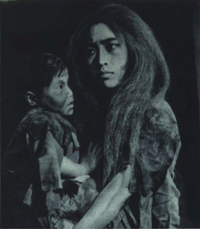

The White Haired Girl

The White-Haired Girl (Chinese: 白毛女; pinyin: Bái Máo Nǚ) is a Chinese opera, ballet, (later adapted to Beijing Opera and a film) by Yan Jinxuan to a Chinese libretto by He Jingzhi and Ding Yi. The folklore of the white-haired girl is believed to have spread widely in the areas occupied by the Communist Party of Northern China since the late 1930s. Many years later, a literary work was created in the liberated area controlled by the Communist Party of China in the late 1940s. The film was made in 1950 and the first Peking opera performance was in 1958. The first ballet performance was by Shanghai Dance Academy, Shanghai in 1965. It has also been performed by the noted soprano Guo Lanying.

The opera is based on legends circulating in the border region of Shanxi, Chahar and Hebei, describing the misery suffered by local peasantry, particularly the misery of the female members. The stories are based on real-life stories of no less than half a dozen women, in a time frame stretching from the late Qing Dynasty to the 1920s or 1930s. The political overtone and historical background when it was created means that communist propaganda was added in inevitably, and the most obvious example was the added portion of happy ending and the protagonists joining the communist force, which did not happen in real life.

Along with Red Detachment of Women, the ballet is regarded as one of the classics of revolutionary China, and its music is familiar to almost everyone who grew up during the 1960s. It is one of the Eight Model Operas approved by Jiang Qing during the Cultural Revolution.The White-Haired Girl also intentionally showed the political meaning by creating a figure of diligent and beautiful country woman who was under the oppression of the evil landowner. As it aroused an emotion to against the “old ruling class”, it satisfied “moral ideas of the left-wing literary and artistic intelligence, the popular social and cultural values of rural and urban audiences”. The film presented “the traditional Chinese agricultural lifecycle”, which the poor lived in poverty no matter how hard they have trying. It implied a revolution to overthrown the unchanging social structure. As the mise-en-scene of the film, it used fair amount of medium-shot to curve the character through facial expressions.

Plot

(Based on the ballet version)

It is the eve of the Chinese Spring Festival. The peasant girl Xi'er from a village in Yanggezhuang, Hebei province is waiting for her father Yang Bailao to return home to celebrate the Spring Festival together. Her father, a tenant peasant hired under the despotic and usurious landlord Huang Shiren (who makes a fortune as a loan shark exploiting peasants), has been force to run away from home to avoid the debt collectors. Xi'er's girl friends come to bring her paper cuttings with which they decorate the windows. After the girls leave, Xi'er's fiancé, Wang Dachun, comes to give two catties of wheat flour to Xi'er so that she can make jiaozis. In turn, Xi'er gives Dachun a new sickle as a gift.

Xi'er's father secretly returns home at dusk, with no gift other than a red ribbon to tie to his daughter's hair for the festivity of the holiday. The landlord catches wind of his return and will not let them have a peaceful and happy Spring Festival, and the debt collector comes for the high rent which Yang has been unable to pay. They kill Yang Bailao, and take away Xi'er by force as his concubine. Dachun and other villagers come on the scene, and Dachun wants to go to the landlord's residence to fight for justice but is stopped by Zhao Dashu (Uncle Zhao) who, instead, instruct Dachun and other young people to join the Eighth Route Army.

At the home of the landlord, Xi'er is forced to work day and night as a slave and is exhausted. Zhang Ershen (literally Second Aunt Zhang), an elderly maid of the landlord, is very sympathetic of Xi'er. Xi'er dozes off while trying to take a short break. The mother of the landlord comes on the scene and, with her hairpin, pokes Xi'er's face to wake her up. The landlord mother then orders Xi'er to prepare her a lotus seed soup. When the soup is served, the landlord mother, displeased with the taste, pours the still-boiling soup on Xi'er's face. Outraged by the pain and anger, Xi'er picks up the whip that the landlord uses to punish her, and beats up the landlord mother. The landlord mother falls and crawls on the floor attempting to flee while Xi'er continues to whip her with her utmost strength. Xi'er gets her vengeance, but she is subsequently locked up by the landlord.

One day, the landlord leaves his overcoat in the living room and in the pocket of the overcoat is the key to Xi'er's cell. Zhang Ershen is determined to help Xi'er. She takes the key and opens the door for Xi'er, who flees. Shortly, the landlord finds Xi'er missing, and sends his accomplice, Mu Renzhi, and other men to chase her. Xi'er comes to a river that stops her. She takes off a shoe and leaves it at the river side, and then hides in the bush. Mu Renzhi and his men find the shoe and assume that Xi'er has drowned herself in the river, and they report to the landlord as such.

Xi'er escapes to the mountains, and in the following years, she lives in a cave, gathers offerings for food from a nearby temple. She fights attacking wolves and other beasts. In time, her hair turns white from suffering the elements.

On one stormy night, the landlord Huang Shiren and several of his other servants come to the temple to worship and provide offerings. Their trip is stopped by the thunderstorm. Coincidentally Xi'er is now in the temple too, and by the light of a flash of lightning, the landlord sees her — with her long white hair and shabby clothes that have been weathered to nearly white. He thinks it is the reincarnation of a goddess who has come to punish him for his mistreatment of Xi'er and other despotisms. He is so frightened that he is literally paralyzed. Xi'er recognizes that it is her arch-enemy and seizes the opportunity to take further revenge. She picks up the brass incense burner and hurls it against the landlord. The landlord and his gang flee.

