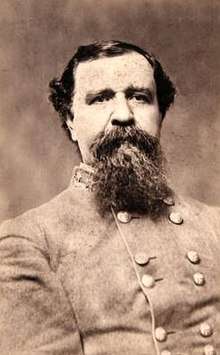

Thomas H. Taylor

Thomas Hart Taylor (July 31, 1825 – April 12, 1901) was a Confederate States Army colonel, brigade commander, provost marshal and last Confederate post commander at Mobile, Alabama during the American Civil War. His appointment as a brigadier general was refused by the Confederate Senate after Confederate President Jefferson Davis failed to nominate Taylor, apparently following Davis's appointment of Taylor to the rank. Nonetheless, Taylor's name is frequently found on lists and in sketches of Confederate generals. He was often referred to as a general both during the Civil War and the years following it. Before the Civil War, Taylor served as a first lieutenant in the 3rd Kentucky Volunteer Infantry Regiment during the Mexican–American War. After that war, he was a cattle driver, farmer and lawyer. After the Civil War, he was engaged in business in Mobile, Alabama for five years, and after returning to Kentucky, was a Deputy U.S. Marshal for five years and was chief of police at Louisville, Kentucky for eleven years.

Thomas H. Taylor | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 31, 1825 Frankfort, Kentucky |

| Died | April 12, 1901 (aged 75) Louisville, Kentucky |

| Buried | Frankfort, Kentucky |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1846–1848 (USA) 1861–1865 (CSA) |

| Rank | Brigadier General (CSA) (unconfirmed) |

| Battles/wars | Mexican–American War American Civil War |

| Other work | Chief of police, Louisville, Kentucky |

Early life

Thomas H. Taylor was born July 31, 1825 at Frankfort, Kentucky.[1] He was the son of Edmund Taylor, second cousin once removed of President and Major General Zachary Taylor, and his second wife, a Miss Hart.[2] Taylor attended Kenyon College in Ohio and graduated from Centre College in Kentucky in 1843.[1][3][4]

During the Mexican–American War, Taylor served in the 3rd Kentucky Infantry Regiment, at first as a private, and then as a first lieutenant.[1][3][5] Taylor was a cattle driver, farmer and lawyer before the war.[1][3][4]

Taylor was married three times.[6] In 1844, he married Sarah Elizabeth Blandford.[6] They had one child, Edmund Haynes Taylor, before her death in 1858.[6] In 1864, he married Sarah A. Moreland of Mobile, Alabama, who died some time before 1878.[6] In 1878, he married Eliza Adair Monroe.[6] They had four children, Mary Louise, John Adair Monroe, Thomas Hart Jr. and Adair Monroe.[6]

American Civil War service

Thomas H. Taylor began his Confederate Army Civil War service as a captain of cavalry in the Army of the Confederate States of America, the Regular Army of the Confederacy.[1][3][4] According to one source, on July 3, 1861, he became lieutenant colonel of the Confederate 1st Kentucky Infantry Regiment.[1] Other sources indicate that the 1st Kentucky Infantry was not formed until August 7, 1861.[7] In early July 1861, Taylor was either a member of the personal staff of Confederate President Jefferson Davis or at least a special messenger on his behalf.[7][8][9] On July 6, 1861, Taylor took dispatches from Jefferson Davis for President Abraham Lincoln.[7][8][9] These dispatches insisted that the crew of the privateer Savannah be treated as prisoners of war and exchanged and threatened retaliation against Union Army prisoners if the crew were hanged as pirates.[7][9]

After proceeding to Manassas Junction, Virginia by railroad, on July 8, 1861, with an escort of about 12 men from Fairfax, Virginia, Taylor set out under a flag of truce toward the Union Army headquarters of Major General Irvin McDowell at Arlington, Virginia, presumably to ultimately present the dispatches to President Lincoln.[7][9][10] About seven miles from Arlington, Taylor was met by Union Colonel, soon to be Brigadier General, Andrew Porter, a comrade from the Mexican–American War and First Lieutenant, later Brigadier General, William W. Averell.[7][9][10][11] After some personal conversation between Taylor and Porter, a Union cavalry escort took Taylor to Arlington, where they found McDowell was out.[7] Taylor was taken to the office of U.S. Army General-in-Chief, Brevet Lieutenant General Winfield Scott in Washington when Scott learned of his mission and that McDowell was not present to receive him.[9][10] Scott sent the dispatches to President Lincoln.[9][10] Scott served wine and champagne while they waited for a reply.[9][10] Due to the late hour, after 10:00 p.m., Lincoln sent no reply.[9][10] Scott sent Taylor back to Major General Irvin McDowell for more hospitality and to stay the night, promising that he would send a reply from Lincoln promptly.[10] After breakfast and with a stack of northern newspapers, Taylor and his party were escorted back to the Confederate lines.[7][10] Lincoln never responded to Davis's messages.[9][10] However, he did not enforce the stated policy of hanging privateers as pirates.

