Thirty Years' Peace

The Thirty Years' Peace was a treaty signed between the ancient Greek city-states of Athens and Sparta in 446/445 BCE. The treaty brought an end to the conflict commonly known as the First Peloponnesian War, which had been raging since c. 460 BCE.

Background

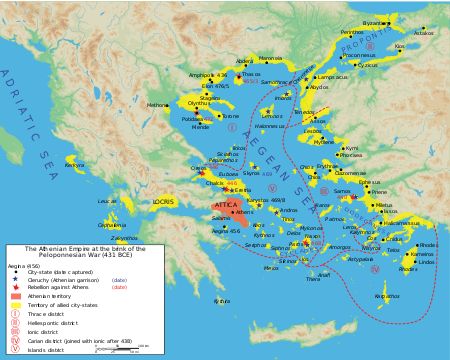

The purpose of the treaty was to prevent another outbreak of war. Ultimately, the peace treaty failed in achieving its goal, with the outbreak of the Second Peloponnesian War in 431 BCE.

Athens was forced to give up all possessions in the Peloponnese, which included the Megarian ports of Nisaea and Pagae with Troezen and Achaea in Argolis, but the Spartans agreed to allow the Athenians to keep Naupactus.[1] It also ruled out armed conflict between Sparta and Athens if at least one of the two wanted arbitration. Neutral poleis could join either side, Sparta or Athens, which implies that there was a formalized list of allies for each side.[2] Athens and Sparta would keep all other territories pending arbitration. It also recognised both Leagues as legitimate, a boost for Athens and its newly-formed empire in the Aegean.

The Thirty Years' Peace, however, lasted only fifteen years and ended after the Spartans had declared war on the Athenians. During the peace, the Athenians took steps in undermining the truce by participating in the dispute over Epidamnus and Corcyra in 435 BC, which angered the Corinthians, who were allies of Sparta. Athens put into effect trade sanctions against the Spartan ally Megara for participating in the Corinthian-Corcyran dispute. In 432, Athens attacked Potidaea, which was a listed ally but a Corinthian colony. The disputes prompted the Spartans to declare that the Athenians had violated the treaty. Sparta declared war, the Thirty Years' Peace was void and the Second Peloponnesian War began.

The Samian Rebellion

The Thirty Years' Peace was first tested in 440 BC, when Athens's powerful ally, Samos, rebelled from its alliance with Athens. The rebels quickly secured the support of a Persian satrap, and Athens found itself faced the prospect of revolts throughout its empire. If the Spartans intervened at that moment, they would be able to crush the Athenians, who were in a vulnerable situation, but when the Spartans called a convention to discuss whether or not they should go to war, it decided not to go to war. The Corinthians were notable for opposing the war with the Athenians.[3]

Corcyra and Corinth

The war between Corcyra and Corinth caused trouble in the peace and was one of the immediate causes of the end of the Thirty Years Peace and the beginning of the Peloponnesian War. The quarrel was over a small distant land, Epidamnus. Corcyra went to Athens to ask for help. Their argument was that there were three fleets worthy of mention in Greece: the Athenian fleet, the Corcyraean fleet, and the Corinthian fleet. If the Corinthians were to get control of the Corcyraean fleet first, Athens would see two of them become one, and it will have to fight against the Corcyraean and the Peloponnesian fleets at once. If Athens accepted the Corcyraean request to join forces, it would be able to fight the Peloponnesian with the help of the Corcyraean fleet.[4] The Corinthian counterargument was that although the treaty said that any unenrolled cities may join whichever side it likes, the clause wass not meant for those who join one side with the intention of hurting the other.[5]

The Athenian decision was to enter an alliance that was only defensive (epimachia), instead of a both offensive and defensive was unusual (symmachia) and is the first such relationship that is known.[6] The decision led to war with Corinthians.

The Battle of Sybota was one of the battles that spurred out of the conflict. The Athenians were forced to fight the Corinthians, which further hurt the peace.

References

- Bagnall, Nigel. “The Inter-War Years 480-431 BC”;The Peloponnesian War: Athens, Sparta and the Struggle for Greece. New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2006. p. 123

- Kagan, Donald. “The Great Rivalry”; The Peloponnesian War. New York: Viking, 2003. 18.

- Kagan, Donald. “Enter Athens”; The Peloponnesian War. New York: Viking, 2003. p. 23-24.

- Thucydides, and Steven Lattimore. The Peloponnesian War. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub., 1998.

- Thucydides, and Steven Lattimore. The Peloponnesian War. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub., 1998.

- Kagan, Donald. “Enter Athens”; The Peloponnesian War. New York: Viking, 2003. p. 37.