Þiðreks saga

Þiðreks saga af Bern ('the saga of Þiðrekr of Bern', also Þiðrekssaga, Þiðriks saga, Niflunga saga or Vilkina saga, with Anglicisations including Thidreksaga) is an Old Norse chivalric saga centering the character it calls Þiðrekr af Bern, who originated as the historical king Theoderic the Great (454–526), but who attracted a great many unhistorical legends in the Middle Ages. The text is either a translation of a lost Low German prose narrative of Theoderic's life, or a compilation by a Norwegian or Icelandic scholar based on German material. It is a pre-eminent source for a wide range of medieval Germanic legends.

Titles

The name Vilkinasaga was first used in Johan Peringskiöld's Swedish translation of 1715.[1] Peringskiöld named it after Vilkinaland, which the saga says was an old name for Sweden and Götaland.[2]

Origins

The saga contains many narratives found in other medieval tales about Theoderic, but also supplements them with other narratives and provides many additional details. It is not clear how much of the source material might have been orally transmitted and how much the author may have had access to written poems.[3] The preface of the text itself says that it was written according to "tales of German men" and "old German poetry", possibly transmitted by Hanseatic merchants in Bergen.[4] Contrary to the historical reality of Theoderic's life, most of the action of the saga is set in Northern Germany, situating Attila's capital at Susat (Soest in Westphalia) and the battle situated in the medieval German poem Rabenschlacht in Ravenna taking place at the mouth of the Rhine. This is part of a process operative in oral traditions called "localization", connecting events transmitted orally to familiar places, and is one of the reasons that the poems collected by the saga-writer are believed to be Low German in origin.

The prevailing interpretation of an Italian saga milieu was largely questioned by the German philologist Heinz Ritter-Schaumburg, who claims the texts to be based on a historiographical vita of an Eastern Frankish Dietrich with his seat rather in Verona cisalpina (Bonn on the Rhine).[5] Ritter-Schaumburg's theory has been rejected by scholars working in the field.[6]

Contents

At the centre of Þiðreks saga is a complete life of King Þiðrekr of Bern.

It begins by telling of Þiðrekr's grandfather and father, and then tells of Þiðrekr's youth at his father's court, where Hildebrand tutors him and he accomplishes his first heroic deeds. After his father's death, Þiðrekr leads several military campaigns: then he is exiled from his kingdom by his uncle Ermenrik, fleeing to Attila's court. There is an unsuccessful attempt to return to his kingdom, during which Attila's sons and Þiðrekr's brother die. This is followed by Þiðrekr's entanglement in the downfall of the Niflings, after which Þiðrekr successfully returns to Verona and recovers his kingdom. Much later, after the death of both Hildebrand and his wife Herrad, Þiðrekr kills a dragon who had killed King Hernit of Bergara, marrying the widow and becoming king of Bergara. After Attila's death, Þiðrekr becomes king of the Huns as well. The final time he fights an opponent is to avenge the death of Heime (who had become a monk and then sworn loyalty to Þiðrekr once again). After this, he spends all his time hunting. One day, upon seeing a particularly magnificent deer, he jumped out of the bathtub and mounts a gigantic black horse – this is the devil. It rides away with him, and no one knows what happened to him after that, but the Germans believe that he received God and Mary's grace and was saved.

In addition to the life of Þiðrekr, various other heroes' lives are recounted as well in various parts of the story, including Attila, Wayland the Smith (in the section called Velents þáttr smiðs), Sigurd, the Nibelungen, and Walter of Aquitaine. The section recounting Þiðrekr's avenging of Hertnit seems to have resulted from a confusion between Þiðrekr and the similarly named Wolfdietrich.

