Thomas Pinckney (American Civil War)

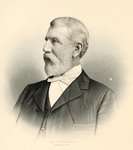

Captain Thomas Pinckney (August 13, 1828 – November 14, 1915) was a Southern rice planter and Confederate veteran of the American Civil War[1]. He was the grandson of Major General Thomas Pinckney and one of the Immortal Six Hundred.

Captain Thomas Pinckney | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | August 13, 1828 Charleston, SC |

| Died | November 14, 1915 (aged 87) |

| Buried | Magnolia Cemetery |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1861-1865 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Battles/wars | Battle of Haw's Shop |

Early life

Pinckney was the fourth child and second son born to father Charles Cotesworth Pinckney (1789-1865) and mother Phoebe Caroline Elliot Pinckney (1792-1864) . He grew up in the family house in Charleston SC and on the family rice plantations on the South Santee River Delta, which included Fairfield Plantation, El Dorado Plantation, Echaw Grove, Fannymead Plantation and Moreland Plantation. He frequently also spent time in the upcountry of South Carolina and western North Carolina to escape the summer heat and disease of the South Carolina Lowcountry. He attended the University of Virginia but left to study medicine back in Charleston and then New York.[2]

Civil War

Pinckney helped form and then lead the St James Mounted Riflemen whose purpose was to defend the various plantations on the Santee River delta from Northern raids. He further used his land at Echaw Plantation to build Battery Warren to protect a Confederate railroad bridge over the Santee. Over time he and his men were re-organized under the command of then-Major Arthur Middleton Manigualt in McClellanville and then, later, under General M. C. Butler they were sent to Virginia. At the Battle of Haw's Shop Pinckney was captured. As a prisoner-of-war, he was nearly starved to death and held in the line of fire at Morris Island by Union soldiers in retaliation for the treatment of Union soldiers held by the Confederacy. He and the others so treated became known in the Confederacy as the Immortal Six Hundred for their refusal to take an oath of allegiance to the United States. Eventually, Pinckney was exchanged for Union soldiers and paroled.[3]

Later Life

After the war, Pinckney returned to El Dorado and the other family plantations on the Santee to inspect their condition and, hopefully, return them to productive work growing rice. The former slaves, known as freedmen, were mostly still at the houses as they had no other residence or place to go. After months of negotiations, many agreed to contracts under which they would provide labor in return for living on the land and receiving a share of whatever crops were harvested. However, flooding and poor weather combined with low rice prices prevented rice from returning to its former profitability and in 1886 Pinckney finally gave up agriculture and so ended nearly 150 years of family rice growing on the Santee.

Pinckney married twice. First on April 20th, 1870 to Miss Mary Stewart of Richmond Virginia and then, after Mary's death, to Camilla Scott also of Virginia on July 12th, 1892. He had one surviving child from his first marriage, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney (1875 - 1934) , and a daughter from his second marriage, the Southern writer Josephine Pinckney. He lived variously with his in-laws the Stewarts at their family house Brookhill and back in Charleston. [4] He died in Charleston and is buried in Magnolia Cemetery.

References

- L., Bellows, Barbara (2018-03-14). Two Charlestonians at war : the Civil War odysseys of a Lowcountry aristocrat and a black abolitionist. Baton Rouge. ISBN 9780807169094. OCLC 1000051356.

- Thomas Pinckney Proof Sheets, Accession 11112, Special Collections Department, University of Virginia Library

- Confederate Veteran. S.A. Cunningham. 1916.

- "The Brook Hill Timeline | The Brook Hill Family". brook-hill.net. Retrieved 2018-04-15.