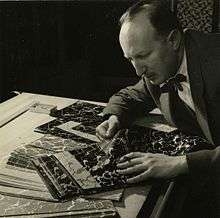

Tibor Reich

Tibor Reich ATI, FSIA, FRSA (1 October 1916 – 3 February 1996) was one of Britain's pioneering post-war textile designers. His company, Tibor Ltd., made its name by providing cutting-edge designs that were popular with both the public and featured in key post-war projects including The Festival of Britain, Concorde, Royal Yacht Britannia, Coventry Cathedral, Clarence House and the QE2. Reich was awarded a Design Council Award in 1957 and a Textile Institute Medal in 1973.[1]

Tibor Reich | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Tibor Reich October 1, 1916 Budapest, Hungary |

| Died | February 3, 1996 (aged 79) |

| Nationality | British-Hungarian |

| Alma mater | University of Leeds |

| Occupation | Textile Designer |

| Spouse(s) | Freda Caplan |

Early Life/University

Born in Budapest in 1916, Tibor Reich was from a family of wealthy Jewish textile industrialists. Encouraged by his father, he drew prodigiously from a young age. In 1933 he left Budapest to study textile design and architecture in Vienna,[2] where he was influenced by the legacy of the Wiener Werkstätte and the Bauhaus. With the rise of Nazism in 1937 Reich emigrated to Britain to study textiles at Leeds University.[3]

Then the world's leading centre for textile technology, science and woven design Reich achieved a first-class result in the City and Guilds Institute examination in Woolen and Worsted Weaving. It was here that he learnt to experiment and was awarded a Diploma in Textile Industries in September 1941, following the submission of a thesis entitled ‘The Economical Production of Novelty Fabrics’.[4] After graduating from Leeds, Reich went to work for Tootals of Bolton, but left after a year.

Tibor Ltd

In 1946 Reich moved to Stratford upon Avon and set up Tibor Ltd in a nineteenth-century mill at Clifford Chambers. From his studio he established a small weaving unit, where he set to work designing and manufacturing speciality fabrics. His early weaves were snapped up for dress couture including by the prestigious Edward Molyneux, who used them for their 1946 United States export collection because of their originality and colouration.

In the same year 1947, he submitted one of his first hand woven furnishing fabric designs for selection by H.R.H. Princess Elizabeth, now H.M Queen Elizabeth. It was chosen as a wedding gift presented by the International Wool Secretariat.[5]

In the space of two years Reich was already employing over 50 staff and by 1948 had won a $100,000 order from Hambro House of Design in New York.[6] By 1951 he was awarded a Certificate of Merit by the American Institute of Decorators.

Deep Textured Weaves

Up until the early 1950s British textiles, in particular furnishing fabrics, showed little consideration to colour, texture and modern pattern, with most relying on traditional motifs, and woven in a simple process. Inspired by the Bauhaus and his pre-war training, Reich's Deep Textures were woven in such a way as to give a third dimension to the surface pattern. This new technique brought a ‘pattern out of texture’ and opened up the possibility of exploring and freeing colour from two dimensional surfaces.[7]

Michael Farr stated in 1954 that Reich had started a ‘new phase in the development of British modern design for woven textiles.’[8] As Sir Terrance Conran stated in 1957 “Tibor Reich is internationally known for his woven and printed textiles. The texture and weave of the cloth to be printed on are especially considered in his designs’[9]

Reich designed ‘Deep Textures’ for The Festival of Britain including The Southbank Festival Pavilions, Fairway Café, The Press Room, and The Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford upon Avon, where he draped and upholstered the entire building. Major furniture manufacturers upholstered using Tibor fabrics including Ernest Race, Gordon Russell, Robin Day, Howard Keith, G Plan and Ercol.[10]

In 1952 Reich had his first solo major show named ‘Deep Textures with Rayon’ at The Rayon Industry Design Centre designed by Hulme Chadwick RDI. In 1954 Liberty, in conjunction with The Council of Industrial Design, held a solo show of Reich's work named ‘Adventure with Colour’, opened by Sir Percy Thomas. It would later travel around the UK.

Reich was commissioned to drape many of the key post-war projects of the 1950s. In 1954 Sir Hugh Casson and Sir Misha Black chose Tibor fabrics to drape The Royal Yacht Britannia and Time and Life Building. Other projects in the 1950s included London Airport (Heathrow), Arts Council UK, Berkeley and Washington Hotel, Renfrew Airport, Coventry Cathedral and the 1958 British Pavilion at the World's Fair, Brussels. In 1953 ICI commissioned Tibor to weave and design a tapestry for their coronation celebrations (also shown at the 10th Milan Triennial)[11] and in 1958 Sanderson commissioned five tapestries to celebrate their 100th anniversary.

Tibor fabrics were also commissioned by BOAC, Conair, Hawker Siddeley planes and Cunard ships including RMS Empress of England, RMS Queen Elizabeth, RMS Ivernia and RMS Saxonia. He also acted as a designer for Quayle and Tranter,[12] Wilton, Denby, Stockwell, and Bigelow and Sanford, USA. Tibor also collaborated with Courtaulds on seating fabrics for Vauxhall motor cars.

