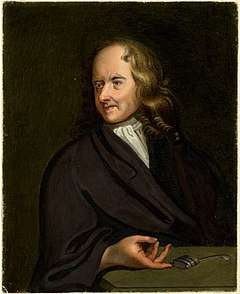

Theodore Haak

Theodore Haak (1605 in Neuhausen – 1690 in London) was a German Calvinist scholar, resident in England in later life. Haak's communications abilities and interests in the new science provided the backdrop for convening the "1645 Group", a precursor of the Royal Society.[1]

Although not himself known as a natural philosopher, Haak's engagement with others facilitated the expansion and diffusion of the “new science” throughout Europe. Haak's language skills were used in translation and interpretation and his personal correspondence with the natural philosophers and theologians of the day, including Marin Mersenne and Johann Amos Comenius; he facilitated introductions and further collaborations. Beginning in 1645 he worked as a translator on the Dutch Annotations Upon the Whole Bible (1657).[2][3][4] The first German translation of John Milton's Paradise Lost is perhaps his best known single work.

Early life and background

Haak was born on 25 July 1605 in Neuhausen in Germany's Palatinate region. Very little is known about Haak's father—Theodore, Sr., who came to study at the University of Heidelberg from Neuburg in Thuringia. It is unclear whether he finished his studies, but he did marry the rector's daughter, Maria Tossanus and from there moved on to an administrative post in Neuhausen.

Haak's mother, Maria Tossanus, descended from three of the Palatinate's most distinguished and intellectual families—Tossanus (Toussaint), Spanheim, and Schloer. Maria's father was the pastor Daniel Toussaint, a French Huguenot exile from Orléans in Heidelberg, who had left France after the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre in 1572. He assumed the chair of theology at Heidelberg in 1586 and became rector in 1594. Young Theodore Haak's relatives included Friedrich Spanheim (1600–1649), professor of theology at Geneva and Leyden; Ezechiel Spanheim (1629–1710), counselor and ambassador for the Elector Karl Ludwig; Friedrich Spanheim (1632–1701), a professor of theology at Heidelberg; and Dr. J. F. Schloer who together with his son Christian also occupied high positions in the Palatinate court.

Definitive documentation regarding Theodore Haak's early life is not extant, but it is likely given his family's intellectual tradition and positions within the university that Haak followed the family's scholarly footsteps. It is likely that he attended the Neuhausen Gymnasium, where his mother's cousin was a teacher and eventually co-rector. He very likely would have matriculated at the University of Heidelberg had it not been for the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), which devastated the Palatinate area and Heidelberg in particular. The University of Heidelberg essentially closed and did not reopen again until the Peace of Westphalia (1648).[5]

Traveller

In 1625, at the age of twenty, Haak embarked for England where he visited Oxford and Cambridge Universities. A year later he returned to Germany and spent the next two years in Cologne, where he regularly met in secret with other Protestants for religious gatherings. He brought back from England a copy of Daniel Dyke's Mystery of Self-Deceiving, which he shared with his Protestant spiritual circle. This volume was also Haak's first work in English to German translation, completed in 1638 under the title Nosce Teipsum: Das Grosse Geheimnis dess Selbs-betrugs.

In 1628 Haak returned to England and spent the following three years at Oxford, but left in 1631 without a degree. Shortly after, he was ordained a deacon by the Bishop of Exeter but never took full orders. He lived for a short time in Dorchester but by 1632 left the countryside for London with the intention to return to Germany. His plans, however, were interrupted when he received a letter from the exiled ministers of the Lower Palatinate seeking his assistance with raising funds and influencing English Protestant clergymen in their cause. It was Haak's Calvinist heritage, language abilities, and presence in London that brought him to the attention of the Palatinate's ministers. When this task was completed, Haak returned to Heidelberg in 1633; but, with war still ravaging Germany, Haak again, left this time for Holland. In 1638 at the age of thirty-three, Haak enrolled at the University of Leyden, where many of his relatives had already studied.[6]

Role in knowledge networks

By this time, Haak was becoming well known as a gentleman-scholar with independent means and excellent family connections. In 1634, Haak had formed an advantageous and lifelong relationship with Samuel Hartlib, a fellow German expatriate in London. Since 1636 Hartlib had been in frequent correspondence with Johann Amos Comenius, who forwarded to Hartlib his manuscript, De Pansophia. In 1638 when Haak returned to England, he found his friend Hartlib engaged, intellectually and logistically, with Comenius and another Calvinist intellectual, John Dury (1596–1680).

Hartlib was a polymathic intelligencer, and the "Hartlib circle" reached into Holland, Transylvania, Germany, England, and Sweden. France, however, was an obvious gap in his European network and Haak's French language abilities drew him to Hartlib, who knew that an informal philosophical group existed in Paris. Its intelligencer was Marin Mersenne, a French theologian, mathematician, philosopher, and friend of Thomas Hobbes, René Descartes, and Blaise Pascal.

