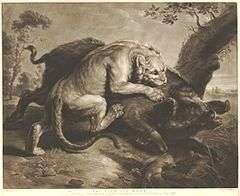

The lion, the boar and the vultures

The lion, the boar and the vultures is sometimes counted among Aesop’s Fables and warns against quarrels of which others will take advantage. It is numbered 338 in the Perry Index.[1]

One man’s loss is another man’s gain

The fable only existed in Greek sources formerly and concerns a lion and boar who fight each other to be the first to drink from a spring. Observing vultures gathering to swoop on the loser, the two fierce animals decide that it is better to have friendly relations rather than be eaten by such vile creatures. The story appeared in few of the main fable collections but was given popularity during the Renaissance by being included among the emblems of Andrea Alciato under the heading “One man’s loss is another man’s gain” (ex damno alterius, alterius utilitas). The Latin quatrain accompanying the illustration does not mention the cause of the quarrel but concludes that the victor’s glory will belong to the one that gets the spoil.[2]

Still another moral was given the story by Arthur Golding in his manuscript A Moral Fabletalk later in the 16th century. There the religious author, observing the behaviour of the waiting vulture, concluded that hope is often deceived and should only be placed in God.[3] A century later, at the end of several civil conflicts, Roger L'Estrange’s reflection was ultimately sceptical: “There are several sorts of men in the world that live upon the sins and the misfortunes of other people…for the wrangling of some is the livelihood of others.” He lists those who gain as lawyers, religious divines and soldiers.[4] In the 18th century William Somervile adapted the theme of the profits of combat going to others, giving it the contemporary context of bear-baiting in his fable of “The Dog and the Bear”. There Towser and Ursin agree to desist in mid-combat, since only their masters gain in the end.[5]

Aesop’s original fable was made the subject of a painting by Frans Snyders which in the 18th century entered the collection of the dukes of Newcastle. Robert Earlom (1743-1822) made a mezzotint engraving of this in 1772, of which there are both hand-coloured [6] and plain versions.[7] In 1811 Samuel Howitt’s independent treatment of the subject featured vultures circling above the combatants.[8] The plate was also bound into Howitt’s A New Work of Animals, where it was accompanied by L'Estrange’s version of the fable.[9] A new translation was published in 1867 by George Fyler Townsend, for which the illustrator was Harrison Weir.[10]

References

- Aesopica

- Emblem 124

- Arthur Golding’s "A Moral Fabletalk" and Other Renaissance Fable Translations, MHRA 2017, p.244

- Fables of Æsop And Other Eminent Mythologists, 1692, p.428

- Robert Anderson, The Poets of Great Britain, London 1794, Vol.8, p.514

- Donald Heald com

- British Museum

- Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America

- p.11 (34)

- Aesopica