On August 7, 1861, General Joseph E. Johnston combined two Kentucky battalions into the 1st Kentucky Infantry Regiment. Lieutenant Colonel Taylor was ordered to take command.[7] On September 28, 1861, the regiment skirmished with small Union Army units as the Confederates evacuated Mason's Hill and Munson's Hill, about four miles from Alexandria, Virginia.[7] Taylor was promoted to colonel on October 14, 1861.[1][3][7] On December 20, 1861, the regiment fought at the Battle of Dranesville as part of a large foraging party under the overall command of Brigadier General J.E.B. Stuart.[7] Taylor became separated from his men while moving down his line and had to extricate himself from behind enemy lines after nightfall.[7][12]

Taylor's regiment was assigned to Brigade 5, Division 1 of the Army of East Tennessee in March 1862.[1][13] The 1st Kentucky Infantry was a 12-month regiment which was mustered out of the Confederate States Army in the summer of 1862.[3] Taylor was assigned to brigade command in the Department of East Tennessee by Major General E. Kirby Smith.[1][4] This division served at Cumberland Gap and in Kentucky.[3][4]

Thomas H. Taylor was appointed brigadier general on November 4, 1862 but the Confederate Senate refused the appointment when Confederate President Jefferson Davis failed to nominate Taylor.[1][3][14]

After commanding a brigade in Major General Carter L. Stevenson's division of the Department of Mississippi and East Louisiana from July 1862 through April 1863, Taylor became provost marshal[3] and inspector general for the Army of Mississippi under Lieutenant General John Pemberton at Vicksburg, Mississippi.[1][5][15] He was in command of an attack on Donaldsonville, Louisiana on June 27, 1863[16] or June 28, 1863,[17] which was repulsed in part by gunboats on the Mississippi River.[16][17]

Taylor was captured at the fall of Vicksburg to Union forces commanded by Major General Ulysses S. Grant on July 4, 1863[1][4][15] He was paroled, went to Montgomery, Alabama and was later exchanged.[5][15]

After his exchange, Taylor had brief service at Mobile, Alabama and then was given command of the District of Mississippi and East Louisiana in the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana from March 5, 1864 to April 28, 1864.[1][15][18] Taylor was delayed by Union Major General William T. Sherman's capture of Meridian, Mississippi after the Battle of Meridian from February 14 to February 20, 1864.[15] Taylor took command on March 30, 1864.[15] He had a difficult time due to his small number of troops and civilian discontent as well as Union raids.[15] Taylor was relieved on April 28, 1864 by Colonel John S. Scott, who had lived in East Louisiana, and reported to department headquarters at Demopolis, Alabama.[15]

On June 24, 1864, Taylor became provost marshal of the Department of Alabama and East Mississippi under Lieutenant General Stephen D. Lee at Meridian.[1][4][15] From November 1864 until the end of the war, Taylor was in command of the post at Mobile, Alabama.[1][4][5][15] In this capacity, he commanded only some reserve and local defense troops, charged more with maintaining order than defending the city, which he was compelled to evacuate with Confederate troops from local forts on April 11, 1865.[5][15] According to some sources, no record of his parole has been found,[1] but at least one source says Taylor was paroled on May 5, 1865 with troops at Jackson, Mississippi where he acted as parole commissioner for Confederate troops in that area under orders from Lieutenant General Richard Taylor.[15]

Aftermath

After the Civil War, Taylor moved to Alabama where he engaged in business at Mobile until 1870.[3] He returned to Kentucky and served for five years as deputy U.S. Marshal.[3] Taylor was chief of police of Louisville, Kentucky from 1881 to 1892.[1][3][4] Even though he had no experience as an engineer, he was superintendent of the Louisville and Portland Canal between February 1886 and 1889 when he was replaced due to a change in administration.[15] Thomas Hart Taylor died at Louisville, Kentucky on April 12, 1901 of typhoid fever.[1][3][4][19] Taylor was buried at State Cemetery, Frankfort, Kentucky.[1][3]

Notes

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. Civil War High Commands. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3. p. 612.

- Espy, William R.Oysterville: Roads to Grandpa's Village. New York: C.N. Potter: Distributed by Crown Publishers, 1977. ISBN 978-0-517-52196-0. Retrieved February 3, 2012. p. 229.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 0-8071-0823-5. pp. 300–301.

