Ticket of leave

A ticket of leave was a document of parole issued to convicts who had shown they could now be trusted with some freedoms. Originally the ticket was issued in Britain and later adapted by the United States, Canada, and Ireland.

Jurisdictions

Australia

The ticket of leave system was first introduced by Governor Philip Gidley King in 1801. Its principal aim was to reduce the burden on the fledgling colonial government of providing food from the government's limited stores to the convicts who were being transported from the United Kingdom to Australia and its colonies of New South Wales and Tasmania. Convicts who seemed able to support themselves were awarded a ticket of leave. Before too long, tickets began to be given as a reward for good behaviour, which permitted the holders to seek employment within a specified district, but not leave it without the permission of the government or the district's resident magistrate. Each change of employer or district was recorded on the ticket.[1]

Originally the ticket of leave was given without any relation to the period of the sentence a convict had already served. Some "gentlemen convicts" were issued with tickets on their arrival in the colony. Starting in 1811, the need to first officiate some time in servitude was established, and in 1821 Governor Brisbane introduced regulations specifying the lengths of sentences that had to be served before a convict could be considered for a ticket: four years for a seven-year sentence, six to eight years for a 14-year sentence, and 10 to 12 years for those with a life sentence. Once the full original sentence had been served, a "certificate of freedom" would be issued upon application. If a life sentence had been given, then the convict could get a ticket to leave and/or conditional or full pardon.[2][3]

Ticket-of-leave holders were permitted to marry, or to bring their families from Britain, and to acquire property, but they were not permitted to carry firearms or board a ship. Convicts who observed the conditions of the ticket of leave until the completion of one half of their sentence were entitled to a conditional pardon, which removed all restrictions except a ban on leaving the colony. Convicts who did not observe the conditions of their ticket could be arrested without warrant, tried without recourse to the Supreme Court, and would forfeit their property. The ticket of leave had to be renewed annually, and those with one had to attend muster and church services.

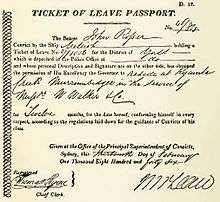

The ticket itself was a highly detailed document, listing the place and year the convict was tried, the name of the ship in which he or she was transported, and the length of the sentence. There was also a complete physical description of the convict, along with year of birth, former occupation and "native place".

A ticket had two components: The "ticket proper" was issued to the person named, and it was mandatory for the person to carry that document on their person at all times. The second component was the "butt", which was the official copy and was kept on file by the Government. Tickets proper are now quite rare as they were in constant use by the holder. The butts are still retained in archival records and are available for researchers.

According to Alexander Maconochie, tickets of leave could be suspended in summary fashion for the most "trifling irregularities," and a "very large proportion" of ticket-of-leave holders were returned to government work as a result.[4]

British military

In the Second World War, the "ticket of leave" was a colloquial name given to the papers allowing a soldier to take leave from active service.[5]

Canada

On August 11, 1899, An Act to Provide for the Conditional Liberation of Convicts - the Ticket of Leave Act - was enacted by the Canadian Parliament.

The Canadian Ticket of Leave Act was based almost word for word on the British legislation. There was no reference in the text to the purpose of conditional release, though ticket of leave was generally understood to be a form of pardon.

In the beginning, the Governor General granted paroles on the advice of Cabinet as a whole. The act was later amended so that the power to advise the Governor General was limited to the Minister of Justice. This was a significant departure from traditional practice in the use of executive clemency; it was an attempt to separate parole decisions from politics. Even so, because conditional release was still in the hands of an elected minister, public opinion would still have a strong, and sometimes questionable, influence on policy.

In the early 20th century, Canada was sparsely settled. Keeping track of men on tickets of leave was difficult and the authorities relied on parolees to report every month to the police. This had its drawbacks, and when the Salvation Army offered to take over parole supervision in some places, the Department of Justice was glad to accept. Salvation Army officers acted as Dominion Parole Officers until the position was abolished in 1931.

On March 7, 1939, Bill C-34 was passed, revising the Penitentiary Act and creating an administrative board of three.

Ireland

Walter Crofton administered the Irish ticket of leave system.

See also

- Certificate of Freedom

- The Ticket-of-Leave Man

References

- "Bottomley: Parole in Transition: A Comparative Study of Origins, Developments, and Prospects for the 1990s". scholar.google.com. Retrieved 11 May 2008.

- "Convicts and the British colonies in Australia". australia.gov.au. Australian Government. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- Alexander B. Smith; Louis Berlin (1988). Treating the criminal offender. Springer. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-306-42885-2. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- Doherty, Fiona (2013). "Indeterminate Sentencing Returns: The Invention of Supervised Release". N.Y.U. L. Rev. 88 (958).

- Smith, Richard (2004). Jamaican volunteers in the First World War : race, masculinity and the development of national consciousness (1. publ. ed.). Manchester Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6985-7.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Ticket-of-leave. |