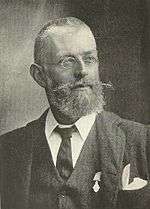

Theodore Leighton Pennell

Theodore Leighton Pennell (1867–1912), was an English Protestant missionary and doctor who lived among the tribes of Afghanistan. He founded Pennell High School and a missionary hospital in Bannu in the North-West Frontier of British India, now Pakistan. For his work he received the Kaisar-i-Hind Medal for public service in India. He published a work on his life under the title Among the wild tribes of the Afghan frontier in 1908. Pennell House at Eastbourne College was named after him.

Early years and 1890s

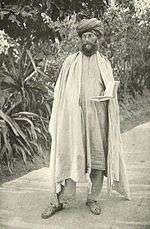

Born in England in 1867, Theodore Pennell was educated at Eastbourne College and qualified as a doctor (MB, MRCS, LRCP) in 1890, completing his MD and FRCS in 1891. He offered his services to the Church Missionary Society (CMS) in 1890. His father had died during his childhood, so he developed a very close relationship with his mother. When CMS sent Pennell to India, his mother decided to go too, and they both began learning Urdu. They reached Karachi in 1892 and went to Dera Ismail Khan, where Pennell began medical work. He often traveled round the villages, wearing Pathan dress and living with the people. He made his first visit to Tank in 1893 and established relationships with the Masud and Wazir tribes.

In October 1893 he moved to Bannu to present the gospel to travelers to and from Afghanistan. He was fluent in Urdu and Pushtu by then. He combined medical work with public preaching in Pushtu and selling Christian literature, in Bannu and the surrounding villages, accompanied by the first Christian in Bannu, Jahan Khan. The mullahs strongly opposed his work, warning people not to accept his medicine. The mullahs tried to drive people away by telling them that the medicines contained alcohol and pig’s blood, and would turn them forcibly into Christians. They also said that if the people were fated to die, then it would be better to die as believers.

Pennell built a small hospital at Bannu with his mother’s money. In 1895 he opened a mission boarding school. Several Muslim inquirers showed an interest in baptism, but faced great opposition from relatives and other Muslims. Among his converts were Tayib Khan and Sayyid Badshah. Sayyid Badshah was shot dead soon after making his profession of faith. In 1896, Pennell was invited to visit the bandit Chakki. Pennell shared the gospel with him to such an effect that soon afterwards Chakki left his banditry; he wrote to Pennell: "I constantly meditate on your words and I have given up killing and robbery."

In 1897 Pennell bought a printing press from Lahore and began publishing a newspaper. There was fighting between the British and the Wazirs but Pennell refused to have an armed guard. "Our best defence is our loving relationship with the tribes," he said. "Rifles and other weapons cannot protect us." In 1898 Pennell passed his Persian exams and began studying Arabic. He preached regularly in Bannu bazaar, despite opposition. Once an Afghan bit his finger, but in court Pennell pleaded for the Afghan’s release. Later three Afghans became Christians.

Twentieth century

In 1901 Pennell began learning Punjabi. In 1903 his disciple, Jahan Khan, went as the first Afghan foreign missionary to the Gulf and East Africa (Mombasa). During 1904 Pennell traveled through the Punjab by bicycle, mixing with the local people, with one Afghan companion. He dressed as a sadhu, and was often penniless. He was amazed at the missionaries’ bungalows, more like forts than houses, separating them from the local people, where they sat waiting for inquirers to come to them rather than going out to sit with the people. He was disappointed at the low level of conduct of most Chuhra and Chamar (Untouchable) Christians who had been baptised without inadequate instruction.

As I travelled, I sometimes rejoiced and sometimes was saddened. I rejoiced that in almost every village and bustee I would meet a Christian, and saddened that that so many of them did not smell like Christians. The missions have the custom of baptising Chuhras and Chamars, and changing their names without examining them, with the result that their misdoings are a blot on the Christian religion.

Pennell was also afraid that concentrating on the Chuhras would deter high caste Hindus and Muslims from coming to Christ. He felt that pressure to produce results in terms of numbers of baptismal candidates was leading to superficial evangelism and slipshod practices, although he acknowledged that many of the Chuhra Christians were worthy spiritual leaders. He was afraid that many so-called Christian workers were "rice Christians", working for the mission for money alone.

In 1908 Pennell became very ill and had to return to England, the first time in 16 years. While there, his mother died. On his return to India he got engaged and married to a Parsee doctor, Alice Sorabji in 1908.[1] and they had a son.[2]

Illnesses and death

In 1909 Pennell was again seriously ill in Bannu and on his recovery, he was showered with flowers and congratulations by the local people. On 15 March 1912, a very sick patient was admitted to Bannu hospital with a dangerous infectious illness. Pennell’s colleague Dr. William Hal Barnett operated on him, and fell sick himself. Pennell operated on Barnett and he too fell sick. Within a few days, Dr. Barnett died and two days later Pennell also died, conscious to the end and unafraid of death. He died at the age of 45 in 1912, from septicaemia leaving his widow.[3] His wife died in 1951, aged 76 years, in Findon, Sussex.[4]

Books and articles about Theodore Leighton Pennell

- Harris, Nigel (2015). Footnotes to History: The Personal Realm of John Wilson Croker, Secretary to the Admiralty (1809-1830), a "Group Family", Chapter 6, Rio and the Afghan Frontier, ISBN 978-1-84519-746-9. Sussex Academic Press, Brighton & Eastbourne.

References

- "Marriages" The Lancet (November 14, 1908): 1495.

- C. L. Innes, Lynn Innes, A History of Black and Asian Writing in Britain, 1700-2000 (Cambridge University Press 2002): 283. ISBN 9780521643276

- "Dr. Pennell, of India" The Missionary Review (June 1912): 475.

- "Deaths" British Medical Journal (March 17, 1951): 597.

Barkat Ullah. Saleeb kay Alambardar (Pioneer Missionaries of the Punjab). Punjab Religious Book Society, Lahore 1957.

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Theodore Leighton Pennell |