Haak initiated a correspondence with Mersenne in 1639, likely at the request of Hartlib. His initial letter enclosed mathematical studies by John Pell and works by Comenius. Mersenne replied almost immediately and although he briefly commented on Pell and Comenius, it was his request to Haak to send further scientific information that sustained their corresponding relationship.[7] The correspondence between Haak and Mersenne covered current scientific and mechanical subjects such as tides, the making of telescopes, spherical glasses, new planetary discoveries, magnets, cycloids, mills, and other machines. The nature of the correspondence was somewhat of a disappointment to Hartlib, who was more interested in expanding Comenius's pansophic work. Mersenne showed greater interest in English scientific experiments and results, and the correspondence between Mersenne and Haak did serv to connect a small group of interested philosopher-scientists in London to Mersenne's scientific group in Paris.[8][9] [10]

The “1645 Group” and the Royal Society

Haak's correspondence with Mersenne dwindled after 1640; Haak had diplomatic engagements in Denmark, and had started on his more ambitious translation work, including an English translation of the Dutch Annotations upon the Whole Bible, to which he was commissioned by The Westminster Assembly 1645. In 1647, his correspondence with Mersenne resumed. Scientifically-minded men began to meet in London beginning in 1645. This "1645 Group", or as it later was and misleadingly known—the 'Invisible College'—is considered by some a predecessor of the Royal Society.[11] The group's meetings and philosophical interests afforded Haak the perfect opportunity to re-engage with his French friend. Letters in 1647 indicate that Haak was writing on behalf of the group, to ask Mersenne about developments in France, and requesting an exchange of knowledge, even asking for a report when others from the Paris group returned from their scientific travels.

Haak's involvement the group then seems to have waned. As it re-emerged after the Restoration, it became more formalized within the Royal Society. One year after the founding of the Society, Haak was formally entered as a member in 1661 and in fact is listed as one of the 119 original fellows.

Haak's work with the Royal Society was similar to the work that had so far engaged him throughout his life—translation, correspondence, and diffuser of knowledge. One of the first tasks he undertook was a translation of an Italian work on dyeing. He also acted as an intermediary on behalf of his old friend Pell, and communicated to the Society Pell's studies, including observations of a solar eclipse. Later it was to respond to university professors and civil administrators seeking information on the work undertaken by the Society. Other minor works prepared for the Society included a history of sugar refining and some German translations.

His massive work in translating the Statenvertaling met Kantekeningen into English was published in London by Henry Hill 1657.

Haak died on 9 May 1690, at the home of Frederick Slare, a friend, cousin and F.R.S., in the Fetter Lane area of London.[12] His life is "a study of the seventeenth century world in all its complexities of politics, new scientific discoveries, and intellectual strivings" both in England and abroad.[13] His networks evidence the "formal and informal institutional arrangements, and social relationships" that were key to developing "the new philosophy" during the Scientific Revolution.[14]

Works by Theodore Haak[15]

- Dyke, Daniel. Mystery of Self-Deceiving, [Nosce Teipsum: Das grosse Geheimnis dess Selb-betrugs, (Basel, 1638)]. Translated from English into German.

- _____. A Treatise of Repentance [Nützliche Betrachtung der wahren Busse (Frankfurt, 1643)]. Translated from English into German

- Milton, John. Paradise Lost [Das Verlustige Paradeiss, unpublished] Translated from English into German.

- Schloer, Frederick. Sermon on the Death of the Two Renowned Kings of Sweden and Bohemia Publicly Lamented in a Sermon, (London, 1633). Translated from the German into English

- Solemn League and Covenant. Translated from English into German

- The Dutch Annotations Upon the Whole Bible. Translated from Dutch into English. (London, 1657).

References

- Pamela Barnett, Theodore Haak, F.R.S. (1605-1690) (The Hague: Mouton, 1962)

- Dorothy Stimson, Hartlib, Haak and Oldenburg: Intelligencers, Isis, Vol. 31, No. 2 (Apr., 1940), pp. 309–326

Notes

- . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- Biblical Criticism Catalogue Number 72

- "Turpin Library - Rare Books Collection". rarebooks.dts.edu. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- "Turpin Library - Rare Books Collection". rarebooks.dts.edu. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- Pamela Barnett, Theodore Haak, F.R.S. (1605-1690) (The Hague: Mouton, 1962), 9-12.

- Barnett, pp. 13-26.

- Barnett, pp. 32-38.

- R. H. Syfret, “The Origins of the Royal Society,” Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 5, no. 2 (April 1, 1948): 131.

- J. T. Young (1998), Faith, Alchemy and Natural Philosophy: Johann Moriaen, Reformed Intelligencer, and the Hartlib Circle, p.12.

- Lisa Jardine, On a Grander Scale (2002), p. 66.

- Pamela Barnett, Theodore Haak and the early years of the Royal Society, Annals of Science, Volume 13, Number 4, December 1957, pp. 205-218(14)

- Stephen, Leslie; Lee, Sidney, eds. (1890). . Dictionary of National Biography. 23. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Barnett, Theodore Haak, F.R.S. (1605-1690), 159.

- David Lux and Harold Cook, “Closed Circles or Open Networks?: Communicating at a Distance During the Scientific Revolution,” Hist Sci 36 (1998): 180.

- Barnett, Theodore Haak, F.R.S. (1605-1690), App. 2.