- Schultz, Fred L. "Taylor, Thomas Hart" in Historical Times Illustrated History of the Civil War, edited by Patricia L. Faust. New York: Harper & Row, 1986. ISBN 978-0-06-273116-6. p. 744.

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts On File, 1988. ISBN 0-8160-1055-2. p. 643.

- Allardice, Bruce S. and Lawrence L. Hewitt. Kentuckians in Gray: Confederate Generals and Field Officers of the Bluegrass State. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8131-2475-9. Retrieved February 1, 2012. p. 263.

- Allardice, 2008. p. 259.

- Beatie, Russel Harrison. The Army of the Potomac: Birth of command, November 1860-September 1861. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-306-81141-8. p. 211.

- Robinson, William Morrison. 'The Confederate privateers'. Columbia, SC: Univ. of South Carolina Press, 1990. Reprint of 1928 edition. 978-0-87249-691-0. Retrieved February 2, 2012. pp. 134–135.

- Beatie, 2002, p. 212.

- Beattie, 2002, p. 212 agrees with the editors of the Jefferson Davis Papers, Baton Rouge and London, 1971–1995, that the officer was Thomas H. Taylor, not John G. Taylor as stated by the editor of Averell's memoirs, which are incomplete. Moreover, Davis himself wrote that Colonel Thomas Taylor was the messenger. Davis, Jefferson. 'The rise and fall of the Confederate government, Volume 2', New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1881. OCLC 547724. Retrieved February 3, 2012. p. 584. Scharf thus also errs by stating that the messenger was Colonel Richard Taylor. Scharf, John Thomas. History of the Confederate States Navy From Its Organization to the Surrender of Its Last Vessel. New York: Rogers & Sherwood, 1887. OCLC 317589712. Retrieved February 1, 2011. p.75.

- Stuart, J.E.B. Engagement at Dranesville, Virginia in Confederate War Journal, Volume 2. New York; Lexington, KY: War Journal Pub. Co., "The printery", 1893-1895. OCLC 602549967. Retrieved February 3, 2012. pp. 55–58.

- Warner, 1959, p. 300 and Sifakis, 1988, p. 643 say that the regiment saw some service in the Peninsula Campaign. This seems to contradict Eicher's statement of the date the regiment was assigned to duty in Tennessee.

- Boatner, Mark Mayo, III. The Civil War Dictionary. New York: McKay, 1988. ISBN 0-8129-1726-X. First published New York, McKay, 1959. p. 828.

- Allardice, 2008, p. 262

- Fredriksen, John C. 'Civil War Almanac'. New York: Facts on File, 2007. ISBN 978-0-8160-6459-5. p. 317.

- Long, E. B. The Civil War Day by Day: An Almanac, 1861–1865. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1971. OCLC 68283123. pp. 372–373.

- Eicher gives an end date of April 5 but in view of Allardice's more specific information, including Taylor's arrival only on March 30, Allardice's end date is given in the text.

- Welsh, Jack D. 'Medical Histories of Confederate Generals' Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-87338-505-5. Retrieved February 1, 2012. pp. 211–212.

References

- Allardice, Bruce S. and Lawrence L. Hewitt. 'Kentuckians in gray: Confederate generals and field officers of the Bluegrass State'. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8131-2475-9. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- Beatie, Russel Harrison. 'The Army of the Potomac: Birth of command, November 1860-September 1861'. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-306-81141-8.

- Boatner, Mark Mayo, III. The Civil War Dictionary. New York: McKay, 1988. ISBN 978-0-8129-1726-0. First published 1959 by McKay.

- Davis, Jefferson. 'The rise and fall of the Confederate government, Volume 2', New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1881. OCLC 547724. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Espy, William R.'Oysterville: Roads to Grandpa's Village'. New York: C.N. Potter : Distributed by Crown Publishers, 1977. ISBN 978-0-517-52196-0. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- Long, E. B. The Civil War Day by Day: An Almanac, 1861–1865. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1971. OCLC 68283123.

- Robinson, William Morrison. 'The Confederate privateers'. Columbia, SC: Univ. of South Carolina Press, 1990. Reprint of 1928 edition. 978-0-87249-691-0. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- Schultz, Fred L. "Taylor, Thomas Hart" in Historical Times Illustrated History of the Civil War, edited by Patricia L. Faust. New York: Harper & Row, 1986. ISBN 978-0-06-273116-6.

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts On File, 1988. ISBN 978-0-8160-1055-4.

- Stuart, J.E.B. Engagement at Dranesville, Virginia in Confederate War Journal, Volume 2. New York; Lexington, KY: War Journal Pub. Co., "The printery", 1893-1895. OCLC 602549967. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.

- Welsh, Jack D. 'Medical Histories of Confederate Generals' Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-87338-505-5. Retrieved February 1, 2012.