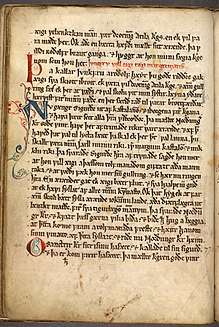

Manuscripts

The principal manuscripts are, with the sigla assigned by Bertelsen:[7]

- Royal Library, Stockholm, Perg. fol. nr. 4 (Mb)

- Copenhagen, Arnamagnæan Institute, AM 178 fol. (A)

- Copenhagen, Arnamagnæan Institute, AM 177 fol. (B)

The Stockholm manuscript is earliest, dating from the late thirteenth century.[8]

Adaptations and influence

Erich von Richthofen in his studies of the Castilian Cantar de los Siete Infantes de Lara has pointed to numerous analogies with the epic of central and northern Europe, in particular stating that in addition to many original Castilian elements and motifs, the epic of the Lara princes has many in common with the Þiðreks saga.[9]

Þiðreks saga was the basis for the Swedish Didrikssagan, a translation from the mid-fifteenth century which survives in one, largely complete, manuscript, Skokloster 115/116.[4][10] The Swedish reworking of the story is rather independent: many repetitions were avoided and the material is structured in a more accessible manner.[4] The Swedish version is believed to have been composed on the orders of king Karl Knutsson, who was interested in literature.[4][1]

Þiðreks saga had considerable influence on Swedish historiography as the saga identified the country of Vilkinaland with Sweden and so its line of kings was added to the Swedish line of kings.[1] In spite of the fact that the early scholar Olaus Petri was critical, these kings were considered to have been historic Swedish kings until fairly recent times.[1] The historicity of the kings of Vilkinaland was further boosted in 1634 when Johannes Bureus discovered the Norwegian parchment that had arrived in Sweden in the 15th century.[1]

Richard Wagner used it as a source for his operatic tetralogy Der Ring des Nibelungen.

Editions and translations of the Norwegian text

.djvu.jpg)

Editions

- Unger, C. R. (ed.), Saga Điðriks konungs af Bern: Fortælling om Kong Thidrik af Bern og hans kæmper, i norsk bearbeidelse fra det trettende aarhundrede efter tydske kilder (Christiania: Feilberg & Landmark, 1853)

- Bertelsen, Henrik (ed.), Þiðriks saga af Bern, Samfund til udgivelse af gammel nordisk litteratur, 34, 2 vols (Copenhagen: Møller, 1905–11): vol. 1

- Guðni Jónsson (ed.), Þiðreks saga af Bern, 2 vols (Reykjavík, 1951) (normalised version of Bertelsen's edition)

Translations

- Die Geschichte Thidreks von Bern (Sammlung Thule Bd. 22). Übertragen von Fine Erichsen. Jena: Diederichs 1924 (German)

- Die Thidrekssaga oder Dietrich von Bern und die Niflungen. Übers. durch Friedrich Heinrich von der Hagen. Mit neuen geographischen Anm. vers. von Heinz Ritter-Schaumburg. St. Goar: Der Leuchter, Otto Reichl Verlag, 1989. 2 Bände (German)

- Die Didriks-Chronik oder die Svava: das Leben König Didriks von Bern und die Niflungen. Erstmals vollst. aus der altschwed. Hs. der Thidrekssaga übers. und mit geographischen Anm. versehen von Heinz Ritter-Schaumburg. – St. Goar : Der Leuchter, 1989, ISBN 3-87667-102-7 (German)

- The Saga of Thidrek of Bern. Translated by Edward R. Haymes. New York: Garland, 1988. ISBN 0-8240-8489-6. Excerpts. (English)

- Saga de Teodorico de Verona. Anónimo del siglo XIII. Introducción, notas y traducción del nórdico antiguo de Mariano González Campo. Prólogo de Luis Alberto de Cuenca. Madrid: La Esfera de los Libros, 2010. ISBN 84-9321-036-6 / ISBN 978-84-932103-6-6 (Spanish)

- Saga de Théodoric de Vérone (Þiðrikssaga af Bern) - Légendes heroiques d'Outre-Rhin. Introduction, traduction du norrois et notes par Claude Lecouteux. Paris: Honoré Champion, 2001. ISBN 2-7453-0373-2 (French)

