The Wolf and the Shepherds

The Wolf and the Shepherds is ascribed to Aesop’s Fables and is numbered 453 in the Perry Index. Although related very briefly in the oldest source, some later authors have drawn it out at great length and moralised that perceptions differ according to circumstances.

The fable

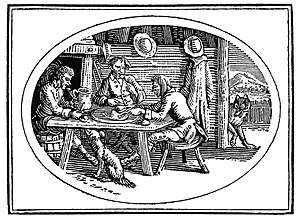

The fable is told very briefly by Aesop in Plutarch’s The Banquet of the Seven Sages: “A wolf seeing some shepherds in a shelter eating a sheep, came near to them and said, 'What an uproar you would make if I were doing that!'"[1] Jean de la Fontaine based a long fable on the theme in which the wolf is close to repentance for its violent life until it comes upon the feasting shepherds and reflects on human hypocrisy (X.5).[2] The Scottish poet James Beattie wrote an even longer verse account in 1766, observing that, in the case of lawmakers, might overweighs equity. This point is underlined when the wolf has to run for his life after his debate with the shepherds is cut short by having the dogs set on him.[3]

There were also shorter versions of the fable which returned to the brevity of Plutarch. He is quoted directly in the editions of the fable illustrated by Thomas Bewick , prefaced only with the remark "How apt are men to condemn in others what they practise themselves without scruple."[4] George Fyler Townsend dispensed even with that in his new translation of the fables, published in 1867.[5] And in Russia Ivan Krylov’s early 19th-century verse retelling is limited to eight lines,[6] as against La Fontaine’s 41 and Beattie’s 114.

In 1490 the neo-Latin poet Laurentius Abstemius wrote a lengthy Latin imitation of the fable in which different characters were involved in a similar situation. There a fox on the prowl comes across farm women feasting on roast chicken and says that it would have been different if he had dared to act in the same way. But he is answered that there is a difference between theft and disposing of one’s own property.[7] Roger L'Estrange included a racy version of the story in his fable collection of 1692, drawing the moral that situations alter circumstances.[8]

References

- 13.156a

- Elizur Wright’s translation

- “The wolf and the shepherds”, Miscellaneous Poems, pp.166-70

- Fable 31

- Fable 115

- Kriloff’s Original Fables, trans. Henry Harrison, London 1883, p.210

- Hecatomythium Fable 9, De vulpe et mulieribus gallinam edentibus

- ”A Fox and a Knot of Gossips”, Fable 263