Tibetan partridge

The Tibetan partridge (Perdix hodgsoniae) is a gamebird in the pheasant family Phasianidae of the order Galliformes. They are found widely across the Tibetan Plateau and have some variations in plumage across populations. They forage on the ground in the sparsely vegetated high altitude regions, moving in pairs during the summer and in larger groups during the non-breeding season. Neither males nor females have spurs on their legs.

| Tibetan partridge | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Galliformes |

| Family: | Phasianidae |

| Genus: | Perdix |

| Species: | P. hodgsoniae |

| Binomial name | |

| Perdix hodgsoniae (Hodgson, 1857) | |

Description

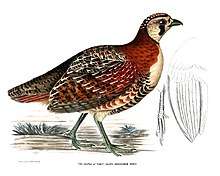

Somewhat different in appearance from the other Perdix species such as the grey and Daurian partridges this 28–31 cm long partridge has the brown back, blackish belly patch and chestnut flanks of its relatives, but has a striking black and white face pattern, which contrasts with the rufous collar.

The forehead, broad supercilium, face and throat are white. A broad black stripe runs down the face from below the eyes and it has a broad chestnut hind neck collar. The upper parts are buff, barred with rufous and black. The other tail-feathers are chestnut, tipped with white. The lower plumage is pale buff closely barred with black, with broad chestnut bars on the flanks. The male has a black belly patch which is barred in the female. The female is otherwise similar to the male but duller, and the juvenile is a featureless buff-brown, lacking the distinctive facial and underpart markings of the adult. Sexes are similar in size.[2][3]

Tibetan partridge (Ladakh, India). |

Taxonomy and systematics

The scientific name of Sacfa hodgsoniae was given by Brian Houghton Hodgson to commemorate his first wife, Anne Scott.[4] The original genus proposed by Hodgson was based on the Tibetan name for it, Sakpha.[5] There are 16 tail feathers while most other Perdix species have 18. Neither males nor females have spurs on their legs.[6] Phylogenetic studies place the species as basal within the genus.[7] There are three subspecies differing mainly in the plumage becoming darker further east:[8][9]

- hodgsoniae, described by Hodgson, is found from eastern Tibet, through western Nepal, to northeast India (Assam). The nuchal collar is broad and dark chestnut. The black of the cheek extends below throat as a collar.

- sifanica, described by Przhevalsky, is found in west central China up to eastern Tibet and central and south Sichuan. Like the nominate form but the black of the cheek is restricted.

- caraganae, described by Meinertzhagen, is found in northwest India to eastern Tibet. The nuchal collar is narrow and a pale yellowish chestnut.

Distribution and status

This partridge breeds on the Tibetan plateau in Tibet itself, Northern Pakistan via Kashmir into northwestern Indian, northern parts of Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan, and western China. The Tibetan partridge appears to be secure in its extensive and often inaccessible range on the Tibetan Plateau.[1]

Behaviour and ecology

It is found on mountain slopes and high meadows with some Rhododendron bushes, dwarf juniper or other scrubs for cover, typically between 3,600-4,250 m (11,800–14,000 ft). Despite its striking appearance, the head and breast pattern provide good cryptic camouflage in its rocky habitat. It is a non-migratory terrestrial species, but moves to lower altitude desert plains in winter, and may ascend to the snowline in summer. This is a seed-eating species, but the young in particular take insects as an essential protein supply.

The Tibetan partridge forms flocks of 10-15 birds outside the breeding season, which tend to run rather than fly. When disturbed sufficiently, like most of the game birds it flies a short distance on rounded wings, the flock scattering noisily in all directions before gliding downhill to regroup.

In summer beginning around mid-March the birds pair up to form monogamous bonds with the pair staying close together. The nest site varies from bare rocky plateau with few stunted bushes and tufts of coarse grass to small thorny scrub or even standing crops. Nests tend to be close to paths. The nest is a grass-lined depression, sometimes devoid of any lining. The typical clutch is 8-10 brownish-buff eggs and is laid during May to June. The male assists in looking after the young.[4][9][10][11]

The usual call heard mainly in the mornings is a rattling scherrrrreck- scherrrrreck , and the flight call is a shrill chee chee chee.[12]

In Lhasa these partridges appeared to prefer stream belts with scrub and in winter they preferred south-facing slopes and open fields. They sometimes rest under bushes in the day and roost under dense scrub at higher elevation slopes in the night. They form pairs during the breeding season and after the breeding season form larger groups.[13]

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Perdix hodgsoniae". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oates, EW (1898). A manual of the Game birds of India. Part 1. A J Combridge, Bombay. pp. 191–194.

- Rasmussen PC & JC Anderton (2005). Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide. Volume 2. Smithsonian Institution & Lynx Edicions. p. 121.

- Hume, AO (1890). The nests and eggs of Indian Birds. Volume 3 (2nd ed.). R H Porter, London. pp. 438–439.

- Hodgson, B.H. (1856). "On a new Perdicine bird from Tibet". Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal: 165–166.

- Blanford WT (1898). Fauna of British India. Birds. Volume 4. Taylor and Francis, London. pp. 142–143.

- Xin-kang Bao; Nai-fa Liu; Jiang-yong Qu; Xiao-li Wang; Bei An; Long-ying Wen; Sen Song (2010). "The phylogenetic position and speciation dynamics of the genus Perdix (Phasianidae, Galliformes)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 56 (2): 840–847. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.03.038. PMID 20363341.

- Hartert, E (1921–22). Die Vögel der paläarktischen Fauna. Volume 3. Friedlander and Sohn, Berlin. pp. 1936–1938.

- Baker, ECS (1928). Fauna of British India. Birds. Volume 5 (2nd ed.). Taylor and Francis, London. pp. 423–426.

- Lu X, Gong G, Ren C (2003). "Reproductive Ecology of Tibetan Partridge Perdix hodgsoniae in Lhasa Mountains, Tibet". Journal of the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology. 34 (2): 270–278. doi:10.3312/jyio1952.34.270.

- Hume AO & CHT Marshall (1880). The Game birds of India, Burmah and Ceylon. Self published. pp. 65–68.

- Ali, S & SD Ripley (1980). Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan. Volume 2 (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press, New Delhi. pp. 35–36.

- Lu X, Ciren S (2002). "Habitat Selection and Flock Size of Tibetan Partridge Perdix hodgsoniae during Autumn-Winter". Journal of the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology. 33 (2): 168–175. doi:10.3312/jyio1952.33.168.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Perdix hodgsoniae. |