- Sagan om Didrik af Bern. utgiven av Gunnar Olof Hyltén-Cavallius. Stockholm: Norstedt, 1850-1854 (Swedish)

- Folkvisan om konung Didrik och hans kämpar. Översatt av Oskar Klockhoff. 1900 (Swedish)

- Wilkina saga, eller Historien om konung Thiderich af Bern och hans kämpar; samt Niflunga sagan; innehållandes några göthiska konungars och hieltars forna bedrifter i Ryszland, Polen, Ungern, Italien, Burgundien och Spanien &c.Sive Historia Wilkinensium, Theoderici Veronensis, ac niflungorum; continens regum atq; heroum quorundam gothicorum res gestas, per Russiam, Poloniam, Hungariam, Italiam, Burgundiam, atque Hispaniam, &c. Ex. mss. codicibus lingvæ veteris scandicæ. Översatt av Johan Peringskiöld, Stockholm, 1715 (Swedish and Latin)

Editions and translations of the Swedish text

- The Old Swedish version of Þiðreks saga in the original language

- The Saga of Didrik of Bern, with The Dwarf King Laurin,. Translated (from the Swedish) by Ian Cumpstey. Skadi Press, 2017. ISBN 0-9576-1203-6 (English)

References

- The article Didrikssagan in Nordisk familjebok (1907).

- wilcina land som nw är kalladh swerige oc götaland.

- Davidson, Andrew R., 'The Legends of Þiðreks saga af Bern' (Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Cambridge, 1995).

- The article Didrik av Bern in Nationalencyklopedin (1990).

- Heinz Ritter-Schaumburg, Dietrich von Bern. König zu Bonn. Munich–Berlin 1982.

- See the following negative reviews: Kratz, Henry (1983). "Review: Die Nibelungen zogen nordwärts by Heinz Ritter-Schaumburg". The German Quarterly. 56 (4): 636–638.; Müller, Gernot (1983). "Allerneueste Nibelungische Ketzereien: Zu Heinz Ritter-Schaumburgs Die Nibelungen zogen nordwärts,München 1981". Studia neophilologica. 57 (1): 105–116.; Hoffmann, Werner (1993). "Siegfried 1993. Bemerkungen und Überlegungen zur Forschungsliteratur zu Siegfried im Nibelungenlied aus den Jahren 1978 bis 1992". Mediaevistik. 6: 121–151. JSTOR 42583993. Here 125-128.

- Henrik Bertelsen, Om Didrik af Berns sagas, oprindelige skikkelse, omarbejdelse og handskrifter (Copenhagen: Rømer, 1902), p. 1.

- Helgi Þorláksson, 'The Fantastic Fourteenth Century', in The Fantastic in Old Norse/Icelandic Literature; Sagas and the British Isles: Preprint Papers of the Thirteenth International Saga Conference, Durham and York, 6th–12th August, 2006, ed. by John McKinnell, David Ashurst and Donata Kick (Durham: Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, Durham University, 2006), http://www.dur.ac.uk/medieval.www/sagaconf/sagapps.htm.

- Richthofen, Erich von (1990). "Interdependencia épico-medieval: dos tangentes góticas" [Epic-Medieval interdependence: two Gothic tangents]. Dicenda: Estudios de lengua y literatura españolas (in Spanish). Universidad Complutense (9): 179. ISSN 0212-2952. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- The Saga of Didrik of Bern with the Dwarf King Laurin, trans. by Ian Cumpstey (Cumbria: Skadi Press, 2017), p. 295.

Further reading

- Krappe, Alexander Haggerty. "A FOLK-TALE MOTIF IN THE ÞIĐREKS SAGA." Scandinavian Studies and Notes 7, no. 9 (1923): 265-69. www.jstor.org/stable/40915133.

External links

- F.E. Sandbach, The Heroic Saga-Cycle of Dietrich of Bern. David Nutt, Publisher, Sign of the Phœnix, Long Acre, London. 1906