Theses on the Philosophy of History

"Theses on the Philosophy of History" or "On the Concept of History" (German: Über den Begriff der Geschichte) is an essay written in early 1940 by German philosopher and critic Walter Benjamin. It is one of Benjamin's best-known, and most controversial works.[1]

Composed of twenty numbered paragraphs, Benjamin wrote the brief essay shortly before attempting to escape from Vichy France, where French collaborationist government officials were handing over Jewish refugees like Benjamin to the Nazi Gestapo. Theses is the last major work Benjamin completed before fleeing to Spain where, fearing Nazi capture, he committed suicide in September 1940.

Summary

In the essay, Benjamin uses poetic and scientific analogies to present a critique of historicism.

One interpretation of Benjamin in Thesis I is that Benjamin is suggesting that despite Karl Marx's claims to scientific objectivity, historical materialism is actually a quasi-religious fraud. Benjamin uses The Turk, a famous chess-playing device of the 18th century, as an analogy for historical materialism. Presented as an automaton that could defeat skilled chess players, The Turk actually concealed a human (allegedly a dwarf) who controlled the machine. He wrote:

- One can envision a corresponding object to [The Turk] in philosophy. The puppet called “historical materialism” is always supposed to win. It can do this with no further ado against any opponent, so long as it employs the services of theology, which as everyone knows is small and ugly and must be kept out of sight.

However, the Marxist author Michael Löwy points out that Benjamin puts quotation marks around 'historical materialism' in this paragraph:

- The use of quotation marks and the way this is phrased suggest that this automaton is not 'true' historical materialism, but something that is given that name. By whom, we ask. And the answer must be the chief spokesmen of Marxism in his period, that is to say the ideologues of the Second and Third Internationals."[2]

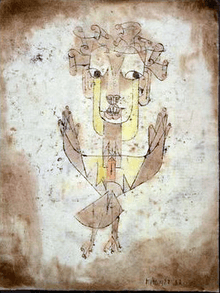

One key to Benjamin’s critique of historicism is his rejection of the past as a continuum of progress. This is most apparent in thesis XI. His alternate vision of the past and “progress” is best represented by thesis IX, which employs Paul Klee’s painting Angelus Novus (1920) as the "angel of history," with his back turned to the future: "Where we see the appearance of a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe, which unceasingly piles rubble on top of rubble and hurls it before his feet [...] That which we call progress, is this storm." Benjamin thus inverts Marxist historical materialism, which was concerned with predicting a revolutionary future, to assert that historical materialism's true task ought to be, in the words of political scientist Ronald Beiner, "to save the past."[3]

According to Benjamin, "Historicism depicts the 'eternal' picture of the past; the historical materialist, an experience with it, which stands alone" (Thesis XVI). Benjamin argues against the idea of an "eternal picture" of history and prefers the idea of history as a self-standing experience. Thus, Benjamin states “To articulate the past historically does not mean to recognize it ‘the way it really was.' It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger" (Thesis VI).

In Thesis XVIII, he highlights a scientific perspective of time only to follow it up with some provocative metaphors:

- 'In relation to the history of organic life on Earth,' notes a recent biologist, 'the miserable fifty millennia of homo sapiens represents something like the last two seconds of a twenty-four hour day. The entire history of civilized humanity would, on this scale, take up only one fifth of the last second of the last hour.' The here-and-now, which as the model of messianic time summarizes the entire history of humanity into a monstrous abbreviation, coincides to a hair with the figure, which the history of humanity makes in the universe.

Benjamin's colleague Gershom Scholem, who is quoted in Theses, believed that Benjamin's critique of historical materialism was so final that, as Mark Lilla would write, "nothing remains of historical materialism [...] but the term itself.[1][4]

Historical context

Scholem,[3] who is quoted in Theses, suggested that the cryptic essay's seemingly definitive rejection of Marxist historical materialism in favor of a return to the theology and metaphysics of Benjamin's earlier writings came after Benjamin recovered from the deep shock he felt following the 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact when the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, previously bitter rivals, announced a non-aggression pact.

Publication history

Benjamin mailed a copy of the essay to the philosopher Hannah Arendt, who passed it on to Theodor Adorno. Benjamin asked that the essay not be published,[1] but it was first printed in a mimeographed booklet entitled Walter Benjamin zum Gedächtnis (In memory of Walter Benjamin). In 1947, a French translation ("Sur le concept d'histoire") by Pierre Missac appeared in the journal, Les Temps Modernes no. 25. An English translation by Harry Zohn is included in the collection of essays by Benjamin, Illuminations, edited by Arendt (1968).[5]

References

- Lilla, Mark (May 25, 1995). "The Riddle of Walter Benjamin". The New York Review of Books.

- Löwy, Michael (2005). Fire Alarm: Reading Walter Benjamin's 'On the Concept of History'. New York: Verso. p. 25. ISBN 1-84467-040-6. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- Beiner, Ronald (1984). "Walter Benjamin's Philosophy of History" (PDF). Political Theory. 12 (3): 423–434. JSTOR 191516.

- Jeffries, Stuart (July 8, 2001). "Did Stalin's killers liquidate Walter Benjamin?". The Guardian. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- "Walter Benjamin - Biography". European Graduate School EGS. Archived from the original on September 7, 2011.