1960s

One of the commercial highlights for Tibor Ltd in the 1960s was a commission to design the first sets of upholstery and curtain fabrics for the Anglo-French Concorde. Five Jacquard upholstery cloths in natural and gold were used as curtaining fabrics along with two carpet designs.[13]

During the 1960s Tibor fabrics were also on the QE2 and in embassies, Royal Palaces, hotels, Nos. 10 and 11 Downing Street, Board of Trade Building, Windsor Castle, Shakespeare Centre and for The Hotel Piccadilly in Manchester over six miles of fabric was produced by Tibor.[14]

During the 1960s Reich was commissioned to create works for major British institutions. These often took the form of richly coloured glowing tapestries and included designs for Coventry Cathedral, Manchester University, a 100-metre tapestry for The Board of Trade Westminster and the Academy Cinema. Tibor had showrooms in Old Burlington Street and Sloane Street and were stocked globally from the US to Japan. By the 1960s Tibor Ltd was employing over 60 design staff and was the largest privately owned Textile Design studio in the UK.[15] Tibor fabrics were produced in over eight mills throughout the country including Gregs Quarry Bank Mill, who part owned Tibor Ltd.

Fotextur – Council of Industrial Design Award 1957

During the 1950s Reich, fed up with using a brush to imitate nature and feeling this method was repetitive set to work on experimenting with patterns deriving from photography. Whilst looking at a snapshot of his wife he noticed the light and shade patterns on a section of an old stone wall. In his dark room he set about distilling the pattern from the wall, henceforth starting the development of his new patented process ‘Fotextur.’ Through this process a pattern was produced by taking a photograph of a natural object or feature, making positive and negative prints from the photograph, and then re-arranging to make a design.

In 1957 the Fotextur fabric ‘Flamingo’ was awarded a Council of Industrial Design award presented by Prince Philip in its inaugural year.[16] Michael Farr wrote a seven-page article in Design calling it ‘revolutionary’ and observed that the Fotextur method although taking nature as its principal source, stepped beyond visual expressions that could be classified simply as floral or geometric. Indeed, he stated ‘Mr Reich has discovered a new way of seeing nature’ and in doing so created his own distinctive handwriting.[17] Pathe news also featured a four-minute news reel on Fotextur.[18]

Fotextur was used on textiles, carpets, tiles, bags and pottery.[19]

Colotomic – Design Centre 1960

Launched at The Design Centre, Haymarket ‘Colotomic’ was an evolution of the Fotextur process. It featured a print named ‘Atomic’ that derived pattern from one of the first photographs ever taken of an atom-splitting experiment.[20]

It was however also unique for its use of colour. In 1953 Reich had trademarked a pre-pantone idea of systematic colour charting called Collingo. ‘Atomic’ came in fourteen colourways each colourway contained four tones of a single colour.[21] There were three principle colour groups and each tone within each group of colour both contrasted and worked together. The range was intended to allow the consumer to mix colourways in one setting. In a three-page article for Design magazine Stephen Garrett stated ‘By careful selection of the colourways, it should be possible to get the exact overall colour effect that is wanted.’ [22]

Shakespeare

Reich and Shakespeare crossed paths many times. His first brush was after moving to Stratford upon Avon and Clifford Mill in 1952 when he was chosen as part of Stratford's contribution to the Festival of Britain, to drape and upholster the new Shakespeare Memorial Theatre (RSC) He named the fabrics after Shakespearean characters: Cymbeline, Oberon, Macbeth, Prospero.[23]

In 1964, in celebration of Shakespeare's 400th Anniversary, Reich was commissioned by the Shakespeare Council to design and print a commemorative tapestry. His selection as the designer best suited to interpret the Shakespearean idiom in terms of modern fabrics also made him responsible for designing and weaving the fabrics and tapestries for the new Shakespeare Centre, which was opened by H.R.H. Duke of Edinburgh. His most famous tapestry was ‘Age of Kings’ and is now seen as an iconic 60s print and featured in the V&A collection.[24]

Pottery – Denby Tigo-Ware

Finding there was a noticeable lack of pottery which could co-ordinate with his Deep Textured fabric, in 1952 he designed his own studio pottery range called Tigo-Ware. Originally crafted from the back shed at their 600-year-old cottage its demand soon outgrew their facilities and was by 1954 produced in volume by Denby. The Council of Industrial Design included over fourteen of the Tigo pieces in their design review, which was an illustrated record of British designs of the highest standard.