Meanwhile, her fiancé, Wang Dachun, has joined the Eighth Route Army and fought the Japanese invaders. Now he returns with his army to overthrow the rule of the imperialist Japanese and the landlord. They distribute his farmland to the peasants. Zhang Ershen tells the story of Xi'er, and they decide to look for her in the mountains. Wang Dachun finally finds her in the cave with her hair turned white. They reunite and rejoice. The final ending of the film fulfilled the audience’s revenge to the “evil landlord”. The landlord accepted the punishment from the angry people under the fair judgment of the CCP.

History

In 1944, under the direction of President Zhou Yang, some artists of The Lu Xun Academy of Art in Yan 'an produced an opera, “The White Haired Girl”, based on the folk tales and legends of the "white-haired immortal" in 1940.

According to one of its original writers, He Jingzhi, the play "The White-haired girl" is based on a real-life story about a "white-haired goddess" in North Hebei Province in 1940s. The "White-haired goddess" is a peasant woman who lost her family lived in the wild like animals, who was then found by The Eighth Route Army and sent to the village.

To commemorate the Seventh National Congress of the Communist Party of China, the opera was first performed in Yan An in 1945, and was highly praised by the leadership of the Communist Party and achieved great success. Later, it was widely performed in the liberated area. The end of 1945 saw the Shanxi-Chahar-Hebei version. In order to meet the needs of " national salvation to prevail over cultural enlightenment", the play has been continuously adapted into different versions.

In July 1947, Ding Yi, another opera co-author, made many changes and deletions to the Shanxi-Chahar-Hebei version, mainly to cut pregnant Xi Er's hard life after escaping to the cave.

In 1950, the opera was further adapted into a new version by He Jingzhi. This revision followed Ding Yi's thought of deletion and modification, and also made major changes to the original play. These changes included some important parts of Xi Er's characters.

During the Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976, it was further adapted based on Peking Opera, and the ballet model "White Haired Girl" was born. It became one of the few operas performed repeatedly during the Cultural Revolution.

Differences among adaptations

The original hybrid, western-style geju opera was created by collaboration of composer Ma Ke and others in Yan'an's Lu Xun Art Academy in 1945. It differs from later adaptations in its depiction of superstition. In the original opera of 1945, Xi'er was caught by the local population, who believed she was a ghost and had power to inflict harm on people. To try to destroy her evil magical power, the local populace poured the boys' urine, the blood of a slain black dog, menstrual blood, and human and animal feces on her, something that was done in real life to at least one of the girls. Her suffering as a woman in a patriarchal society gradually became the suffering of the exploited and oppressed social class. Communists felt it was necessary to eradicate the superstition that was still deeply rooted in the minds of local populaces, so this barbaric act was accurately reflected in the opera, with Wang Dachun eventually stopping the mob after recognizing Xi'er, leading to the final happy ending. After the communist victory in China, this scene was deleted in later adaptations for fear of encouraging superstition and presenting a negative image of the working-class people.

In the 1950 film version, Xi'er's father was tricked and driven to suicide by Huang Shiren. Xi'er was raped by Huang Shiren and became pregnant. When Huang Shiren got married, he and his mother decided to sell Xi'er to a brothel. With Auntie Yang's help, Xi'er ran away to the mountains and gave birth to a still-born baby. The suffering of Xi'er reflected the contradiction between the poor peasants and the landlord class in the semi-colonial and semi-feudal society, which proved that only the people's revolution led by the Communist Party could remove the feudalism and free the peasants who had the same fate as Xi'er.

Music

"White-haired Girl" is a new national opera that combines poetry, song and dance. First, the structure of the opera plot, the division of the traditional Chinese opera, the scene changes, diverse and flexible. Secondly, the language of opera inherits the fine tradition of singing and singing in Chinese opera. Third, opera music uses northern folk songs and traditional opera music as materials and creates them. It also absorbs some expressions of Western opera music and has a unique national flavor. Fourth, opera performance, learning the traditional Chinese opera performance methods, paying due attention to dance figure and chanting rhythm, at the same time, also learning how to read the lines of the drama, both beautiful and natural, close to life. This play uses the tunes of northern folk music, absorbs drama music, and draws on the creation experience of Western European opera. Unlike other ballets, the music of The White-Haired Girl is more like that of a musical, i.e., it blends a large number of vocal passages, both solos on the part of Xi'er and choruses into the music. Because of their mellifluous melodies, these songs became very popular. The following is a partial list of these songs:

- "Looking at the World"

- "The Blowing North Wind"

- "Tying the Red Ribbon"

- "Suddenly the Day Turns to Night"

- "Join the Eighth Route Army"

- "Longing for the Rising Red Sun in the East"

- "Big Red Dates for the Beloved"

- "The Sun Is Out"

- "Dear Chairman Mao"

External links

- Bai mao nu on IMDb

- The White Haired Girl is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- Youtube: Xi'er's Solo in Act I

- Youtube: The White-Haired Girl (1971, full movie of ballet version)

Citation

Bai, Di. "Feminism in the Revolutionary Model Ballets The White-Haired Girl and The Red Detachment of Women." Art in Turmoil: The Chinese Cultural Revolution 76 (1966): 188-202.

Bohnenkamp, Max L. Turning Ghosts into People: “The White-Haired Girl”, Revolutionary Folklorism and the Politics of Aesthetics in Modern China, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2014.

Jia, Bo. Gender, Women's Liberation, And The Nation-State: A Study of The Chinese Opera The White Haired Girl. New Brunswick, New Jersey. May, 2015.

Ll Jing, The Retrospect and Reflection of the New Yangge Movement's Research[J],Journal of Qinghai Normal University(Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition).Journal of Qinghai Normal University,Xining 810008,China. March, 2009.

Shan Yuan, Analysis of the Implied Connotation of the Text: White Hair Girl[J],Research of Chinese Literature, Xianning Teachers College, Xianning city, Hubei 437005,China. March,2002