set up longitudinal waves in the string which travel to the second can, causing its bottom to vibrate in a similar manner as the first can, thus recreating the sound, which is heard by the second person.

The signal can be directed around corners with at least two methods: The first method can be implemented by creating a loop in the string which is then twisted and anchored to another object.[7] Another method makes use of an extra can positioned on the apex of the corner; the string is threaded through the base of the can so as to avoid coming into contact with the object around which the signal is to be directed. [8]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tin can telephones. |

- History of the telephone

- Sound powered telephone

- Speaking tube

References

- McVeigh, Daniel P. An Early History of the Telephone: 1664–1866: Robert Hooke's Acoustic Experiments and Acoustic Inventions Archived 2013-06-18 at the Wayback Machine, Columbia University website. Retrieved January 15, 2013. This work in turn cites:

- Richard Waller and edited by R.T. Gunther. "The Postthumous Works of Robert Hooke, M.D., S.R.S. 1705. Reprinted in R.T. Gunther's "Early Science In Oxford", Vol. 6, p. 185, 25

- Grigonis, Richard. A Telephone in 1665?, TMCNet Technews website, December 29, 2008.

- Preface to Micrographia (1665) «I have, by the help of a distended wire, propagated the sound to a very considerable distance in an instant». Micrographia - Extracts From The Preface

- Giles, Arthur (editor). County Directory of Scotland (for 1901-1904): Twelfth Issue: Telephone (Scottish Post Office Directories), Edinburgh: R. Grant & Son, 1902, p. 28.

- Jacobs, Bill. Acoustic Telephones, TelefoonMuseum.com website. Retrieved January 15, 2013. This article in turn cites:

- Kolger, Jon. "Mechanical or String Telephones", ATCA Newsletter, June 1986; and

- "Lancaster, Pennsylvania Agricultural Almanac for the Year 1879: How to Construct a Farmer's Telephone", John Bater's Sons.; and

- "Telephone Experiences of Harry J. Curl as told by him to E. T. Mahood, During the summer of 1933 at Kansas City, Missouri: First Telephone Experience."

- "The Pulsion Telephone", New Zealand: Hawke's Bay Herald, Vol. XXV, Iss. 8583, January 30, 1890, p. 3.

- Benson, Robert (12 March 2018) [Created in 2014]. "How do you get can phones to go around corners?". Can Phones and Corners. Google Sites. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- NPASS2 String Telephones Archived 2012-10-14 at the Wayback Machine, “Corner Busters” photos taken 7 October 2012.