The Shield and the Sword (film)

The Shield and the Sword (Russian: Щит и меч, romanized: Shchit i mech) is a 1968 Soviet spy series in four parts directed by Vladimir Basov.[1] It is based on a novel by Vadim Kozhevnikov, who was Secretary of the Soviet Writers' Union.[2] It was a highly influential in the Soviet Union, inspiring many, including Vladimir Putin, to join the KGB.[3]

| The Shield and the Sword | |

|---|---|

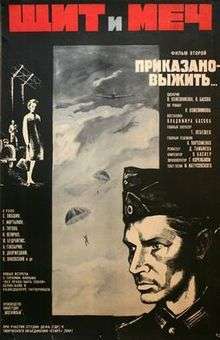

Part 2 poster | |

| Directed by | Vladimir Basov |

| Produced by | Mosfilm |

| Written by | Vladimir Basov Vadim Kozhevnikov |

| Starring | Stanislav Lyubshin Oleg Yankovsky Georgy Martyniuk Vladimir Basov Alla Demidova |

| Music by | Veniamin Basner |

| Cinematography | Sergei Vronsky |

Production company | |

Release date |

|

Running time | 325 min. |

| Country | Soviet Union |

| Language | Russian |

The song What Does Motherland Begin With (С чего начинается Родина), sung by Mark Bernes, that was main musical theme of each film in the series, became well known in the USSR.

Parts

- Part 1. No Right To Be Themselves (Без права быть собой)

- Part 2. The Order is: Survive (Приказано выжить)

- Part 3. Without Appeal (Обжалованию не подлежит)

- Part 4. The Last Frontier (Последний рубеж)

Plot

The year is 1940 and Nazi Germany is at the height of its military power, having captured most of Europe and eyeing the Soviet Union to the East. The Soviet military command suspects hostile intent from Germany and so arranges for its spies to infiltrate ranks of the German military and the SS. Alexander Belov (Lyubshin) is a Russian spy, who travels from Soviet-held Latvia to Nazi Germany under an alias of Volksdeutsche Johann Weiss. His mastery of the German language, steel nerves and an ability to manipulate others help him to use his connections in the SS to ascend the ladder of the Abwehr and then in the SD. He uses his position to identify sympathetic Germans, who help him to procure vital intelligence, and to help local resistance movements in their collective fight against Nazism.

Cast

- Stanislav Lyubshin as Alexander Belov / Johann Weiss

- Oleg Yankovsky as Heinrich Schwarzkopf

- Georgy Martyniuk as Aleksey Zubov / Alois Hagen

- Vladimir Basov as Bruno

- Alla Demidova as Angelika Buecher

- Juozas Budraitis as Dietrich

- Aleksey Glazyrin as Steinglitz

- Valentina Titova as Nina

- Natalia Velichko as Elsa

- Vladimir Balashov as Sonnenberg

- Algimantas Masiulis as Willi Schwarzkopf

- Nikolai Zasukhin as Papke

- Lev Polyakov as Gerlach

- Nikolay Grabbe as Deaf-mute Man

- Yelena Dobronravova as Deaf-mute Woman

- Vatslav Dvorzhetsky as Lansdorf

- Anatoly Kubatsky as Franz

- Nikolay Prokopovich as Schulz

- Kristina Lazar as Brigitte

- Valentin Smirnitsky as Andrey Basalyga

- Igor Bezyayev as Rabbit

- Vsevolod Safonov as Nail

- Vladimir Marenkov as Ace

- German Kachin as Cartilage

- Igor Yasulovich as Goga

- Radner Muratov as Shaman

- Konstantin Tyrtov as Tit

- Sergey Plotnikov as General Baryshev

- Inga Budkevich as Inga

- Uldis Dumpis as Luftwaffe Ace

- Helga Göring as Frau Dietmar

- Horst Preusker as Prof. Stutthoff

- Wojcech Duriasz as Jerzy Czyzewski

- Kurt-Mueller Reizner as Karl Kunert

- Silard Banki as Janos Molnar

- Vladimír Brabec as Jaromir Drobny

- Vladimir Osenev as Hitler

- Vyacheslav Dugin as Himmler

- Mikhail Sidorkin as Göring

Reception

Ben Macintyre, writing in the London Times in February 2020, described the series as "truly bad television, raw Soviet propaganda, alternately clunky and schmaltzy." In the final scene "our wounded spy-hero is reunited with his elderly mother. ... You would need a heart of stone not to laugh at it."[3]

References

- Hake, Sabine (31 August 2012). Screen Nazis: Cinema, History, and Democracy. University of Wisconsin Pres. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-299-28713-9. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- Marsh, Rosalind (2007). Literature, History and Identity in Post-Soviet Russia, 1991-2006. Peter Lang. p. 75. ISBN 978-3-03911-069-8. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- Macintyre (20 February 2020). "Putin's spies are pulp fiction characters". The Times. London. Retrieved 29 February 2020. (subscription required)

External links

- The Shield and the Sword on IMDb

- The Shield and the Sword on DVD for sale through Rare War Films

- Final scene. Weiss-Belov meets his mother in Soviet hospital in May, 1945 on YouTube