As a range it had a unique style that was essentially sophisticated, highlighted by flashes of gentle humour.[25] Pieces ranged from utilitarian to sculptural. The expressing curving lines were enhanced by the tactile quality of black, lightly textured, matt-glazed surfaces. This was scratched using the scraffito technique to expose the white earthenware body beneath.[26] Tigo-Ware bridged tradition with modernity. Pieces were often inspired by Hungarian folk art, yet re-interpreted in a modern 1950s style.[27]

Tibor House

Having trained in architecture in pre-war Vienna by 1956 Reich set to work on his own house. Drawing on Bauhaus ideas of functionality and movement the house was used as both laboratory and show-room where textiles, furniture, floor and wall coverings, paint-work and lighting were thoroughly tested and shown from a practical as well as an aesthetic point of view.[28]

The 1950s house confronts experimental glass with timber, innovative concrete, steel and atomic structures, indoor gardens and sliding doors. It also has one of Britain's most famous free standing mosaic fireplaces of the 1950s dubbed the ‘flaming onion,’[29] cabins for his children's bedrooms and refrigerated filing cabinets for the kitchen (inspired by the Frankfurt Kitchen). A lot of these ideas were later taken up by industry. Comments about the house in 1957 included “The first imaginative use of the English open fire in a modern home. Architects can now work on from here,” Dr Jacob Bronowski, in stark contrast to Sir Norman Hartnell who stated “Monstrous without beauty. Any view through that meanly constructed window would be more pleasing than the hideous room behind”[30]

Model Car Museum

Set up for his two sons, the museum was opened by Lord Montagu of Beaulieu in 1963.[31] By the mid-1970s Tiatsa was the largest model car collection in Europe. It is now on display at Coventry Transport Museum and totals over 30,000 models.[32] In 1984 the entire collection was showcased on BBC's Blue Peter programme.

Later life

Tibor Reich died in 1996 aged 79 in Stratford Upon Avon. He was survived by his wife Freda Caplan, a concert pianist who was a pupil of Frederic Lamond[33] and his four children.

Museums

Tibor Reich's works are included in the archives of:

- V&A, London

- ULITA, Leeds

- Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester

- Geffrye Museum, London

- Powerhouse Museum, Sydney

- National Museum of Stockholm

- VADS, University of Brighton Design Archives

- Shakespeare Centre, Stratford upon Avon

References

- "Medals and Awards". The Textile Institute. Retrieved March 13, 2018.

- Jackson, Lesley (2002). Twentieth Century Pattern Design. Princeton Architectural Press. p. 105. ISBN 9781568987125.

- Woodham, Jonathan. A Dictionary of Modern Design. Oxford University Press.

- Hann, M.A.; K. Powers (2009). "Tibor Reich – A Textile Designer Working in Stratford" (PDF). Textile History. 40 (2): 212–228. doi:10.1179/004049609x12504376351506.

- "Princess Elizabeth Chooses New Fabric". St Petersburg Times. 1947.

- "Europeans Design Gay New Fabrics". Miami Daily News. 1950.

- Reich, Tibor (1959). "Responsibility of the Designer To-Day". Journal of the Textile Institute. 50 (7): 330–6. doi:10.1080/19447015908664268.

- Farr, Michael (1954). "Design Magazine".

- Conran, Terrance (1957). Printed Textile Design. The Studio Limited, London. pp. 48–49.

- "Resource for Visual Arts".

- "Private Venture in Milan". Art and Industry. 1954.

- "Design Council Slide Collection".

- "Assembling the Concorde". Editoriale Domus. March 10, 2012. Retrieved March 13, 2018.

- Margot, Coatts (February 1996). "Obituary:Tibor Reich". The Independent.

- Golding, Robert (1973). "If you want something you believe in - you have to do it yourself". The Birmingham Post.

- "V&A Archive, Winner of CoID Design of the Year award, 1957".

- Farr, Michael (April 1957). "Fotexur, Pattern making based on photographs". Design, The Council of Industrial Design.

- "Nature Designs In Fabric". British Pathe News 1957.

- "Design Council Archive". VADs.

- Jackson, Lesley (2010). From Atoms to Patterns: Crystal Structure Designs from the 1951 Festival of Britain: The Story of the Festival Pattern Group. Richard Dennis Publications. p. 31. ISBN 9780955374111.

- "X-Ray Marks the Spot: William Astbury and the Birth of Molecular Biology at Leeds".

- Garrett, Stephen (1960). "Design Magazine. Council of Industrial Design".

- Pringle, Marian. "I would I were a weaver. Fabric Designs of Tibor Reich at the Shakespeare Centre". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "V&A Collection". V&A.

- Hopwood, Irene, Gordon (1997). Denby Pottery 1809-1997: Dynasties and Designers.

- Mclaren, Graham (1997). Ceramics of the 1950s. Shire Publications Ltd. p. 27. ISBN 9780747803362.

- Wykes-Joyce, Max (1958). 7000 years of pottery and porcelain. Philosophical Library.

- "A House on Show". House and Garden. 1957.

- "English House on Two Levels". The Sydney Morning Herald. 1958.

- "Mr Reich's Flaming Onion Starts a Heated Argument". Sunday Dispatch. 1958.

- Tiatsa Model Car Museum Opening Speeches by Lord Montagu and Tibor Reich in 1963.

- M. Pearce, Susan (2002-01-01). The Collector's Voice: Critical Readings in the Practice of Collecting, Volume 4. Ashgate. ISBN 9781859284209.

- "Pupil of Lamond". The Glasgow Herald. 1942.